The Notebook Is Very White: Does Its New Musical Adaptation Have to Be?

A closer look at Broadway’s responsibility and opportunity to set new standards of inclusivity as some of Hollywood’s whitest properties head for the stage.

(© New Line Cinema)

On January 3, Ingrid Michaelson went on Good Morning America to announce that she would make her theatrical debut as composer for a brand-new musical version of The Notebook, Nicholas Sparks’s tear-jerking story of lovers from opposite sides of the tracks in 1940s South Carolina. Sparks’s penchant for sweeping romance and Les Misérables-ian death scenes make Broadway a natural next frontier for a man who has already conquered the book and film industries. And yet, the project (which will feature a book by playwright and This Is Us producer Bekah Brunstetter) may be much more of a gamble than its $116 million box office and iconic Ryan Gosling-and-Rachel-McAdams-making-out-in-the-rain gifs suggest.

Google “Nicholas Sparks movies,” and you’ll find a 11 pairs of white faces staring lovingly into each other’s eyes (usually in a field…sometimes on a beach…almost always at sunset). The Notebook may be the most glaringly colorless project coming down Broadway’s pike, but with adaptations like Mrs. Doubtfire, The Devil Wears Prada, and Almost Famous joining it on the list of pending musicals, homogeneity is something that stage-bound Hollywood titles seem to have in common. And set against the backdrop of post-Hamilton Broadway within a present-day-Trump America, it will also be something they have to reckon with.

In the past year alone, Disney’s heroic (and Nordic) Kristoff, J.K. Rowling’s brilliant Hermione, and King Kong‘s no-longer-distressed-damsel Ann Darrow have become people of color. Actors Equity, meanwhile, has been bestowing the Extraordinary Excellence in Diversity on Broadway Award since 2007. The award plants a flag in the assertion that diversity is something to be celebrated and rewarded in a community where, according to statistics compiled by the Asian American Performers Action Coalition, white actors accounted for around 80 percent of roles on and off Broadway between 2008 and 2015.

(© Manuel Harlan)

That number has been generally trending downward, with a significant drop in the 2015-16 season when Hamilton, The Color Purple, Shuffle Along, On Your Feet!, and Allegiance helped raise the roles for minority performers to 35 percent. But the shifting ground on Broadway extends beyond hard-and-fast statistics. When Hamilton arrived at the Richard Rodgers, it came to represent the ultimate alignment of commercial interests and progressive ideals. If America’s founding fathers can be painted with the colors of our modern-day melting pot and gross on the order of $3 million a week, does anyone have an excuse not to prioritize fair and diverse representation? It’s easy to answer that question with an unqualified “no” when you have the luxury of speaking in generalities, but the people in charge of granular creative decisions have had to feel the growing pains that come with navigating this increasingly complex conversation.

Just one month ago, director Gregory Mosher exited Roundabout Theatre Company’s spring 2019 revival of Arthur Miller’s All My Sons after Miller’s estate, overseen by the late playwright’s daughter Rebecca, objected to Mosher’s intention to cast black actors as siblings Ann and George Deever. At the time, Miller had already greenlit Marianne Elliott’s upcoming London production of Death of a Salesman featuring an African-American Loman family (led by Wendell Pierce), as well as a multicultural production of The American Clock, directed by Rachel Chavkin and also opening in London this year.

In a statement about the All My Sons revival, however, Miller described Mosher’s vision as “not fully thought out,” saying that making the Deever siblings people of color in 1947 suburban Ohio would effectively whitewash history by disregarding the predominantly racist attitudes of the time. Particularly in a production led by two white actors — Annette Bening and Tracy Letts as Kate and Joe Keller — the world of the play would translate as one aware of race but willfully ignoring it in a way that doesn’t make thematic or historical sense. It was reported that Miller suggested mitigating that problem by opening all roles to actors of color, but Mosher rejected the idea and left the project (Jack O’Brien is now directing).

The work of Arthur Miller likely inspires more fervent artistic and scholarly opinions than that of Nicholas Sparks, but it’s easy to imagine the closed-door casting conversations about The Notebook musical going in a similar direction. While it could be relatively simple work to diversify Mrs. Doubtfire‘s suburban San Francisco family, or the world of middle-aughts fashion in The Devil Wears Prada, or even the ’70s rock-and-roll tour bus from Almost Famous, The Notebook is set in World War II-era South Carolina. If 1940s Ohio is bubbling with racial strife, remember that South Carolina was the first state to secede from the union — and Allie’s parents can’t even handle the thought of her dating a white quarry worker who looks like Ryan Gosling.

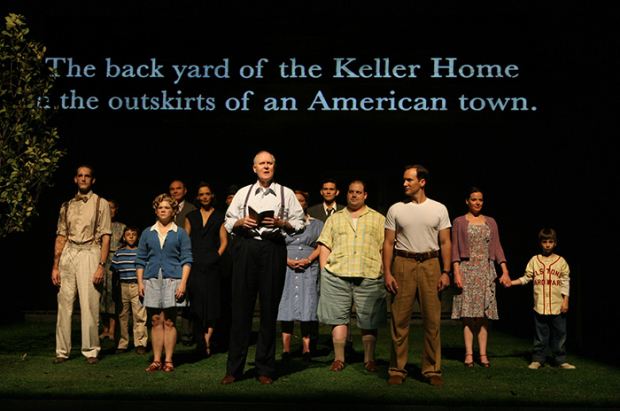

(© Joan Marcus)

So where does that leave The Notebook team? They could willfully ignore the cultural milieu for the sake of inclusive casting, but to the detriment of comprehensive storytelling. They could turn The Notebook into a racial Romeo and Juliet story, which would require a fully rehauled narrative. They could accept the option Gregory Mosher rejected and make race irrelevant with a fully colorblind cast. Or, they could make the easiest but perhaps most symbolically regressive choice — keep the story as white as it has always been.

After all of these mental backflips, it’s reasonable to wonder: Should diverse casting be such a deeply considered choice, or should it not have to be?

Requiring individual casting choices to clear so many hurdles, one could argue, is the truest sign that the industry is not an organically level playing field. Or, to call upon our latest cultural catchphrase, it could be a sign that the industry has become muddled by a game of “virtue signaling.” In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter about the #OscarsSoWhite conversation, TV and film casting director Victoria Thomas acknowledged and expressed resistance to that eventuality: “My feeling is that it’s about getting the world right, whatever that world is, and some of those worlds may not be diverse,” she said. “If that is the case, then that’s the case. It’s not about diversity for diversity’s sake.”

Perhaps all creative choices should have exclusively artistic motivations. And yet, that 80 percent statistic makes a compelling argument for balancing the representational scales by any means necessary. Broadway at large is clearly still debating which school of thought leads to the conception of inclusivity that most closely matches our ideals of fairness and equality. But wouldn’t it be something if Nicholas Sparks, of all people, was one of the people who helped us figure it out.