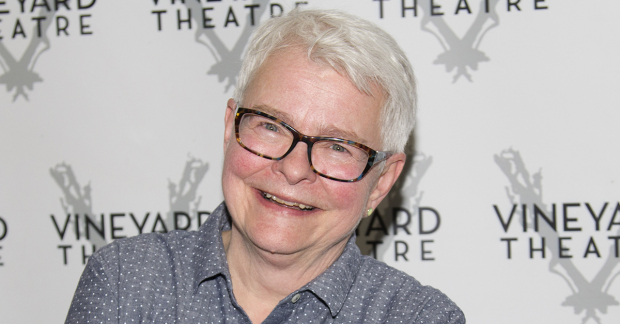

Paula Vogel: "Crisis Is Always an Opportunity for Change"

The Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright of ”How I Learned to Drive” discusses her newest venture, a streaming theater company called Bard at the Gate.

(© David Gordon)

When the theaters shut down on March 12, playwright Paula Vogel was deep into rehearsals for the long-awaited Broadway debut of her Pulitzer Prize-winning How I Learned to Drive at Manhattan Theatre Club. Like most artists, Vogel was bummed — "I was very depressed for about two weeks," she remembered, before she sprang into action.

Vogel, "68 and in a high-risk condition," she says, confronted the potentially deadly pandemic head-on by doing what she does best: making theater. She created Bard at the Gate, a startup series of play readings featuring works that she's always wanted to see live that have either been overlooked, never produced, or just deserving of a wider audience. The series has already seen readings of two of Vogel's bucket-list titles: Kermit Frazier's Kernel of Sanity and Meg Miroshnik's The Droll, with three more in this inaugural season to follow: Bulrusher by Eisa Davis (September 17), Dan LeFranc's Origin Story (October 7), and Christina Anderson's Good Goods (October 29).

The readings have given Vogel the energy to bound out of bed every day, as well as the opportunity to look at her role in the theater community, both as an artist and a mentor.

First thing's first. How I Learned to Drive was supposed to be running on Broadway this past spring. Is it still in the cards for whenever theaters reopen?

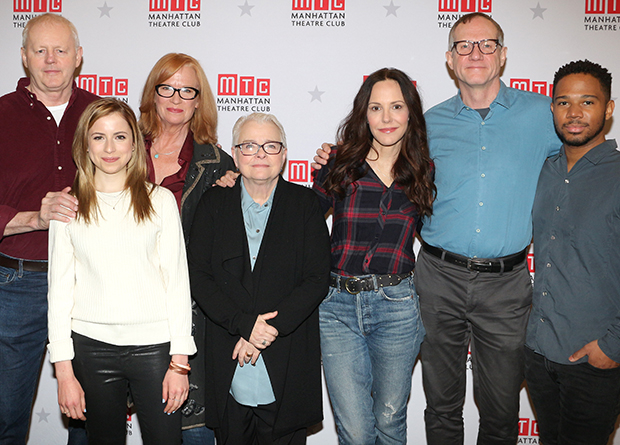

It's still in the cards, but I have to say, as a playwright — and I've done this for a long time — I don't believe anything is going to happen until I'm in the theater. Manhattan Theatre Club has renewed its commitment to the play, which is really lovely and extraordinary. And I do have to thank people like Daryl Roth, who really got behind this. The reason it all happened is because she couldn't stand the fact that How I Learned to Drive had never had a Broadway run.

(© David Gordon)

Did you have some kind of grieving process when theaters shut down and you realized that it wasn't happening this year, or have you been around long enough that you're able to say that it's just part of the business?

Well, I mean, the cheery thing about being 68 and in a high-risk condition [Vogel has asthma and diabetes] is that I thought, "Well, my number could be up," and that really puts things into perspective. I was very depressed for about two weeks, but I think I'm more depressed about — I've been depressed about our country for years. And then I thought of Bard at the Gate, and that gave me energy. So now I'm actually bounding out of bed. I'm looking forward to meeting all of these theater artists by Zoom and talking about the plays, and seeing them. The technology gives me the ability to do what I love and have always loved, which is just nurturing playwrights and new plays.

How did you come up with Bard at the Gate as a concept?

