In His Own Words: Dane Laffrey Creates Sets for Spring Awakening, Fool for Love, and More

(© Jen Silverman)

In the span of one month, scenic designer Dane Laffrey had four productions open in New York. "They happened in a variety of different timeframes," Laffrey says of his busy fall, which saw his work on Broadway's Spring Awakening and Fool for Love, as well as off-Broadway's The Christians and Cloud Nine, take center stage.

Cloud Nine was a cold open at the Atlantic Theater Company. The Christians came to Playwrights Horizons from Kentucky's Humana Festival in 2014, and in the summer of that year Fool for Love originated at Williamstown Theatre Festival and Spring Awakening in a Los Angeles black box. "Cloud Nine was the only one that was in the normal season pipeline at the Atlantic when they hired me," he points out.

Despite it seeming like a frenzy of activity, Laffrey had already carved out a unique look for each production before they opened in New York. He took TheaterMania through his creative process and gave us a glimpse into his vast imagination.

The Christians

Humana Festival (2014); Playwrights Horizons (2015); Mark Taper Forum (2015)

Lucas Hnath's thought-provoking play explores what happens when the pastor of a megachurch declares a new set of beliefs for his congregants. The action is set during his sermon.

(© Dean Laffrey)

In our original understanding of it, the goal was to put the megachurch on stage. That's what we did at Humana successfully. Then, when we approached it for a second time, I said "No, what we need to be doing is turning the theater into a megachurch," which was certainly more possible at Playwrights Horizons and at the Mark Taper Forum, where we're about to do it. It became a response to the existing architecture [of the theaters], melding that with the research of what these megachurches look like. That was the goal: make it as authentic and unique an experience from the moment you walk in the door.

The chairs and lectern all came from, it's not called this, but it's like "ChurchSupplies.com," some catch-all website for outfitting your Church. The chairs were originally procured from the manufacturer in North Carolina.

The Mark Taper Forum is a great place for this project to conclude, assuming it concludes there. The Taper does a lot of the work for us. The exercise of that has really been about distilling what the architectural components [of the theater] are and figuring out how to merge it with the architecture that we know we need, where the chairs are, where the choir risers are, where the Cross is. The setups have basically been identical. The proportions are stretched out at the Taper. What happens beyond that is a response to the size of the room and what the features are.

(© Joan Marcus)

Fool for Love

Williamstown Theatre Festival (2014); Samuel J. Friedman Theatre on Broadway (2015)

Nina Arianda and Sam Rockwell star in Sam Shepard's drama, which is mostly set within a seedy motel. On the periphery, an old man sits, watching the action.

(© Dane Laffrey)

That space was based on a lot of research of weird old Mojave Desert motels. What those are and what Sam asks for in the script are one and the same. We were concerned for a sense of hyper-naturalism, with a proper sense of scale with the walls and how thick they are, and the ceiling at the right height. It wants to feel like they just don't quite fit in there.

The bigger design challenge is how you justify the space around it, and how you make sense of the old man sitting on the fringes and just watching it. That's such a theatrical device, mixed with something we thought wanted [to be] gritty. We discovered that it had the architectural facets of a ruin rather than a real space. There isn't a number on the motel room door; there's just an outline of where a number was.

We knew about [the transfer to Broadway] almost a year before we did it. We didn't change a lot about it. The set appears basically identical [to the Williamstown production]. By necessity, it's a bit scaled up for sightline reasons in the Friedman.

(© Joan Marcus)

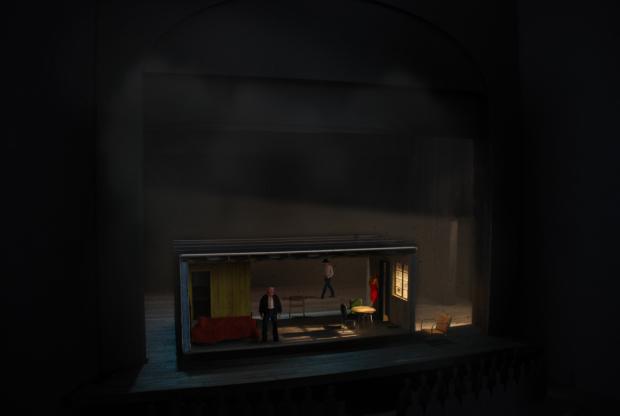

Cloud Nine

Atlantic Theater Company (2015)

With Caryl Churchill's Cloud Nine, Laffrey completely reconfigured the Atlantic's Linda Gross Theater. In bringing Churchill's time-and-place-jumping comedy to life, Laffrey razed the auditorium and designed a series of wooden bleachers with a playing space in the middle.

(© Dane Laffrey)

My impulse to move in the direction of special reconfiguration, as opposed to scenery, was because I just couldn't picture what [the show] looked like… It was partly because of the play's two totally divergent styles and not wanting to comment on that.

We moved away from the idea of there being a set, which made us immediately think that we didn't want to do it in a proscenium. That room is seventy feet long. We looked at every possible [special] iteration. Is it a tennis court? Is it a three-quarter thrust? Is it in the round and everyone is in three rows, or is everyone against the wall?

We arrived at what we did because of how people move through the play. A lot of the play is catching two parts of a conversation in two different segments, with characters leaving and coming back. We wanted to compress the playing space as much as possible. We based it around a circle (technically it was a hexagon or octagon). It's pretty steeply raked so people can see, with fresh wood, no paint, and silver bolts.

There's a whole permitting process for anything like that. You're basically changing the framework of [a venue's] Public Assembly permit. There was a pretty clear set of guidelines about what bleachers are and can be. We based it on what the city says a bleacher is. It's part of why I thought there were a lot of complaints about it being uncomfortable. I tell people, "Blame New York. Don't blame me!"

(© Doug Hamilton)

Spring Awakening

The Rosenthal Theater at Inner City Arts (2014); Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts (2015); Brooks Atkinson Theatre (2015)

Michael Arden's Deaf West Theater production of Spring Awakening premiered in 2014 at a small black box theater in Los Angeles. Laffrey consulted on the design of that production. After great acclaim, it transferred to the larger Wallis-Annenberg Center in Pasadena and Laffrey became the show’s scenic designer. His work moved to Broadway's Brooks Atkinson Theatre, where it runs through January 24.

(© Dane Laffrey)

Michael Arden is an old friend of mine. We were boarding school roommates at Interlochen Arts Academy. It started out as an incredibly catch-as-catch-can place, where we needed to do it in the simplest way possible. A lot of the [further] productions were built around [the original]: simple stuff, like how you can make a tree in the forest out of a bunch of bodies standing on a chair.

In moving to the Wallis-Annenberg Center, and hastily to the Brooks Atkinson, it really was about finding a container for it, something new and specific that functions in a certain way, but [still] fundamentally feels like a raw theatrical space. The research led us to looking at photos of performance spaces. This is most closely based on a contemporary performance space in Germany, an old boiler factory that was then converted into a music venue. It had all the functional things, like a reason for those catwalks to exist, which is important in how the staging was built. It's helpful when you have a character signing and a speaking character voicing for them, and you want to be able to focus on the signing person. It helps to put people on the fringes.

We adapted it one way for the Wallis, which is a wider, larger space, and then we reconfigured it again and made changes based on things we knew we needed. On Broadway, it's a lot taller and a lot less wide, which is more immediate.

(© Joan Marcus)