Twenty-Five Years After Opening, Maury Yeston and Victoria Clark Recall Their Titanic Experiences

Yeston’s musical, written with Peter Stone, opened at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre on April 23, 1997.

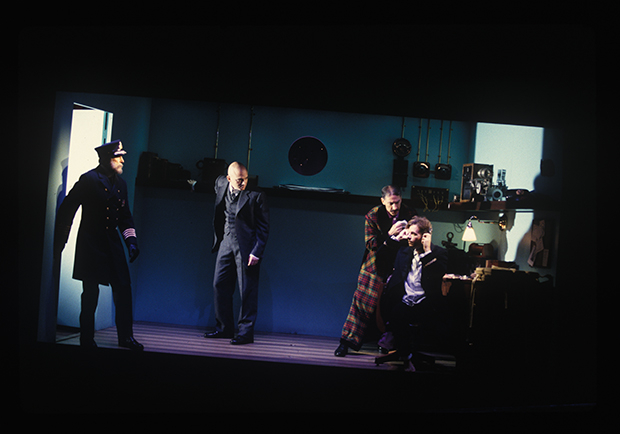

(© Joan Marcus)

Twenty-five years ago this month, one of the more unlikely musicals of our generation set sail for Broadway. The main character wasn't any of the dozens of characters that populated the show, it was a ship. A ship believed to be unsinkable. You all know how that turned out.

The unlikely success of Maury Yeston and Peter Stone's Titanic, which opened April 23, 1997 at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre, is even less likely when you consider the icebergs in its own path. Unlike in real life, this Titanic actually couldn't sink, and it took until the eleventh hour to figure out why. Yet despite mixed-to-negative reviews, this massive production not only went on to win five Tony Awards, including Best Musical, but now lives comfortably as a staple of the contemporary theatrical repertoire.

But how did they build Titanic?

It all started, composer-lyricist Yeston says, in the 1980s, as he looked back on the events of the 20th Century and began realizing that all the major accomplishments of the era started out, much like a musical, as a glimmer in someone's eye. "The obvious story is that Titanic is a tragedy, but the point was not what happened to it, but why it was created. It's a story about our dreams [against the challenges of adversity]. The dreams of the immigrants who wanted a new life in America, like my grandparents. The dream of a ship that couldn't sink."

As Yeston began digging into his idea, the Challenger space shuttle blew up just after takeoff in 1986. Not unlike the iceberg breaching the watertight compartments of the Titanic, the Challenger disaster was caused by the failure of two seals designed to prevent fuel leaks. "I realized we were still living this story," Yeston remembers, "and that was it." He eventually reached out to a good friend of his, book writer Peter Stone (1930-2003), to help shape the material. "Because, of course, the man who convinced you that the Founding Fathers weren't going to sign the Declaration of Independence would be just the right guy to convince you that the ship wasn't going to sink."

But how do you actually raise the stakes when everyone knows that by the end, a pleasure cruise will turn into one of the most infamous maritime disasters in history? "The first thing I discovered," Yeston continues, "was that at the beginning of the show, a guy kisses his girlfriend goodbye and says, 'I'll see you in two weeks.' Suddenly, everybody realizes that he doesn't know what's going to happen. None of them know. And suddenly, you're worried about them. That was the way into it." The two men wrote and wrote, often meeting at the same restaurant in Manhattan. They were so deep in the work, Yeston adds, that they didn't even realize when their usual spot changed ownership and the cuisine shifted from Chinese to Indian.

(© Joan Marcus)

However, even in the pre-social media age, word of mouth can kill you before you even start. "Watch 'Em Sing, Watch 'Em Dance, Watch 'Em Drown" was the headline Yeston recalls most fondly, courtesy of the gossip columns. But they plowed on. They found a director in British-born Richard Jones after Yeston auditioned the material for the likes of Trevor Nunn, Franco Zeffirelli, Mike Nichols, and Harold Prince (who told Yeston to direct the show himself). They found lead producers in Michael David and Joop van den Ende's conglomerate Dodger Endemol Theatrical Productions. They got the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre, prime real estate on 46th Street in Times Square, and a cast that included a who's who of relative newcomers including Michael Cerveris, Brian d'Arcy James, and Victoria Clark.

"I would kind of giggle the whole time," Clark remembers. "I couldn't see how this was going to work, you know? There was part of me that, every day from the time I was cast to when we opened, was expecting a phone call saying don't come in because it fell apart. And that call never came. But there was this sense of 'Is this really going happen?' What saved us in the company was that Richard only cast people who were fun to be around, who were funny, incredibly skilled as actors and singers, and were just really great people. We were determined to enjoy the experience no matter what, and we committed to it."

