"We're Next": An Oral History of the Broadway Shutdown, Part 2

Business was booming. Nearly 15 million people had seen Broadway shows during the 2018-19 season. The total box office gross was $1.8 billion. And as the calendar pages flipped to January 2020, every theater had been booked for what was expected to be a prosperous spring, with 21 productions scheduled to open between the first of the year and the late-April Tony Awards cut-off.

By Friday, March 13, that was all moot. The curtain had unceremoniously fallen the afternoon before by order of New York State, as cases of the novel coronavirus ravaged the city and rapidly filled hospitals beyond capacity. There were hundreds of different ways to have seen this eventuality coming — audiences began to thin, whole companies and other theater personnel were getting sick — but Broadway lives by one motto: The show must go on.

The September 11 terrorist attacks kept Broadway closed for a few days. Labor strikes had darkened theaters in the past, but they were generally resolved within weeks. Covid-19 has caused the longest shutdown in the history of the Broadway industry, and while there are glimmers of hope on the horizon in the form of a vaccine, there is still no definitive end in sight.

As we hit the summer of 2020, I started documenting stories from across the Broadway community in an effort to make sense of it all. This is the second in a multi-part oral history of the Broadway industry shutdown, as told by the artists making theater eight times a week. These conversations have been lightly edited for clarity and nothing else, but they all paint a picture that could be a metaphor for the world itself: we were all blissfully naive to impending disaster, until.

Read each part here as they become available every Monday.

(© Tricia Baron)

In This Section

John Raymond Barker, stage door attendant

Tricia Baron, freelance photographer for TheaterMania

Joe DiPietro, librettist of Diana: A True Musical Story

Sue Frost, producer of Come From Away

Erika Henningsen, actor in Flying Over Sunset

Tom Kitt, composer of Flying Over Sunset and The Visitor

Marc Kudisch, actor in Girl From the North Country

Debra Messing, actor in Birthday Candles

Rory O'Malley, actor in Hamilton in Los Angeles

Brad Oscar, actor in Mrs. Doubtfire

Lauren Patten, actor in Jagged Little Pill

Samantha Pauly, actor in Six

Jessica Phillips, actor in Dear Evan Hansen

Jared R. Pike, usher

Shereen Pimentel, actor in West Side Story

Kyle Selig, actor in Mean Girls

Blair Underwood, actor in A Soldier's Play

Sharon Wheatley, actor in Come From Away

Tad Wilson, actor; manager of Trattoria Dell'Arte restaurant

Introduction to Part 2

Erika Henningsen: Our cast member Laura Shoop lives in New Rochelle, which was one of the first places with a large outbreak. She was the first person who was sharing information from a personal standpoint. Her kids were being sent home from school; there were whole communities that she was familiar with that had been shut down or were in quarantine. That hadn't trickled into New York City yet, but I think Laura was the first person who said, "Oh, this is going to be big."

Jessica Phillips: Most of the adults in our cast are parents, so we were having increasingly intense kinds of conversations about what was going to happen. We were seeing it unfold in the school systems.

Tom Kitt: My son was supposed to go to Italy with his class for their big eighth-grade study tour. It's a rite of passage for those kids. I was in rehearsal for The Visitor and saw on the New York Times website the news about the outbreak in Italy, and I just started to think about my son. He's not going to go. This is not going to be a little fire. This is going to blow up. At that point, I started to sense that it was only a matter of time.

Debra Messing: I was watching the news and seeing what was happening in Italy, but I guess I just always thought that Broadway would find a way to keep going.

Tad Wilson: I was managing Trattoria Dell'Arte and in late February, early March, we were beginning to see a drop-off of our regulars who attend Carnegie Hall, which is right across the street. That's when we started buzzing, and the upper management asked me to sort of be their voice as to what was happening in the Broadway community. I wasn't really focused on that; I was focused on Carnegie Hall. I called the person over there, and they said, "We've got a couple of things that we're canceling next week." I would give a daily report to our management about what was happening. I told them it looked like Broadway was going to shut down, and our general manager, who's a wonderful, wonderful man, said, "There's no way."

