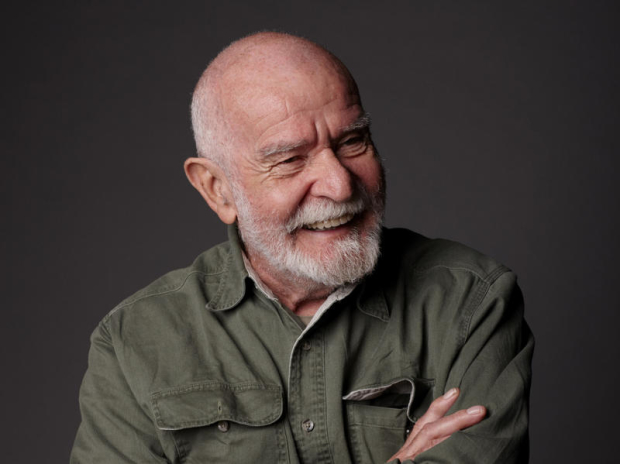

Athol Fugard Brings His Drama "Master Harold"…and the Boys Back to New York

"How am I this morning?" the esteemed playwright Athol Fugard wonders. "Bright sunshine outside, we have left the rehearsal room behind us, and today, the actors go onstage for the first time. It's an exciting day."

The South African-born Fugard has a flair for the theatrical, with a lilt in his voice that makes his enthusiasm for work infectious. And how could he not be enthusiastic? He's returning to his New York home, off-Broadway's Signature Theatre, to direct a major revival of his drama "Master Harold"…and the Boys.

Set in South Africa during the apartheid era, Fugard's play, which premiered on Broadway in 1982, tells the story of three unlikely friends, a wealthy young man named Harold and the two middle-aged African servants, Sam and Willie, who have cared for him his entire life. Inheriting roles originated on Broadway by Lonny Price, Zakes Mokae, and Danny Glover are Noah Robbins and two actors with whom Fugard has a long history, Leon Addison Brown and Sahr Ngaujah.

With the production on track for its November 7 opening night, Fugard wanted to discuss this iconic play, one he calls "probably the most autobiographical statement I've made."

(© Gregory Costanzo)

What was the impetus for your writing "Master Harold"…and the Boys?

In those early years of building my career as a playwright, a thought kept nagging at me. "You had two beautiful men in your life as a young boy, two men, Sam and Willie, who worked for your mom." They were surrogate fathers, playmates, teachers, everything that a boy needed. That's an anomaly, of course, black men being all of that for a white boy in apartheid South Africa. But that, paradoxically, was the nature of the relationship.

I kept thinking of a two-hander. "How can I do justice to them?" And I tried, I don't know how many times, to find the dynamic that is so important in a play. I can't remember what it was that put the thought in my head, but suddenly when I got the little boy in there with them, "Master Harold" came to life.

How did this revival come about?

It goes back to the last days of the beloved [Signature Theatre artistic director] Jim Houghton, god rest him. Jim said "I think it's time for "Master Harold"…and the Boys, what do you think?" I was bursting with a resounding yes. Synchronicity, I think, is the word. I had been looking at the play and thinking about it, just quietly by myself. To suddenly have this confirmation come from Jim was absolutely amazing for me.

(© Monique Carboni)

Tell me about the casting process. This production reunites you with two of your frequent collaborators, actors Leon Addison Brown and Sahr Ngaujah.

There were a lot of candidates for Sam, some magnificent African-American actors. I worked my way though auditions and looked at reels, and I didn't click with anyone. Then, suddenly, I turned to my wife, my associate director, Paula, and I said "What about Sahr and Leon [whom Fugard had directed in his play The Painted Rocks at Revolver Creek]?" Paula lit up and I lit up.

The foundation of my work has been repeated use and challenging of a core group of actors. Zakes Mokae, who played Sam in the original, was one of them. Zakes and I had been through the bloody mill in terms of surviving and keeping our friendship and our creative relationship in tact during the apartheid years. I built on Zakes and got to know him and challenged him.

The first time I used Leon was in The Train Driver. I began to have a signal of his potential. The folks at Signature said, "If you feel that strongly, go ahead. You can challenge him out of his skin." That's exactly what I've always done with actors. And then Paula absolutely went for Sahr as Willie. My god, the work he has done in the rehearsal room is bloody amazing. There were those roles wrapped up, and then began the search for the all-important Master Harold. Our very first encounter with Noah left me with no doubt. It's three actors from heaven.

Do you look at "Master Harold" as autobiographical?

It's very autobiographical. To date, it is most probably the most autobiographical statement I've made. I've taken liberties, of course, but I was that little boy, privileged to have those two men in my life. I was that little boy who abused them at a moment of terrible confusion and pain in my life. The shame of that moment, the climactic moment in the play, I will take with me to my grave. You can't wash away something like that.

What's next for you after this production?

I've got a novel called Dry Remains, which Paula flagellates me with periodically, and says, "When are you finishing it?" I think it's a good piece of writing. It's halfway there. And I've also got ideas for two plays. Both of them are sketched out rather roughly at this point in my notebook. Without having pen and paper in my life, I'm a dead man.

(© Gregory Costanzo)