Well, there are two impulses. The first impulse was that I wanted to see Meg Miroshnik's The Droll. And then, as I started thinking about it, I talked to [publicist] Sam Rudy, and I said, "Look, there are a lot of plays that I'd love to see, either again or for the first time," and, you know, with Covid, you figure this could be your last hurrah. So for my last hurrah, I thought I'd like a) to share these plays that I may have seen a long time ago, or b) produce readings so I could see plays like Eisa Davis's Bulrusher. On top of the list was Kernel of Sanity by Kermit Frazer. I read that play in 1978 and had never seen it. So that's where the series came from. I'm doing it out of my own money, and it's always kind of interesting when our income, you know, is nil, but I've saved pennies for a rainy day and this is the rainy day. I thought it would give me pleasure and make me feel connected and, I hope, make other people feel connected to theater.

How did you settle on these plays you have scheduled? Do you just have a back pocket list of plays and pick from there?

I do have a list. I carry it around. I started talking to people about The Droll, and then I called up Kermit about Kernel. Dan LeFranc's play Origin Story is a legend. Origin Story was written as kind of a graphic novel. I have a frustration because we're not being adventurous enough in terms of creating hybrid forms, which, in the 40 years that I've run these programs, I see constantly. So how do you produce a graphic novel onstage? It's very akin to producing a radio show onstage. And radio shows work beautifully onstage because we have to participate in a different way as an audience.

Is this your first time producing?

I've always considered what I do producing. I have produced new plays for 40 years. And that involves making sure that the directing and playwriting teams are there, making sure the audition and casting process is good, making sure we advertise and get audience members, all of that on a tiny scale at Brown and then Yale. So, 40 times nine plays a year.

That's a lot of plays.

It's a lot of plays. And none of it is… There's a frustration that I think literary managers share with people who run MFA programs, which is, we see extraordinary things and can't convince our bosses to produce them. I've taken all of these scripts around from theater company to theater company, and Oskar Eustis or whoever I brought it to would pat me on the head and go, "Oh, that's nice." I would go to New York and say, "I just saw this play Nilo Cruz wrote in 48 hours called Dancing on Her Knees," or "There's this woman, Sarah Ruhl, you won't believe what she did on a hundred dollars," and they'd pat me on the head. They think that students are students, whereas I think of students as the next generation of my colleagues. I always say that the way that new plays get around the country… We're like monks smuggling out the Bible. People pass around Origin Story. It's known. People pass around Christina Anderson's plays and Eisa Davis's Bulrusher. It's not a tenable situation.

(© David Gordon)

Where do you see Bard at the Gate going after this initial run?

I can see doing one of these series every year, but I think it becomes part of the problem then. Because then what happens is, like every not-for-profit theater, it's curated by the taste of one person, and then I would become, in essence, a gatekeeper. If this does catch on, we could turn it into a not-for-profit that basically does development as fundraising for not-for-profit charities. Which I have to say, for all of us who are artists who have lost our jobs, the fact that we can do something that raises money to provide food or rent for artists or people who are out of work is extremely satisfying. What's really tugging at my heart right now is that one of the writers I would love to see more of is Dipika Guha. My difficulty is that I'm running out of money and that I love so many of her plays that I wasn't sure which to pick.

I had pitched Manhattan Theatre Club the idea of doing an online reading of How I Learned to Drive on what would have been its opening night, and they didn't seem interested. I presume everyone was afraid it would cannibalize audiences if the project comes back. Where do you think the industry goes from here, in terms of content and form and company structure?

Regarding How I Learned to Drive, I think everyone in the cast would gleefully do a Zoom, any format, just so we can work. Theater companies are running on this notion of "If we show 1,000 people a reading, it will take away 1,000 tickets," and that's not the way I think of theater. I think you see the Zoom and it excites you to see it live. Likewise, every single person I asked to do Bard at the Gate immediately said yes. So there's a difference of opinion in terms of how the arts economy works. Meanwhile, look at Germany. Their theater companies all produce videos and show them, so we are way far behind. I think it's because we believe so much in capitalism, that we stopped believing in art.

The good news is that there's a generational changeover, and this is going to be the very best thing for theater. Part of that is me being aware that my primary function has to be supporting younger artists so they hang in. It's not that I'm going to stop writing or stop being an artist, but at this point, we really have to think about the future of our field. I don't wish for crisis, but I think crisis is always an opportunity for change.

This is sort of the moment I feel like we've been training for. Think about Flint. The people who are saving that community are the people who live in that community. The same thing is true for us as artists. I have always been fixated on what artists do in times of huge crisis. You have to make your work.