(© James Monohan)

The First Week of March 2020

Joe DiPietro: We began previews for Diana on Monday, March 2, and it was overwhelming. We were focused, we were working, we had a great first couple of days, the box office was going up, and then, by Wednesday, March 4, it became clear that the pandemic was a major thing.

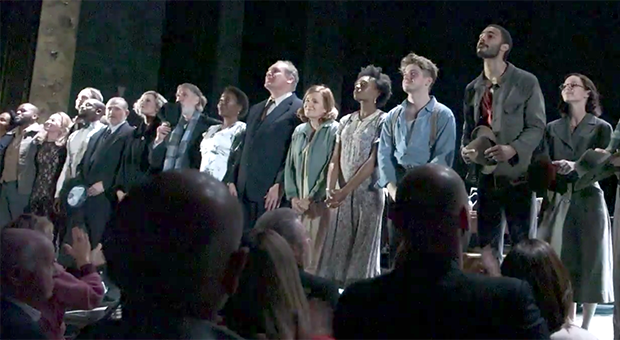

Marc Kudisch: We got to the opening night of Girl From the North Country, which was Thursday, March 5. It was beautiful. We were having a great time. I had my best friends there. I was still hugging my buds, I was still hanging out with people, but we knew that corona was around. It was more immediate than we were maybe aware of.

Tricia Baron: There were so many photographers at that Girl From the North Country opening. So many that we had to turn sideways in order to fit on the press line. Thinking back, we were crammed in like sardines. I would have my camera off to the side and then have to put it over my head to take a photo, just trying to squeeze my way in there. All the while, we have this thing looming, but none of us were taking it very seriously. There were a couple of events that I was scheduled to shoot after that, and you, David, were like, "I don't think we're gonna end up sending you to that," and I was like, "You can if you want. I'm not afraid!"

Rory O'Malley: We got on the plane from New York City [where Hamilton was rehearsing] to Los Angeles [where Hamilton would be performed] on March 5, and it was pretty empty. I didn't really put it together until we landed.

Sue Frost: We got on a plane on Saturday, March 7, to go to London to celebrate the one-year anniversary of Come From Away on the West End. We were wondering what it would be like when we got back.

Kyle Selig: All of this fell during a major cast shift in Mean Girls, right at the two-year mark. The couple of weeks leading up to the shutdown were the final performances of four original cast members [Erika Henningsen on February 22; Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed, and Grey Henson on March 8], so we had a lot of people attending to see their last shows. And then we were bringing in Sabrina Carpenter, who has millions of followers on Instagram, and we put the tour changes in with that transition. So Mean Girls was a new show. There were a lot of reasons for people to come back and see it.

Brad Oscar: My folks had come up from DC for our first preview of Mrs. Doubtfire on Monday, March 9, and part of it was to celebrate my dad's 80th birthday. We had this whole weekend planned out, and thank goodness, everyone was well. My parents were at the theater for three nights that weekend and we were all on high alert. I knew we were thinking ahead, but I don't remember thinking, "Are we gonna have a first preview?"

(© Tricia Baron)

Jared R. Pike: I started to become very conscious of what I came in contact with. Some ushers asked for gloves, and we were told that gloves weren't part of the uniform, so we wouldn't be allowed to wear them. Pretty much, the next night, there were gloves, and we were being told to wear them. I wore the gloves, but I stopped touching tickets. When you go in to a theater, they scan your ticket, and then you need to tie your shoe, so you put your ticket in your mouth to tie your shoe, and then you hand your ticket to the usher. We also have a lot of phone tickets now, so it was already awkward, because people would just hand me their phone. So I stopped touching everything.

Samantha Pauly: We were still signing programs at the stage door, but we weren't taking pictures with people so we wouldn't have to get super close.

John Raymond Barker: We would tell people to hold up the programs and the actors will sign them with their own Sharpie, so no contact was happening. But different actors had different sensibilities about how serious this was. Some were very, very careful and cautious; others acted like it was no big deal and took the programs and signed them. I would wipe down the Sharpies every night.

