What Is the Job of the Musical Director? Paul Gemignani Gives Us the Ins and Outs

The legendary conductor discusses his work and career with his biographer, Margaret Hall.

For every performer who steps into the spotlight as the curtain rises, there are hundreds of people working behind the scenes to make the magic of theater real. From dressers to spot-ops, house managers to stage door attendants, and everything in between, it truly takes a village to put on a show. This is the first in a series of articles designed to introduce you to the many unique theater professions you might not realize exist.

First up is the guiding hand of the music department, the musical director. From the very first audition to the final performance, they are the glue that holds a show together. When every other member of the creative team moves on to a new project, the musical director keeps the show alive throughout the entirety of its run. Every note of the score passes through their hands before it is presented onstage, and their guiding force can be the difference between an average performance and an edge-of-your-seat night at the theater.

To speak about this unique profession is Paul Gemignani, arguably the most influential musical director of the last 50 years. Conductor of more than 40 Broadway shows, including, most recently, Roundabout Theatre Company's revival of Kiss Me, Kate, Gemignani is also Stephen Sondheim's right-hand man, and his unique approach to the podium has inspired countless musicians to enter the profession.

Preorder Margaret Hall's Gemignani: Life and Lessons From Broadway and Beyond here (paid link).

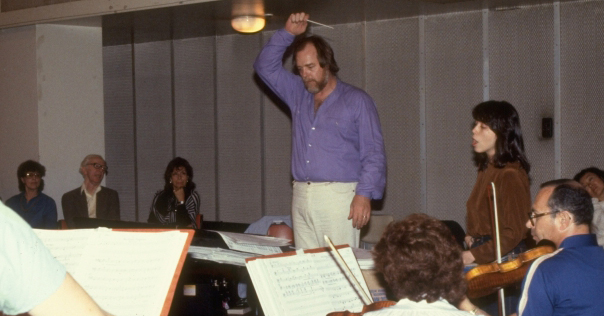

(© Martha Swope/New York Public Library)

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

How would you define the job of a musical director, and what is the difference between a musical director and a conductor?

[A musical director is] someone who unites the composer, the orchestrator, the director, the cast, and everybody else involved in the production. The actors need you every day, as does the stage manager, and the orchestrator and director need your opinion if they have any questions while creating. The composer needs an ally who is brave — you have to say the things someone else might be afraid to say. You're like the head adviser to the president. And you're a performer yourself.

A conductor is a music director. In the classical world, when you say "musical director," that means you're in charge of the orchestra. You're in charge of a bit more as a musical director in the theater. You audition the whole cast, you teach them the music, you sit in rehearsals and learn the show inside out. But basically, from a performance standpoint, there's no difference. You're the guy in the pit with a stick.

What drew you to becoming a music director?

Well, I wanted to be a conductor. I never did theater, ever. It was, to me, frivolous music, at that time in my life. You know how pigheaded we are when we're young. But then I saw Cabaret on Broadway and was blown away.

What enticed me about being a conductor in the first place was being able to help the musicians create the sound and the interpretation of a piece of music. I always thought it should be a collaborative art form. It never occurred to me that one was the maestro and the others were people playing instruments. It helped that I was a player first. I had played for so many conductors who didn't care what we felt about what we were doing. Never asked. "How would you play this phrase?" "How do you feel about this phrase?"

If you stop listening [to everyone], it's very dangerous. I think part of the job is seeing three seconds ahead, and the more you do it and the more you care, the better you get at it. That's what I mean about listening, because where they breathed the night before might not be where they breathe tonight. It's that kind of subtle difference that gives that in and out, wavy kind of glorious motion of a show that you can't put your finger right on.

You're very well known for your ability to bridge the gap between the pit and the stage. What's your secret?

I pay attention, for one. I think the secret is to memorize the score. It's something you should strive for, because it frees you up to pay attention. I don't believe the theater is a stagnant thing. Performance one is different than performance five is different than performance 15 is different than performance 120.

Of course, it's generally the same. An untrained eye can go in and see a show five times in a row and won't see any difference. But something might be a little faster, somebody may say a line a little slower, somebody gets a bigger laugh, something happens in the song, somebody takes a pause they didn't do before. You have to be paying attention. You can't have your head in the score to be effective, to actually be doing what you're supposed to be doing, which is directing the music.

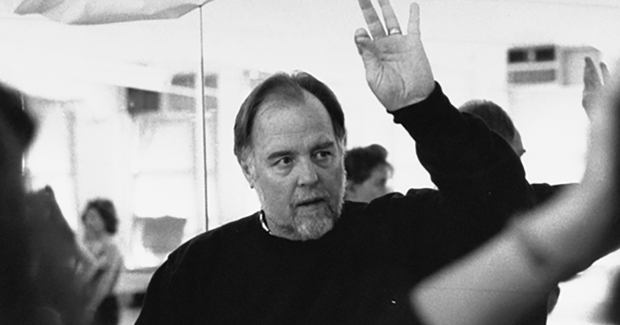

(© Martha Swope/New York Public Library)

What advice do you have for anyone who feels like there isn't room for them in the pit?

There's two things to think about. If you can dream it, you can do it. If this music is speaking to you in that special place, then you've gotta go and find out how to do it, and nobody can tell you you can't. And second… You want a chair in a band? Find out how to get it. Go talk to the conductor. Go talk to the trombone players. Say, "I'm just out of school, I want to play in the pit. I know I can't do it right now, but maybe I could sub, or maybe I could take a lesson from one of you guys?"

They were there once, they'll remember. And the ones that don't aren't worth it. Find somebody that'll say yes. They might not be able to help you as far as you want to go the first time — but take it. Any step's important when you're at the bottom of the staircase. I don't know too many musicians that would push you off if you actually talked to them. Don't talk to them on the phone, don't email them, don't Zoom them. Talk to them in person, because then they see your eyes and see who you are.

What record from your career do you think someone should listen to in order to understand what it is you do?

Jerome Robbins' Broadway. Either that, Sweeney Todd, or Crazy for You.

And if someone wanted to watch you conduct?

The My Favorite Broadway: The Love Songs concert for PBS.

What advice do you have to any early career musicians?

Just keep doing what you're doing. Play as much as you can and everything you can. Take every job, take every opportunity to play whatever you play, and have a good time. If you have a chance to play with a bunch of people who are way better than you, go ahead — how long will you be embarrassed? A day? What you'll learn you'll have for the rest of your life. Don't be afraid of any of that. Embarrassment doesn't mean anything. And if people tell you you can't do something, that's when you have to start thinking about how you're going to do it, The fact of the matter is I just kept going. Whatever I fell into I did, and I did the best I could. You only have one person to show: you. Period.

Preorder Margaret Hall's Gemignani: Life and Lessons from Broadway and Beyond here (paid link).