A British Seaside Town Goes Wild in Feral

(© Amy Downes)

The word "feral" is most commonly applied to domesticated animals that have escaped captivity (or have been abandoned by their humans). A similar situation seems to be occurring in Tortoise in a Nutshell's collectively written installation play, Feral. The abandoned party is not a house cat, however, but the population of an idyllic British seaside town. Now making its New York debut as part of the Brits Off Broadway series at 59E59, it employs an incredibly complex design to convey a frustratingly simplistic narrative.

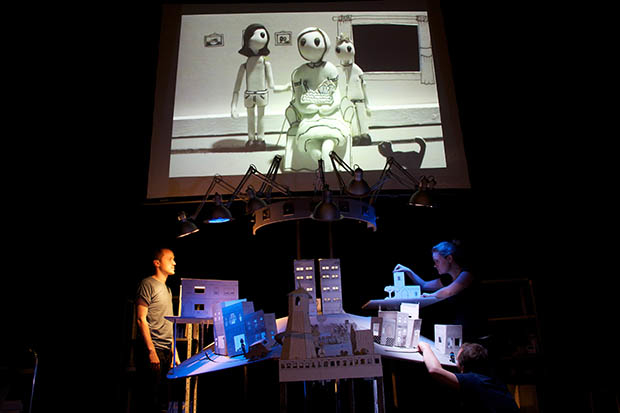

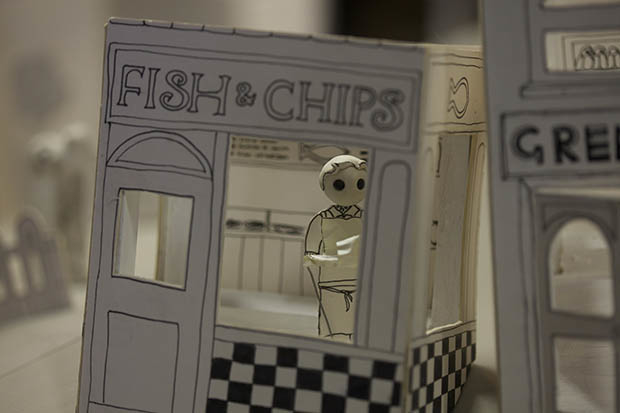

First the design: Director Ross Mackay has collaborated with scenic designer Amelia Bird to create a model town, which three of the performers (the steady and dexterous Alex Bird, Arran Howie, and Matthew Leonard) build live at the top of the show. Joe, our protagonist, introduces us to his mum and sister, Dawn. Close-up video projected on an upstage screen allows us to see the details of their little town as Joe and Dawn walk by its landmarks: the butcher's, the chip shop, the pre-Victorian lighting emporium.

(© Amy Downes)

Lighting designer Simon Wilkinson illuminates these details with a cluster of desk lamps extending over the central structure like spider's legs. Sound designer Jim Harbourne produces live sound effects to inventively convey the hustle and bustle of the town. Mackay even gives us a visceral sense of the fun park on the pier through the infused scent of popcorn and sweet buns. Populated entirely by black-and-white figures with beady eyes and no mouths, Feral looks like the '60s stop-motion animation series Trumpton as reimagined by Tim Burton.

But not all is well: The mayor has big plans to open what he calls a "supercade," which seems to be a large arcade or kiddie casino. Joe, a young boy obsessed with superheroes, becomes convinced that the supercade will be their clubhouse. Older residents see it as a pork project that will fail to deliver on promised jobs while having a deleterious effect on the town — and their fears are confirmed in spectacular fashion. Almost immediately after the supercade opens, local businesses close, crazed drunks take over the streets, and the vicar loses his marbles. It's a sad story, but it honestly feels like too much blame to lay at the feet of Chuck E. Cheese.

(© Amy Downes)

A more nuanced script might examine decades of austerity policy fortified by Thatcherite indifference toward anyone unwilling or unable to adapt to a rapidly shifting economy. A deeper dive still might look at the role of centuries of British class warfare in the erosion of communities like this one. Unfortunately, the highly visual but sparingly verbal form Feral takes is ill-equipped to process such complexities. The overall design is impressive, but the story leaves us scratching our heads.

We look for clues in the few words to which we are exposed, including the provocative title: "Feral" is a word for animals, but in British tabloids, it is most commonly applied to working-class youths (like the ones seen in a riot at the end of this play). That raises a question: Who abandoned these kids to their feral condition? Parents? Teachers? The state? Feral offers no answers, as it barely asks any questions. Its simple cause-and-effect masks a more complicated truth about the way communities hold together in times of change, and how they fall apart.