"Another National Anthem": What Assassins Tells Us About the American Identity

(© Martha Swope)

When Assassins first opened at Playwrights Horizons in 1990, it left unsettled audiences in its wake. After revolutionizing the format of the American musical with Company, and inverting Western theatrical expectations with Pacific Overtures, composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim had appeared to reach his stride with larger-than-life productions like Sweeney Todd, Sunday in the Park With George, and Into the Woods, each of which lived in its own specific cultural world.

In many ways, Assassins was Sondheim's return home. His first splash on Broadway had been as the lyricist for West Side Story, a decidedly American musical, which was immediately followed by Gypsy, an ode to the American institution of vaudeville. Whereas those shows had mythologized aspects of American culture, Sondheim had also flirted with American disillusionment in Company, Follies, and Merrily We Roll Along. With Assassins, Sondheim and book writer John Weidman removed the Vaseline from the lens as they told a startling stark story about the twisted and grisly reality of the American dream.

Even now, 30 years after the original production closed off-Broadway at Playwrights Horizons, this seminal work continues to reflect just how easily the American dream can warp into the American nightmare.

By 1990, the tapestry of American exceptionalism had begun to fray. With each previous decade, there had been a tear. In the 1980s, conservative politics desperately tried to uphold the status quo as the Cold War crumbled and the common enemy, the USSR, began to collapse. In the 1970s, the Vietnam War came to an end, with the brutalism of the American military complex presented before the American people as not heroic but horrific. And in the 1960s, President John F. Kennedy was shot, shattering the impenetrable aura of the American presidency. Kennedy's assassination, and the lack of explanation given by Lee Harvey Oswald before his own murder, left the country grappling with the most uncomfortable of questions: Why?

In Assassins, the answer is simple: "Why not?" The first song in the score "Everybody's Got the Right," spells it out plainly:

"Everybody's got the right to be happy

Don't stay mad, life's not as bad as it seems

If you keep your goal in sight

You can climb to any height

Everybody's got the right to their dreams"

On the surface, this advice is simply a restatement of the well-trodden myth of the American dream — keep your eye on the prize, and you'll get what you want. No questions, no concessions, only blind faith in fate and in the concept of a meritocracy. This idea, that anyone could become someone in America, was the foundation on which the story of American exceptionalism was built. Millions of immigrants streamed into the country in order to cash in on that promise, even if the only way they could succeed was by trampling whoever got in their way.

(© Joan Marcus)

A side effect of exceptionalism is individualism. The singular holds value, rather than the collective. A person has to be quantified in order to have worth, and the higher their perceived value, the greater respect they are given. The only way to rise in this individualistic class system is through great acts. The urge to prove oneself is perhaps the defining aspect of American culture.

One of the best ways to make a name for yourself is to associate with a person of high social status; the more indelible, the connection the better. It is why celebrities are surrounded by sycophants, brands strike endorsement deals with influencers, and why millions of voters and politicians continue to cling to former president Donald J. Trump and the Alt-Right in spite of the insurrection at the Capitol. The violence and bloodshed, while publicly abhorred, are personally absorbing. This is not a trait unique to Americans, but its effects are magnified by American culture's obsession with being tragically titillated.

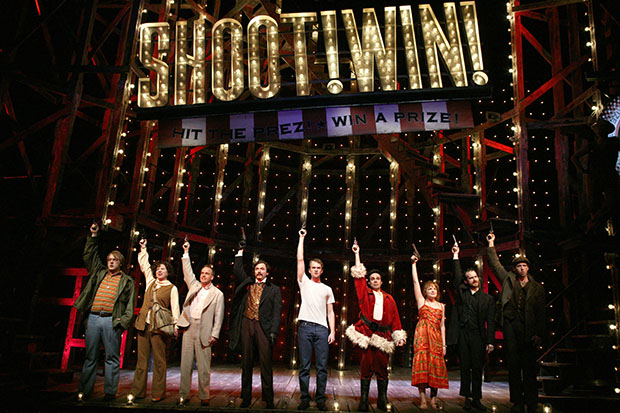

Assassins was one of the first musicals to acknowledge the entertainment Americans find in carnage. Sondheim and Weidman took nine presidential assassins (successful and failed), transported them into the same time and place, and allowed them to commiserate and connect in a warping of the traditional revue format. Instead of heroes, audiences were given deluded villains, ranging from a racist celebrity with a hero complex (John Wilkes Booth), to a Santa suit-clad manic depressive (Samuel Byck). The audience was brought into a world where they found themselves empathizing, perhaps even agreeing with, the assassins' lines of reasoning.

They were no longer ideological boogeymen, cast off by "proper" society as loathsome; they were distinctly human. You could see yourself in them, which made their stories even more shattering. Audience members were forced to grapple with the complicated underbelly of American culture in a way that many of them had never experienced. Sondheim and Weidman were able to leverage their professional reputation to get theatergoers in the door and they left changed, even if they didn't recognize it.

When Assassins closed on February 16, 1991, plans were made to bring it to Broadway, before the idea was scrapped due to a rise in nationalism during the Gulf War. A decade later, it was again attempted, only to be stymied by the events of 9/11 and the patriotic resurgence that followed. It finally came to Broadway in 2004 with an additional song illustrating the feelings of the American people, "Something Just Broke," and the show was just as startling then as when it was first presented. Ultimately, Assassins speaks not to how America wants to be remembered, but to who America is, underneath the layers of pageantry and posturing: a young, tempestuous country, desperate to prove itself, and willing to endure whatever it must to leave its mark.

(© Joan Marcus)