Sue Frost: We left it up to the actors and told them that if they didn't want to stage door, they didn't have to. As a company, they decided they wanted to continue as long as they could because they've always had a very robust stage door presence.

Sharon Wheatley: I stopped doing the stage door, oh, I don't know, maybe two weeks before the shutdown. I'm a planner.

Lauren Patten: I stopped doing the stage door a week-and-a-half prior to the shutdown. It was clear enough that it was coming into New York, and because the show was going to go on, we needed to take every precaution we could.

Shereen Pimentel: There were small kinds of restrictions happening. At first, no one could come backstage. Then, we got to the restriction of "no stage door."

Kyle Selig: It went from "Everybody wash their hands" to "there's a lot more sanitizer now" to "We're not doing the stage door anymore."

Blair Underwood: I love to go out and say hi to the theatergoers afterward. They shut that down.

Kyle Selig: Initially, it was a "Hey, you guys don't have to do that if you don't want to." And then it became "We're going to remove the barriers and not offer that as an option anymore." Which, in a way, was helpful, but then people would still just wait out there. I found myself waiting another 20 minutes before I left the building, just to give people time to disperse.

Jessica Phillips: Leaving the building became sort of complex during that period, because there were guests who still wanted to stage door and we who were not signing autographs had to step out in a tactful way, without hurting people's feelings.

John Raymond Barker: There would be a few stragglers. Thankfully, most theater fans are respectful and gracious. They just want to see the actors and say, "Great job."

Joe DiPietro: It was really hard on our actors, because they loved going out and talking to people at the stage door. They were meeting people who had come back to see the show again, which made the cast so happy. It was when they decided as a company to stop stage-dooring when we all started thinking, "We're not gonna open."

Rory O'Malley: We went into tech in Los Angeles and I'm in my dressing room watching the news thinking, "I don't think we're gonna make it to our first show." Everyone else was so busy that they weren't getting the minute-by-minute details. They made an announcement that we wouldn't be allowing backstage guests for a while. Some of the actors were disappointed. I was thrilled. I thought that announcement was going to be "We're not opening."

(© Joan Marcus)

Blair Underwood: We were sold out for the last two weeks of our run, but I started to see pockets of empty seats. The first time it really hit me, that I got the sense that people were really affected by this, was…In the final scene of A Soldier's Play, Nnamdi Asomugha has David Alan Grier on the ground, and Nnamdi spits on David. He'd been doing that for four months. This week, you heard an audible gasp from the whole front row. That's when it hit me.

Samantha Pauly: I started to notice during our last couple of previews that some of our audience members were wearing masks.

Joe DiPietro: You could feel the audiences getting nervous.

Jared R. Pike: We were trying to walk a balance of trying to protect ourselves and the audience, while at the same time, not creating a panic.

Debra Messing: I felt a heaviness, a sense of dread, fear, watching the numbers go higher and higher every day, and knowing what that meant for our company and what it meant for the city.

Lauren Patten: I was in Bloomingdale's getting clothes, because we were all preparing for the impending Tony season. Somebody recognized me from Jagged Little Pill and I went to shake her hand, and she said, "Oh, with Covid, I'm not shaking anybody's hand." That was the first time anyone had said that to me.

Joe DiPietro: That weekend, I was talking to our general manager, who handles a lot of big shows, and asked how we were doing. And he said, "My biggest hit shows, their day-of sales are going down 90 percent." And I thought, "Oh, shit."

Rory O'Malley: I went to Trader Joe's by the Pantages every night after rehearsal, just kind of gathering toilet paper, or baby formula — not that my son is on baby formula anymore, but in case there was a milk shortage. The Sunday before our first preview was the Los Angeles Marathon. We went from "How are we going to get around the LA Marathon" to "Why are we having an LA Marathon when we're about to be in a pandemic?" And then, of course, you go, "If you're worried about a marathon outside, we're next."

To be continued on February 8.