Tamburlaine, Parts I and II

Theatre for a New Audience presents a powerful new mounting of Christopher Marlowe’s epic play, for the first time in a major New York production in 58 years.

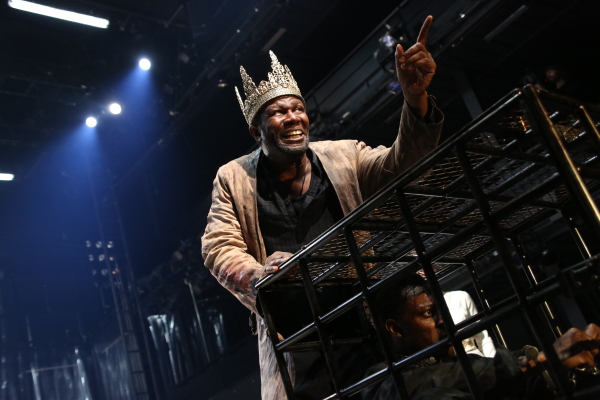

(© Gerry Goodstein)

In a central square of Tashkent, Uzbekistan, where once stood a bust of Karl Marx, a giant statue of the 14th-century conqueror Amir Timur (or Tamerlane), astride a horse, threatens to cut down any challengers. By all estimates, millions of people died as a result of Tamerlane's brutal campaigns. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, however, Uzbek strongman Islam Karimov has sought to elevate Tamerlane to the position of national hero, drawing not-too-subtle parallels between the infamous butcher and himself. You might wonder why any sane leader would want to invoke the memory of so murderous a historical figure, but after viewing Theatre for a New Audience's excellent production of Christopher Marlowe's Tamburlaine, Parts I and II, you'll have a good idea why. Six hundred years after his death (and over 400 years after Marlowe wrote his breakthrough play), Tamerlane's legend still has the ability to inspire fear and admiration, disgust and pride.

Written in 1587 (and only vaguely historically accurate), Marlowe's play eloquently captures the ambivalence surrounding the figure of Tamerlane. Part I charts his meteoric rise, starting with his first great victory over Persia. After defeating the foolish King Mycetes (a very funny Paul Lazar) and placing Mycetes' treacherous brother Cosroe (Saxon Palmer) on the Persian throne, Scythian warrior Tamburlaine (John Douglas Thompson) double-crosses Cosroe and takes the crown for himself. He makes captured Egyptian princess Zenocrate (Merritt Janson) his queen, then moves against the immensely powerful Turkish Emperor Bajazeth (Chukwudi Iwuji) and his 15 tributary kings. These men of noble birth scoff at the notion that they could fall to a nobody from the barren steppes, but Tamburlaine has the last laugh when he leads them away in chains. "The god of war resigns his room to me, / Meaning to make me general of the world," he declares, believing himself to be more powerful than any god.

Marlowe's story of a lowborn shepherd humbling great kings and cursing God is downright radical when viewed in the context of Elizabethan England — a society governed by a hereditary monarch claiming to rule by divine right. Even today, Tamburlaine's words and actions have the ability to conjure a potent populist frenzy. During a discussion between Tamburlaine and his lieutenants about whether they would like to be kings, all agree they would. Thompson turns to the audience and asks, "And so would you, my masters, would you not?" We all nod in agreement, some shouting back at the stage like groundlings in an Elizabethan theater, transfixed by the uncommon tale of ignoble triumph before us. Thompson passionately embodies the dual nature of Tamburlaine, a people's hero whose wrath is unspeakably cruel.

Indeed, while we're happy to see the arrogant Bajazeth and his Empress, Zabina (Patrice Johnson Chevannes) cut down to size, we find it harder and harder to stomach Tamburlaine's inhuman malice. With their heartbreaking performances, Iwuji and Chevannes strike the first blow against Tamburlaine's hero status. As Bajazeth languishes in a cage, surviving off Tamburlaine's table scraps, Zabina implores, "Eat, Bajazeth; let us live in spite of them." Even though we laughed at their downfall just a scene before, we sympathize with their desperation and with Zabina's grief when she goes to fetch water for her husband, only upon her return to find him dead. It's very difficult to get behind the merciless Tamburlaine as his own hubris begins to exceed even those he's conquered.

Of course, the bigger they are, the harder they fall. In Part II Marlowe treats us to Tamburlaine's spectacular decline, which sees the death of his beloved wife. To add karmic insult to injury, our macho protagonist is cursed with an "effeminate" firstborn son (James Udom). While the sight of Tamburlaine riding around the stage on top of a cage full of crowns drawn by enslaved despots is infinitely amusing, it's hard to laugh. Thompson terrifyingly portrays a man who is increasingly unhinged and dangerous, especially as he confronts his own mortality.

Director Michael Boyd’s fast-paced staging is simultaneously austere and epic. Scenes bleed from one to another with little downtime, never allowing us to catch our breaths in between. Nineteen actors play over 60 roles, transporting us across three continents using only Tom Piper's relatively bare stage. Piper's costumes exude a quasi-futuristic Waterworld chic, with body-length leather coats and knee-high Goth boots. Deaths are neatly stylized by choreographer Sam Pinkleton using simple gestures and buckets of stage blood, eliminating the need for elaborate fight scenes. The whole event is underscored by Arthur Solari's ambient percussion, which accentuates the tension onstage and gives us a clue about the carnage happening in the wings.

The nonstop thrills of this new production make its three-and-a-half-hour run time fly by. Boyd and company have proven Marlowe's text to be fascinatingly modern and infinitely watchable, over four centuries after its premiere. While Marlowe's hubristic monster doesn't fully do justice to the historical Tamerlane, neither does Karimov's wise and fair conqueror. The fact that Tamerlane still inspires such varying reactions and revisionist history is proof of his lasting effect on the human imagination.