Biblical Wrath Rains Down on the Met Stage in Samson et Dalila

(© KenHoward/MetropolitanOpera)

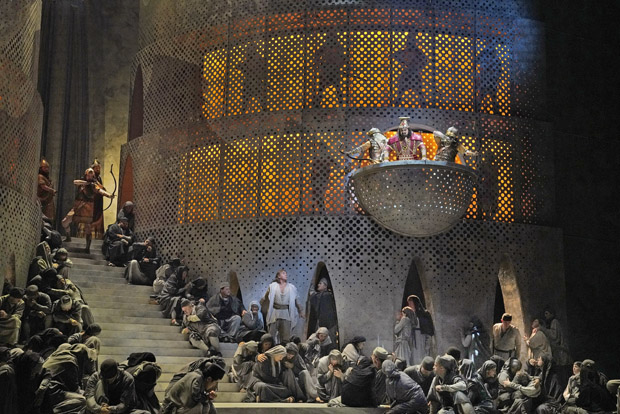

The Metropolitan Opera exists for operas like Samson et Dalila: Never is the world's grandest stage company better than when it is producing lavish spectacles with an exotically costumed cast of thousands. So it's a good sign when the curtain rises on the new production of Samson and we can see twin three-story towers occupied by torchbearers. Director Darko Tresnjak (Broadway's Anastasia) has opted for Cecil B. DeMille epic grandeur, something the pleading chorus, pounding drums, and frantic woodwinds of Camille Saint-Saëns's score demand. Unfortunately, the end result less resembles a film from the 20th century than it does an oil painting from the 19th — strikingly posed yet utterly static.

This is the fourth time the Met has opened its season with Samson et Dalila, and the 227th performance overall. Featuring music by Saint-Saëns and libretto by Ferdinand Lemaire, it tells the story from the biblical Book of Judges about the Israelite leader Samson (the suitably hirsute Roberto Alagna). He wants to end the subjugation of his people to the wicked Philistines, and he inspires them to action when he slays the cruel Satrap Abimélech (Elchin Azizov). Though he despises her people, he cannot help his love for the Philistine temptress Dalila (Elïna Garanča). She knows her power over him and conspires with the High Priest (a fearsome Laurent Naouri) to discover and eliminate the source of Samson's legendary strength.

(© KenHoward/MetropolitanOpera)

Tresnjak has reunited the design team behind Anastasia, with mostly happy results. Scenic designer Alexander Dodge makes good use of the stage's height with his towering, multilevel sets, while Donald Holder always seems to strike the right mood with his surprisingly intimate lighting. Linda Cho once again proves to be the MVP of team Tresnjak with her lavishly detailed costumes (Dalila's second-act dress, which unfolds like a blooming orchid, is particularly jaw-dropping).

The problems mostly derive from Tresnjak's lethargic staging, with performers hitting their marks but having little dramatic justification for their movements: A large group of Israelites politely cede the stage to Dalila and her Philistine maidens, as if they hadn't just embarked on a rebellion that has brought the two tribes into direct conflict. Much of Tresnjak's staging amounts to old-fashioned park-and-bark. Worse, the epic design recalls greater triumphs of the Met repertory, like Turandot and Aida, in which the chorus feels more legitimately human.

At least they sound excellent under the baton of Sir Mark Elder and chorus master Donald Palumbo. Precise diction allows for individual words and phrases to stand out, even during Saint-Saëns's more complex fugues. Elder's dynamic control extends to the orchestra in the form of well-articulated musical phrases, each ostinato perfectly clear.

Garanča gives a fine musical performance as Dalila, delivering a sensuous and bittersweet rendition of the opera's most enduring aria, "Mon coeur s'ouvre à ta voix." While she hits all the notes, she is less clear in her character's motivations. She doesn't seem to be the vengeful religious fanatic her words would make her out to be; in fact, we're never quite sure what is actually driving her. In the absence of a definite choice, there is no choice, to the detriment of her interactions with Alagna. There's a palpable disconnect between them, even as they cuddle before a cozy fire crackling in Dalila's cauldron. Later in the scene, she seems to tackle him in order to obtain his secrets, an awkward moment for all.

(© KenHoward/MetropolitanOpera)

Tresnjak's clearest vision is in the final scene, which takes place in the Philistine temple of Dagon, an open floor with three levels of mezzanine that looks an awful lot like the lobby of the Met during intermission. These proud Philistines drink and gossip, passively observing the scene before them: the famous Bacchanale. Austin McCormick, of the baroque-burlesque dance company Company XIV, choreographs this wild, orgiastic dance at first with disappointing dance-competition uniformity, but then, blessedly, with set-climbing abandon. It does the trick, just barely.

At the debut performance, Alagna wiped out on his high B-flat, meant to be Samson's clarion blast that causes the walls of this pagan temple to come tumbling down. But they never would have anyway as Tresnjak and Holder's vision instead offers the audience a burst of light that seems like a placeholder for a far more spectacular ending that never materializes. Some might see this moment as Alagna giving up on the production, but the truth is that it gave up on him, and Samson, long before.