Mlima's Tale Navigates the Illicit Ivory Trade

Lynn Nottage return to the Public Theater with a tale of two tusks.

(© Joan Marcus)

Greed is the fuel that powers a market economy, while lies lubricate the engine. That's crystal clear in Lynn Nottage's unrelenting machine of a play, Mlima's Tale, now making its world premiere at the Public Theater. Directed by Jo Bonney, this assembly-line presentation of the ivory trade shows us the whole process, from majestic elephant to decorative carving. Remarkably, Nottage enchants her machine with real emotional stakes: Audiences won't soon forget the anguished wail of its title character, an African bull elephant described as "one of the last of the big tuskers in Kenya."

We only really get to hear from Mlima (Sahr Ngaujah) in the first scene, which shows the last moments of his life. Having tracked him for 40 days through a Kenyan national park, two Somali poachers (Jojo Gonzalez and Ito Aghayere) kill him and hack off his tusks. They hope to sell the tusks to the local chief of police (Kevin Mambo) for 50,000 shillings (around $500), but he only pays them half that, insisting that he's doing them a favor since Mlima was a beloved symbol of Kenya's wildlife and the authorities will be looking for these illegal goods. Of course, he knows there is a lot more money to be made outside of Kenya: Eventually, Mlima's tusks will fetch the staggering price of ¥7,000,000 (roughly $1.1 million) in China, where demand for ivory is the highest. With each scene depicting a point in that journey, Nottage breaks down the value added, which turns out to be a little bit of artistry and a whole lot of bribery.

(© Joan Marcus)

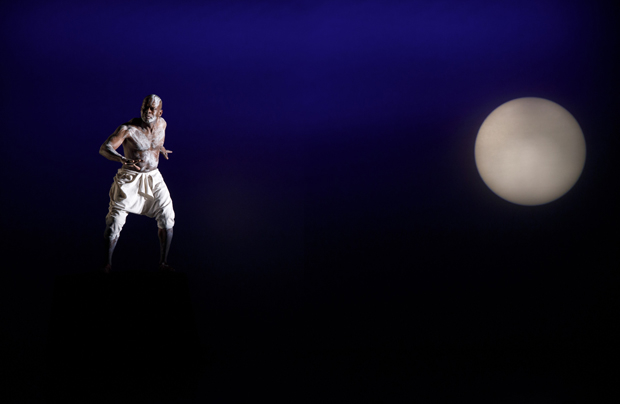

Ngaujah stands silently and imposingly in the background of many of these scenes as his traders haggle. The image of a partially clad black man being sold across the waves conjures a painful history. Nottage and Bonney suggest that the amoral "rational" self-interest that drove the slave trade then still drives the ivory trade today.

In many ways, Mlima's Tale is a sharper critique of capitalism than Nottage's last play, Sweat, about the devastating effects of Rust Belt deindustrialization. While Sweat sensitively portrayed capitalism's victims, Mlima's Tale exposes the entire system (and in almost half the time). Nottage has cleverly borrowed the format of Arthur Schnitzler's La Ronde, which depicts a chain of sexual encounters. Like La Ronde, the characters in Mlima's Tale span the class spectrum, but instead of sex, they're looking for ivory and cash.

With just four actors, Mlima's Tale is a model of efficiency. The three players (Aghayere, Gonzalez, and Mambo) portray every human, using subtle physicality and muted accents to distinguish roles without slipping into caricature (Jennifer Moeller's evocative costumes also do this). As the deceased elephant, Ngaujah stalks them all like a spectral pachyderm. His spiritual enormity is rendered most powerfully through composer and musician Justin Hicks, who sits outside of the proscenium and gives voice to Mlima. As amplified by sound designer Darron L West, the voice sometimes causes the floor to shake, as if an elephant were hurtling toward us.

(© Joan Marcus)

Riccardo Hernandez's minimalist set facilitates a play in which no two scenes take place in the same location, while elegant floating screens provide for speedy transitions. Onto these screens, Bonney and Nottage project African proverbs like "No one tests the depth of the river with both feet" and "Even the night has ears." Moralizing and vaguely opaque, these titles land like Brechtian fortune cookies. They are also ultimately unnecessary, since Nottage's scenes already say everything about how culpability spreads like a virus to all who touch Mlima's tusks.

Bonney must have surely been thinking something along those lines when she staged Ngaujah to smear each of his captors with white paint at the moment of transaction (haunting work by Cookie Jordan). This mark of Cain visualizes the truth of the matter as their words furiously dispute complicity: Several times throughout the play, characters ask for assurances that the ivory was extracted legally, that no animals were really harmed, and that anyone who does harm animals will be punished. Essentially, they are asking to be deceived.

(© Joan Marcus)

It is telling that the people who actually did the dirty work of killing Mlima get a measly $250, while his final possessor makes off with a status symbol, a clean conscience, and seemingly all the money in the world. Eighty straight minutes of searing brilliance, Mlima's Tale makes a strong argument for plausible deniability as a luxury far greater than ivory, afforded to only the most privileged. The rest of us will have to make do with the little lies we use to convince ourselves that we're not really aiding and abetting such grinding exploitation.