The Bitter Winter of A Man for All Seasons

(© Jeremy Daniel)

"Better a live rat than a dead lion," argues the narrator of A Man for All Seasons, Robert Bolt's 1960 historical drama about Sir Thomas More, now receiving a middling off-Broadway revival from Fellowship for Performing Arts. A Catholic martyr, More has been lionized for going to the executioner's block for refusing to sanction the annulment of King Henry VIII's first marriage to Catherine of Aragon, and his remarriage to Anne Boleyn (a union expressly forbidden by the Pope). As portrayed by Bolt, More also never directly denounces these things, preferring to keep his opinions to himself unless absolutely compelled. This makes him less a lion than a slippery Thames eel caught in the net of determined fishermen. Still, his story has real resonance in today's political climate, which the audience will easily grasp, provided it is able to stay awake.

The history undergirding the play is fascinating: Thomas More (Michael Countryman) is a statesman in the court of Henry VIII (Trent Dawson). He becomes Lord Chancellor when his predecessor in that job, Cardinal Wolsey (John Ahlin), dies on his way to face the charge of treason. The unhappy circumstances of More's promotion are compounded by the machinations of Wolsey's upstart secretary, Thomas Cromwell (a malevolent Todd Cerveris). Together with the Duke of Norfolk (Kevyn Morrow) and Archbishop Cranmer (Sean Dugan), Cromwell tries to ensnare More by making him reveal his true feelings on Henry's unorthodox matrimony. In an age when all Englishmen are called to choose between the King in London and the Pope in Rome, More tries to walk the line between both.

(© Jeremy Daniel)

FPA's revival of A Man for All Seasons feels well-timed in its response to fashionable amorality: Between the recently concluded Netflix series House of Cards and Hilary Mantel's wildly popular Wolf Hall series (which tells roughly the same story from Cromwell's perspective), the veneration of rats has never been so prevalent. Bolt holds up More as the anti-Machiavelli, a role Countryman embodies well with his dry, stiff-upper-lip delivery.

More's warning about the erosion of the rule of law feels especially prescient in our norm-smashing age: When his daughter's suitor, William Roper (also Dugan), claims that he would cut down every law in England to get after the devil, More responds, "And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned round on you — where would you hide, Roper, the laws all being flat?"

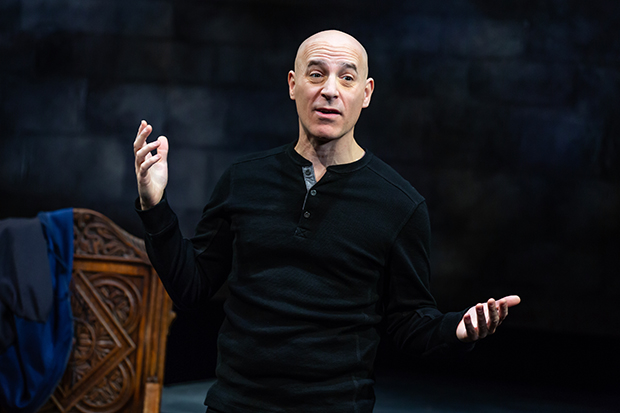

Unfortunately, few of Bolt's lines inspire chills like that one. His musty, feinting-at-Tudor style belongs to an imagined past, rather than the fleshy reality of history. That fact is underlined by the presence of a quasi-Brechtian narrator called the Common Man (a slyly charismatic Harry Bouvy), seemingly there to give us context and steer our thinking about the play. At times, A Man for All Seasons feels more like a dramatized lecture than a play.

(© Jeremy Daniel)

Matters aren't helped by director Christa Scott-Reed's by-the-book production, which would make for excellent community theater, but is underwhelming on 42nd Street: John Gromada's interstitial music seems like it was recorded for a Renaissance fair, while Theresa Squire's "period" costumes are mostly fashioned out of synthetic fibers invented long after all of these characters would have been dead (Cardinal Wolsey's robes seem to be crafted out of a red IKEA duvet). Steven C. Kemp's modifiable set of rotating panels is the most daring design element, but even that traffics in heavy oak and faux-stone clichés. At every step, the creative team has cautiously declined to reimagine Bolt's play for a new century.

The kiss of death is a plodding pace: Little tension builds as this two-hour-30-minute show crawls across the finish line, a moment that was awkwardly heralded at the performance I attended by the audience bursting into applause as the executioner's blade fell upon More's neck. Thank God it's finally over, they seemed to be saying with their hands.

(© Jeremy Daniel)

This ending is particularly inelegant considering there's still one speech left: The Common Man returns to wish us good night and remind us of the dangers of causing trouble. In this revival's one major improvement on the script, he also tells us of the fate of More's persecutors (a moment buried in the second act in the original). Norfolk: found guilty of high treason; Cromwell: executed; Cranmer: burned alive. Rats die grisly deaths too.