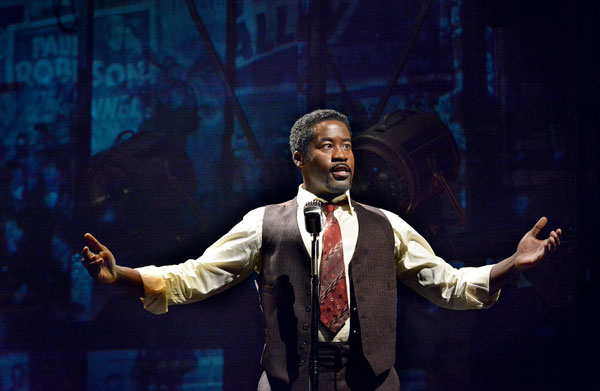

African-American Icon Paul Robeson Is Inhabited by Daniel Beaty in The Tallest Tree in the Forest

Beaty delves into the man behind “Ol’ Man River” in his latest solo show at Washington, D.C.’s Arena Stage.

Daniel Beaty returns to Washington, D.C.’s Arena Stage for the third time with his new solo show, The Tallest Tree in the Forest, which chronicles the controversial life and career of legendary African-American performer Paul Robeson. Though Beaty takes on the daunting task of portraying over 40 characters, he is no stranger to a hefty workload, having taken on just as many personas in his last Arena Stage production, Emergency. TheaterMania spoke with the ambitious actor/singer/writer, whose passion for tackling racial and social issues has given him the energy to delve into the many historical figures who shaped Robeson’s life. Beaty shared his thoughts on the famed “Ol’ Man River” crooner as a political figure, his penchant for D.C. audiences, and his own motivations as an artistic activist.

(© Don Ipock)

What sparked your interest in developing a piece about the life of Paul Robeson?

I always loved the Negro spiritual and he has some of the most phenomenal recordings of [them]. I became serious about the man behind the voice when I discovered the breadth of his accomplishments. He was a scholar, a lawyer, an athlete, a star of stage and screen, an activist for workers and people of color across the world — I felt determined to do what I could to tell this story creatively so that more people could know about who he was and what he contributed.

His life and career were very controversial. Do you present both the positive and negative sides of his character?

People say he was a traitor because of suspicions of communism. As a playwright, I know that I cannot create a play that’s hero worship. I have to show a fully dimensional human being and every human being has flaws and often it’s through a character’s contradictions that their heroism emerges. Robeson went on record saying he was not a communist, so the real question I’m asking is, what was it about the character of this man that caused him to choose his activism at the height of his international fame as an artist?

What is it like performing this play in the country’s political center?

I love D.C. audiences. I do believe, because so many people in D.C. are actively engaged in the social political discourse, that this is a good town for my work. I love the way the audience leans in and listens [to] these types of conversations.

Do you feel art has the responsibility to make a political statement?

I don’t feel that all art needs to be political but I certainly feel that art has the potential to participate in the social discourse, and even more so, artists have the potential to participate in those issues that they find most urgent. I in particular feel that the issues of the world are so urgent that I have a hard time focusing my creative energies on works that I don’t feel in some way are responding to issues of urgency.

What do you hope audiences leave understanding about Robeson?

I titled the play The Tallest Tree in the Forest after a quote from Mary McLeod Bethune. Robeson, in his time, was the most well-known black figure in the world and he achieved tremendous heights not only as an artist but as a thinker and participant in the social political discourse. He sat with leaders of nations all over the world and that gave him a unique purview. He indeed was the tallest tree in the forest. And all of these factors contributed to his perspective, his character, and ultimately the choices he made. I certainly mention some of his faults — his humanity — in the play, but my greatest hope is they have an understanding of the complexity of his character and the time in which he lived.

One of your earlier plays, Emergency, is also a solo show in which you take on dozens of characters. What is it about that structure that so strongly appeals to you?

I think it’s because it references some of those original storytelling forms of the African griot who chronicled the passions and the history of his community through his job as a storyteller. Whether it was sitting by the campfire or at a special day for the community, the griot would stand before the community as an individual and create a whole world of a narrative and make it real and alive for an audience. I think there’s a special alchemy and magic that can happen in that form.

Do you ever get lonely doing these solo shows?

I call the works like this “solo plays” but truly there’s nothing solo about it. The sound, the lights, the projections, the set, the stage manager who’s calling the show — they’re all my scene partners. And also the audience. Sometimes there are moments of direct address, sometimes they’re paying witness to characters in conversation with each other, but their breathing, their laughter, their tears, their gasps — these are all my scene partners. So I don’t think of it in terms of being solo or being lonely. I think of it in terms of playing a role in the larger community that makes theater.

Paul Robeson’s epitaph says the following: "The artist must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative." Do you agree with that statement?

I absolutely do agree with that statement for myself, and I hope it for people who would aspire to be artists. I think to have the privilege of standing before people is a huge gift. We only have careers because people have decided that we have something that they want to hear, that they want to support, that they want to show up for, and I believe the gift we give back is participation in whatever issues we find urgent. Some people say artists [and] entertainers, have no business participating in social-political issues. I say we have an absolute opportunity and responsibility to participate, those of us who work in the creative arts have special and particular gifts that have the ability to remind us of our humanity and in some ways expand our humanity.