Pacific Overtures

George Takei stars in a revival of this Sondheim-Weidman musical about the emergence of Japan onto the global stage.

(© Joan Marcus)

You may think that 1853 Japan bears little resemblance to the United States in 2017, and outwardly you would be right. Still, there is something eerily familiar in the knowing smiles and proud postures on display at Classic Stage Company in the off-Broadway revival of Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman's Pacific Overtures. These people not only think that their way of life is exceptional, but sincerely believe that it will last forever. Of course, hubris is an essential ingredient in any tragedy.

The categorization of Pacific Overtures as a tragedy depends very much on how you think the last 164 years have played out for the Japanese people: The musical tells the story of Commodore Matthew Perry's American naval expedition to Japan from a Japanese perspective. At the time, Japan was a feudal society completely closed to foreigners. When Perry's warships are spotted off the coast of Uraga, the ruling Shogun (Thom Sesma) sends minor samurai Kayama Yesaemon (Steven Eng) to tell them to leave. The American sailors ignore Kayama until he enlists the help of Manjiro (Orville Mendoza), a Japanese fisherman recently returned from Massachusetts. Despite Kayama's attempts to convince the outsiders to go away, the Americans are followed by British, Dutch, Russian, and French delegations, each wanting a slice of this shiny new market. As foreign traders disrupt the peace and stability of the island with Western goods, inventions, and manners, the Japanese people have to decide whether they will embrace this new world or rage against it.

(© Joan Marcus)

Weidman's book feels incredibly prescient in the context of today, when the political discussion has shifted from right-versus-left to open-versus-closed. Eng and Mendoza live that transformation in their performances, embodying the cycle of disruption, accumulation, and reaction that accompanies any attempt to integrate a closed society into a wider community of nations. Nowhere is this clearer than in "A Bowler Hat," a masterpiece of musical storytelling that condenses 15 years into one song: By the end, the two men are practically different characters, something that is made apparent here through minimal costume changes and physical alterations.

John Doyle, who has previously distilled Sondheim in smartly pared-down productions, proves to be the ideal director and set designer for this show that is best presented with elegant simplicity. He divides the audience in half with a modernist hanamichi, the runway stage commonly used in kabuki. We surround this platform, which plays the part of the island of Japan itself: The denizens of this floating kingdom look out on us barbarians with a combination of pity and contempt, an attitude that slowly darkens to fear over the course of 90 minutes.

Ann Hould-Ward's streetwear costumes give the impression of contemporary people coming together to tell a story about the past. Small items (spectacles, print cloths draped as robes, an American flag handkerchief) are used effectively to shift characters in a show in which almost everyone plays multiple roles. Jane Cox's lighting is similarly useful in transforming the stage and directing our attention.

Not all of the design choices are well thought-out though: Sound designer Dan Moses Schreier accompanies every death with a cartoonish scream, when Cox's red wash and the bowed heads of the actors is enough to send the message. During the diplomacy pastiche number "Please Hello," an American diplomat carries a flag with 50 stars when there would have only been 31 at the time of the play. One might claim this is indicative of America's ongoing passion for international adventurism, but then how does one explain the hammer and sickle banner borne by the Russian envoy? Such historical anachronisms serve to distract us from an otherwise clear and concise presentation of the story.

(© Joan Marcus)

Fans of Sondheim's score may be disappointed by the absence of the palace intrigue number "Chrysanthemum Tea," a fun but ultimately unnecessary song that slows the progress of the story while introducing new characters that never reappear. Beyond that omission, this ultra-lean production retains every other number in the score and they all sound gorgeous under the direction of Greg Jarrett, who leads a two-tier orchestra with an entire level solely devoted to percussion. The sound is magnificently rich in this intimate space.

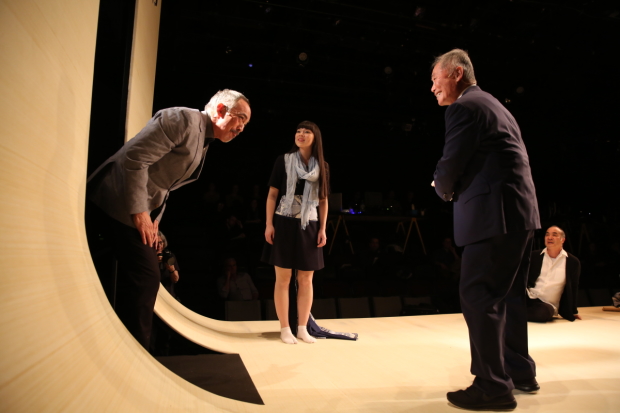

Pacific Overtures also benefits from the performance of George Takei as the Reciter, a narrator who takes us through this history. Takei brings grandfatherly presence to the role, helping to reinforce the feeling of modern Japanese people looking back on the past. Takei's tendency to overact seems natural in this highly stylized world, which is so much about ritual and ceremony.

(© Joan Marcus)

Megan Masako Haley plays the most inscrutable part in this production: She briefly occupies the minor role of Kayama's wife, Tamate, but she remains onstage long after Tamate is out of the picture. She silently observes everything with a catlike sense of wonder and caution. She is the spirit of Japan in one body, mournfully reviewing the past while peering apprehensively into the future. She has yet to make a decision about her next move, but as the explosive finale number suggests, we ought to brace ourselves for what happens when she does.