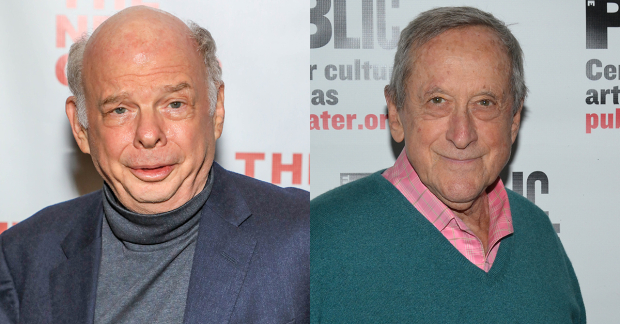

My Zoom Call With André (and Wally)

For decades now, director André Gregory and playwright/actor Wallace Shawn have been theatricalizing the end of the world. In Louis Malle's seminal 1981 film My Dinner With André, the pair debate love and money and death and whimsy over a shared meal. Their filmed productions of Chekhov's Uncle Vanya (Louis Malle's Vanya on 42nd Street) and Ibsen's The Master Builder (Jonathan Demme's A Master Builder) explore past regrets, and are probably the finest (and most despairing) versions of those plays you'll ever see (all three films are available as a Criterion Collection boxset).

As the Covid pandemic (and the events Trump Administration) wore on, Gregory and Shawn were approached by Gideon Media to turn two of Shawn's astonishingly prescient plays — The Designated Mourner and Grasses of a Thousand Colors — into multipart podcasts. Each audio play reunites the original New York casts, and Gregory once again directs them — which he has been, on and off, for decades. (His production of the former, about artist-intellectuals living through a totalitarian government, has been rehearsed and staged over and over for 21 years now, making it no doubt one of the longest ongoing collaborations in theater history.)

Here, the two artists discuss why these particular versions of the plays might be the best ones yet, and how the reality of the subjects isn't too far off from our own.

(© Tricia Baron/David Gordon)

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

There's certainly a relevance to these plays now. Do you hate that word when it comes to theater? Or is it fair to say in this case?

André Gregory: Well, yeah. Wally is sometimes called a prophet, but calling somebody a prophet suggests mystical powers. The fact is, the future is in the present. If you can look at the present, if you can look at the world you're in now with a sharp clarity, you can tell where the world is going. It's not mysterious. In rehearsals for The Designated Mourner in the late '90s, Wally, Larry Pine, Debbie Eisenberg, and I would talk about the approach of fascism in America. At the time, that was pretty far out. After Trump, sadly, the possibility of totalitarianism in this country is no joke.

Wallace Shawn: When we first did The Designated Mourner, people said "What is the political violence in the play? What are you trying to symbolize?" And I would say, "I'm writing about political violence. It's not symbolizing anything." People didn't get it. But then, you know, it's gotten easier and easier to understand.

André: And a strong theme in Grasses of a Thousand Colors is the approach of the apocalypse. When we first did the play, when people's eyes were closed to the reality of such a thing, they had trouble imagining what the play was about. Now that we have lived through Covid and the terrors of a shrinking world, Grasses, with its amazing sense of humor, is telling us about something we have already lived through.

(© Joan Marcus)

Did recording the podcast version of these plays feel like doing theater?

Wally: It's a distilled version of everything that we have ever done. The listeners won't see the costumes that we wore or the haircuts we had, but the actors feel them. We remember them.

André: When I first heard that we were going to do this as a podcast, I was slightly contemptuous, because I sort of associated podcasts with things that you did because you couldn't do theater. Since we worked on this, I realized that this manifestation of the plays, and now there have been three or four manifestations of them all over the world, could well be one of the finest. You're getting extraordinary renditions of these two plays that are extremely powerful.

Wally: I don't want to say anything that would disparage the ancient and wonderful art of live theater, but I have been thinking, since doing the podcasts, that the plays are much easier to follow [in this form]. There is a kind of nastiness about forcing people to sit in an uncomfortable chair for hours when they go to the theater. You're putting people through an unnecessary anguish. The physical experience of sitting in those seats and having to pay that much attention is undeniably hard. Whereas with the podcast, each person can do it in their own way. You can read a book in bed and you can listen to a podcast in bed. You can be folding laundry or doing whatever you want to do, and it's a wonderful thing.

André: Wally is a great storyteller, and of course, the heart of telling a story is that you can imagine the action in your own head. People always say, "My Dinner with Andre is just two people talking?" But in fact, Louis Malle did point out that the screenplay is more theatrical than Lawrence of Arabia and Bridge on the River Kwai put together, because we take you to the Polish forest and the sands of the Sahara in your imagination. You are allowed to imagine whatever the words trigger. In that sense, the podcast or more radio approach to these plays is revelatory, in a way that they have never been before.

(© Joan Marcus)

What does a post-pandemic theater look like for both of you? I know that you had been rehearsing a Hedda Gabler, and I know that the New Group was planning on a production of The Fever at some point.

Wally: That's what we believe. These days, nobody even knows if you can walk in the street. I think if I were an investor, I would not invest right now in theater.

André: And I wouldn't invest in the future of our country.

Wally: The whole future is up for grabs. To take André's point, if the Republican party manages to take over the country, and they're making progress toward that goal every day, that could be as threatening to theater as the pandemic. The first amendment is only as strong as the people who are defending it. Anything could happen.

André: Hedda Gabler, certainly because of Covid, is nowhere. The actors are spread far and wide. I don't know if I'll ever get back to it or not. And of course, we've done an Ibsen, The Master Builder, so I'm not even sure if I need to complete Hedda. Only time will tell if we work on it ever again.

Wally: The Master Builder does exist as a film.

André: If you buy the Criterion set, and of course, it would be great if you did, there are interviews that are quite extraordinary as added perks.

Wally: There are some very, very good interviews of different people about the different productions.

So much of your work has been captured on film. Designated Mourner also exists in a screen version, though it's not the production the four of you have been honing for decades now. What does it mean for you to have a record of it like the podcast?

Wally: For me…Well, obviously, André and I are both older than you.

André: Only if you combine our ages.

Wally: But we both think a certain amount about the unfair reality that we may pass from the list of living humans. Some people don't care. I'm not sure that André cares. I care.

André: I care.

Wally: Not about death itself, but about what I've done after my death. I do care about that, at the moment. I won't when that time comes. But I loved the idea that our productions, in this form, are going to live forever. Which is a privilege that theater artists rarely have. It's wonderful, to me, to have this version of our many years of work out there. And as long as anybody cares, it'll be there.