Tony-Winning Director Mary Zimmerman on Creating the Guys & Dolls-iest Guys & Dolls

(© Jenny Graham)

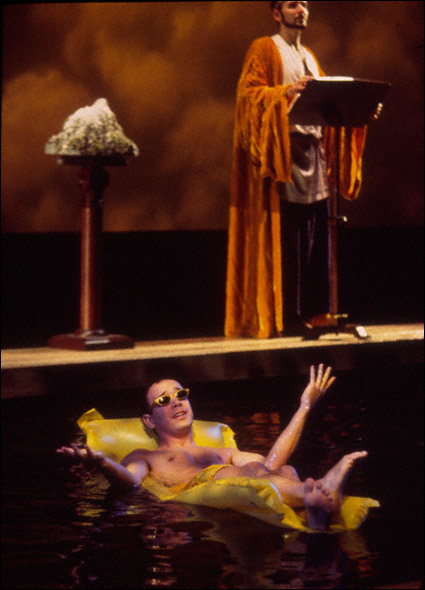

When a theatergoer hears the name Mary Zimmerman, one tends to expect the unexpected. Throughout her career, Zimmerman has developed a style unlike anything ever seen onstage, telling massive stories through beautiful visuals, music, and movement. She adapts classic stories, shaping the texts along the way in rehearsals. She is best known for Metamorphosis, her imaginative adaptation of Ovid's poem. With an actual swimming pool onstage, the production netted Zimmerman a Tony Award for Best Director of a Play, making her the second woman in history to earn the honor.

For her latest project, Zimmerman has turned to something equally unexpected: the Frank Loesser, Abe Burrows, and Jo Swerling musical Guys and Dolls. The musical fable of Broadway, adapted from the stories of Damon Runyon, played a nine-month run in the repertory Oregon Shakespeare Festival from February to November, and has now moved to California. Zimmerman's acclaimed staging of the show is running through December 20 at Beverly Hills' Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts.

So how did one of the world's most admired theatrical auteurs come to direct one of the canon's most acclaimed musical comedies? All Zimmerman had to do was say it.

(© Liz Lauren)

How did you come to direct Guys & Dolls at Oregon Shakespeare Festival?

It's a little bit of a convoluted story, but it's true. I was in the middle of a difficult tech on a difficult show and I kept saying out loud, "I want to do Guys & Dolls." [It's] something that, from the beginning, has a reasonable chance of success, that I'm not writing as I go, that I'm not responsible for every aspect. I was telling this to everyone I was seeing.

About four weeks later, I got an email from [artistic director] Bill Rauch saying, "I have the craziest idea: What would you think about your doing Guys & Dolls?" I immediately said yes. A couple of months went by, and I was telling this story to a couple of actor friends, and they both kind of slid their eyes back and forth like "Should we tell her?" And they said, "We told Bill you were saying that." He's so cunning and canny that he just decided he had a better chance of it actually happening if it seemed like a coincidence.

Was it as easy as you expected or hoped it would be?

[laughs] I think it was easier, but I don't want to be cavalier about it…I'm not that experienced in musicals. So I went in with the regular nervousness and preparation. It's just that you know you've got your hands on something pleasurable to be around, if only for the tunes. It was a fantastic process. After the first few days, I said it was as though this company and I had done Guys & Dolls a couple of years ago and we were just reassembling it. So many of the people are so right in their parts.

(© Jenny Graham)

Are there ways that this show is similar to the material you usually work on?

In one way, it's very far from what I usually do, but in another, it's very close in that it's a masterpiece of the genre. It's a virtuoso piece of entertainment and I want to try and get close to texts that I think are going to teach me something about narrative and storytelling. The way the plot works is so ingenious, and there's nothing unnecessary. It all hinges on the problem of "Where are we going to have the crap game?" That penetrates the plot and the subplot as both of them wheel around the wager.

As an adapter yourself, what is it like working on a piece that itself is an adaptation of Damon Runyon’s stories?

Just as someone who's spent my life adapting, of all the things that might be celebrated about the show, one of them that's not necessarily at the forefront is what a good adaptation it is of the Runyon stories. There's almost no romance in any of those stories, and they bring that front and center. The signature of Damon Runyon is that [the characters] talk about quite prosaic or low-class things, but they do it in a vernacular that has no contractions and a fancy vocabulary that's characteristic of the gangsters of his world. I read an essay somewhere that said that the opening, "Fugue for Tinhorns," musically does that. They're talking about racing sheets, which never comes into play again, and it's done in a very classical, old form. That's an exact analogy to Runyon speak, to have a fancy form against a prosaic subject.

(© Joan Marcus)

What do people say when they hear that you're directing a classic like Guys & Dolls?

They're very surprised. They also say something next which doesn’t really thrill me. They say, sort of, "What are you going to do to it? How are you going to put your stamp on it?" I don't feel like I'm doing anything in a signature way; I feel like I'm doing it the only way I know how. It's just that the kinds of texts I normally do demand ingenious solutions to problems of "How do you fly carpets or trains of camels or have someone turning into a bird or melting into a river?" You have to be inventive. You have to make big moves in things that weren't written for the theater. But this was written for the theater. My entire goal is to make it the Guys & Dolls-iest Guys & Dolls that I can.

(© Jenny Graham)