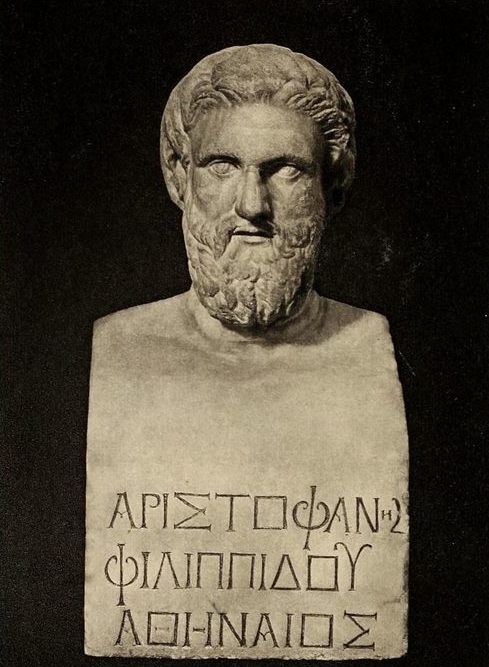

Today, Would Aristophanes Tweet?

When did the theater start ruffling political feathers? Only about 2,500 years ago.

When today's world gets especially stressful — as it definitely is just now — my mind wanders back to older and happier times. So during these recent agonizing months, I've naturally been thinking about ancient Greece. And particularly about the time of Cleon.

You may or may not remember Cleon. He essentially controlled Athenian politics after the death of Pericles, from around 429 B.C. until his own death in 422. Some modern scholars have tried to make a case for Cleon, but he generally seems not to have been, by anybody's standards, an honest guy. Under his sway, Athens got more and more deeply embroiled in a messy and endlessly prolonged war with Sparta in the Peloponnesus. Meanwhile the city's economy went downhill along with its political principles and its ethical values. By the end of Cleon's time, Athens was heading to the bedraggled finale of its great cultural era. Its fame as the cradle of democracy, the glorious home of poets and thinkers, was starting to fade. The military quagmire into which Cleon and his supporters had helped to drag it would, by the end of the fourth century, leave it easy prey for conquest.

Cleon was able to gain so much influence, it seems, because he appealed to a wide segment of the population. Though not well-educated or refined, he was a skilled orator; he had a loud voice, and his rough, unpolished speeches made a great impression on ordinary folk. He attacked the aristocracy and the educated class — most of whose members loathed him as a demagogue — for being snobbish and elitist. He puffed up Athenian patriotism by reviling the Spartans as vicious, stop-at-nothing enemies, and refusing to listen to any peace overtures. He also tossed the Athenians a modest monetary plum by increasing the tax burden on the smaller outlying cities that were its allies. Cleon was full of clever little tricks like that.

(© Paul Kolnik)

And that's precisely where the trouble flared up between Cleon and one of the two great theater artists of his time, Aristophanes. In 426, when Aristophanes was just starting out as a playwright — he may have been no more than 19 — he turned out a comedy called The Babylonians at the big spring festival the Athenians held every year in honor of Dionysus. In that play, he depicted the city's allies as foreign slaves doing the grind-work at an Athenian-owned mill — and being maltreated by an overseer with a striking resemblance to Cleon. Since officials from all the allied cities traditionally attended the festivals, this gave Cleon the chance to accuse Aristophanes of having slandered Athens in front of foreigners.

There were no social media in ancient Greece except marketplace gossip, but the accusation went viral anyway, and Aristophanes was put on trial. We don't know the details, but he seems to have gotten off lightly. The accusation must have rankled, though, because he immediately returned to the attack. The Babylonians is lost, except for a few fragments, but Aristophanes' next play, The Acharnians — the first of the 11 works by him that we do have — was yet another merciless satire on Cleon, who remained one of the poet's principal targets during his next four plays. The Athenians must not have minded too much, since The Acharnians won first prize at the Lenaeoa, Athens's annual winter comedy festival, in 425. He had won first prize for The Babylonians, too. In fact, all the plays in which Aristophanes held up Cleon to devastating ridicule won prizes: The Knights took first prize in 424 and The Wasps came in second in 422. The only play in this period for which Aristophanes got no prize was The Clouds (423), in which Cleon is only a marginal target.

Comedy had privileges in Athens that are hard for us to imagine today, as well as high demands to satisfy. The plays were expected to be filled with slapstick, lewd jokes, and double entendres, while also being poetically beautiful, witty, and fantasticated. Plus, they were expected not only to allude to topical events and real people, but to name names. Picture a coherent work that combines the best elements of Cyrano de Bergerac, a 1920s musical, a burlesque sketch, and Saturday Night Live, and you'll see the sort of challenge that Aristophanes and his colleagues had to face.

To top things off, in the middle of every Athenian comedy, until this classical form gave way to successors closer to something more like comedy as we understand the term, there came an event known as the "walk downstage" (parabasis), a sort of moralizing intermission when the action stopped, and the Chorus took off its elaborate costumes and masks, and strode to the front of the stage to hector the audience, in the playwright's voice, on some pressing issue of the day. Though this section, like the rest, was in verse, chanted or sung, and was expected to be wittily expressed, it departed strongly from the rest in tone: Add to the mix described above something like the choruses of Brecht's didactic plays or the final chorus of Blitzstein's The Cradle Will Rock.

Despite those upsurges of earnestness, Aristophanes' form of classic Greek comedy — the scholars call it Old Comedy — was essentially frivolous and, apparently, good-humored. Apart from Cleon, who seems to have been as touchy as today's ill-tempered tweeters, those ridiculed are said to have taken the comic abuse in good part: When the actor playing Socrates in The Clouds made his entrance, the story goes, Socrates himself stood up in the audience to show the crowd how good the mask-maker's likeness was. I'll look at some of the specifics of Aristophanes' plays next week.

To read Part II of this Thinking About Theater column, click here.

Michael Feingold has twice won the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism, most recently in 2015 for his Thinking About Theater columns on TheaterMania, and has twice been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Criticism. He serves as chairman of the Obie Awards and has also worked as a playwright, translator, and dramaturg.