Deaf Broadway Makes Strides for Deaf Audiences and Diverse Casts in Musical Theater During Shutdown

The new company has been producing shows like ”Sweeney Todd” and ”Les Mis” since the early days of the pandemic.

(courtesy of Deaf Broadway)

Kailyn Aaron-Lozano, a queer Afro-Latina woman, is Emmett in Legally Blonde. Gregor Lopes, a Brazilian-born queer man, is Marta in Company. Malik Paris, a gay Black man, is Janet in The Rocky Horror Show. Deaf Broadway is not only redefining access to Broadway musicals for Deaf theater fans, but offering up a model for nontraditional and diverse casting along the way.

This Thanksgiving, Deaf Broadway drops its sixth show, the legendary smash hit Les Misérables. Recorded alongside the 10th Anniversary Concert at Royal Albert Hall, it is performed entirely in ASL by Deaf talent drawn from across the country, more than half of whom are people of color.

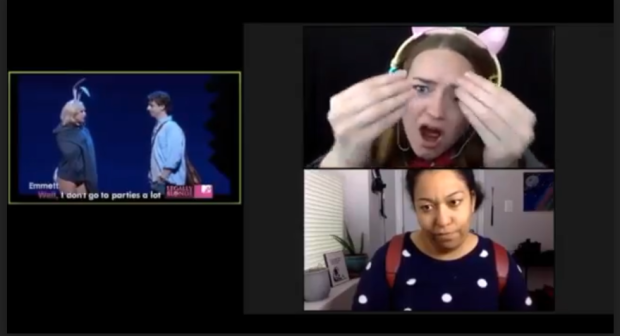

The company was born in the harshest early days of quarantine, when a group of Deaf and hearing friends held a Zoom watch party of Sweeney Todd's original Broadway production. As the group sang along together, some ASL users — including Deaf Broadway co-founder Garrett Zuercher — kept getting lost. When they asked hearing friends for clarification on certain lines or even whole numbers, Zuercher realized just how much the captioning wasn't getting across.

"A whole new world opened up, and it became clear that the best, most obvious way to make shows like this accessible to the Deaf Community was to provide visual language access," said Zuercher. "Only with ASL can the full nuance intended by the original creators finally be revealed for the Deaf community to understand, appreciate, and enjoy."

Zuercher teamed up with technical director and editor Kimberly Hale to create an all-ASL online reading of Sweeney Todd, performed by and for the Deaf to be watched alongside video of the original production. The final product spread quickly within the Deaf community, and was an immediate smash. Requests for "More!" poured in from fans, educators and theater access organizations. From the forced limitations of quarantine, a path to even greater access had been born.

"ASL is a conceptual language," said co-founder Miriam Rochford, who has stage-managed every Deaf Broadway production. Rochford is hearing, and would help to explain certain meanings that captions could not capture.

(courtesy of Deaf Broadway)

"With Sweeney Todd, someone would sign 'Priest' or 'pipin hot,' and it'd be like, well actually that concept is not what he means," recalled Rochford. "It's actually a play on words, or he's turning the concept on its head."

"[Captions may] omit lines entirely, or fail to indicate what is being overlapped, and almost never indicate who is speaking," added Hale. "Hearing people often take for granted all of the incidental information they get from their ears." Hale relabels and clarifies each line ahead of a recording, adding character names and specifying overlapping dialogue.

The company quickly followed up with Into the Woods and Company, but as awareness of their work grew, copyright issues reared their heads. While Stephen Sondheim's lawyer quickly granted blanket permission ("nothing would make Stephen Sondheim happier than to know that you were doing this work," Rochford quotes him, still in disbelief), the process for other shows took longer. Producer Hal Luftig did get MTV and his fellow producers on board for Legally Blonde, which was released in May. But a forced break followed as other rights negotiations stalled.

Les Misérables was actually recorded in April, but only in September did a personal connection to producer Cameron Mackintosh come through. In the interim came Rocky Horror, a collaboration with ASL Rocky NYC, who performed live ASL productions of Rocky Horror in the before times.

Hale painstakingly added character names to nearly every line of Les Mis, a busy and chaotic show which proved Deaf Broadway's most challenging task so far. "'We had to basically go through the show line by line and explain who is singing what, especially when alternating between solos and ensemble," said Zuercher.

One of the most challenging songs, ironically, was "Do You Hear the People Sing?" "We don't," laughed Zuercher. "We can't hear when it's just one voice, versus many. So we have to notate which are ensemble lines and which are solos and by whom, so that the right person will jump in. There were a lot of mistaken assumptions by the cast that we had to fix."

Deaf Broadway is still figuring out future plans. A holiday special is in the works, and early talks are underway for other collaborations. As it looks forward, Deaf Broadway will continue expanding its work in accessibility and diversity, casting as wide a net as possible for its talent.

"When we let our performers inspire and lead us, magic happens," said Zuercher. "The most important thing here is that we're all having fun doing what we love to do."'