And there was a lot to commit to. "We did a million versions of most of the songs," Clark adds. "We'd change the order. We gained material and lost material. Everyone's parts kept going up and down, and down. Because it was about the ship. There were some really incredible performances in that show and none of us were nominated for any awards because, as we were all told and as we sort of bought into, the star of the show is the ship."

By everyone's estimation, building that ship (which you never quite saw, given the more abstract nature of Jones's production) took forever. "The amount of tech rehearsal was intense," Clark says. And while she doesn't remember the set ever completely breaking, in previews, it never quite worked the way it should. "If you saw the show, you probably remember this. At one point, there was a piano that slid from one side of the deck to the other, and it was a hydraulic mechanism that had to tilt up and down and do a lot of different angles. And it took a long time for the computer and the mechanism to work together to create the effect."

Pretty much nightly, the show would have to be stopped right as it was getting to the point that everyone had come to see — the sinking. "We were so nervous that the audience would walk out, and some of them did. We couldn't just leave them sitting in the dark, so some of us with comedy backgrounds would go out and be real with them. [Cast member] Michael Mulheren would come out and tell jokes."

At the same time, Yeston and Stone had bigger fish to fry. Not only were the technical aspects not working as they should, but the written elements weren't either. "The problem was the entire lifeboat sequence, which is the end of the show," Yeston recalls. "We tell several stories simultaneously, and now everybody was going to be on stage. In rehearsal, we had a panoply of conversations. Upstage left, two lines of dialogue between the stoker and the telegrapher. Center stage, the captain would be barking orders at the first mate. And they'd switch very quickly. In rehearsal, it was complicated, but interesting. When we got on stage, everything came out of the same speakers and there was no directionality in where the sound was coming from. You couldn't understand anything that was going on. We had spent so much time on it, and it was just endless. No one really knew what to do. Peter Stone was up against the only thing that a book writer can do, which was rewrite, but it wasn't about what was written. It was that we weren't able to get it across the orchestra pit in a comprehensible way. That's a huge sequence, the end of the show and the resolution, and we were lost."

With only a few weeks before opening night, the writers began to lick their wounds. "Maybe the critics will say it's a shame that they couldn't bring it all together, but the songs will get a nice mention," Yeston remembers thinking. And then, one night after a long preview, it hit him in the shower. "When my son was growing up, he asked me who Richard Nixon was. How do you tell a child that Richard Nixon is a bad man?" That was it. "We had to find a way of explaining what was happening as if you were speaking to a child. And we did have a kid on stage. So what if I take one of the mothers, and she's putting a yellow life vest on him, and she sings 'You and I are getting in the lifeboat/father will be staying here a while.' And the kid would rush and grab his father's knees, and the father would take his hand and push him back to his mother. I started crying, and I went to the piano, and everything we had wanted spoken, we had sung. 'We'll Meet Tomorrow' is the same dramatic discovery as the entire show. You're not going to meet tomorrow. I knew it was going to work.'" It went into the show the next night, and the house came down.

The cast knew it worked when they started seeing the stagehands crying. "We had been getting polite applause and saw people walking up the aisle," Clark notes, "but then we lined up for the curtain call and the crew was weeping. These big guys in the flies running the scenery were so exhausted. Everybody had been making jokes about the sinking show. And their faces were all sorts of red and blotchy. We all looked at each other and were like, 'Oh.'"

Reviews of Titanic were mixed. More on the negative side of mixed. "Titanic…doesn't sink," Ben Brantley wrote in The New York Times. "Unfortunately, that is also probably the most exciting thing that can be said about it." There were three things that shifted the tide, starting with the sterling endorsement of Rosie O'Donnell, who had cast members perform on her talk show twice. "I think within two weeks of opening, we were on her show," Clark says, "and after that, the ticket sales bumped up." That June, it cleaned up at the Tony Awards, winning all five trophies that it was up for, including Best Musical, Best Book, and Best Score. Finally, that November, James Cameron's completely unrelated cinematic epic, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet, was released in cinemas and caused an immediate sensation. The musical ended up running for two years and 804 performances.

"We were very lucky our supporters were so vocal," Clark says. "There was no out-of-town tryout. We did this all under the public eye. If we had started in Boston or Philly or Seattle, somewhere else, we could have worked out all this stuff out of town. It was so brave of Peter and Maury to just be like 'We're going to do this,' as people would come just to see how much of a disaster it was. But they would hear that the music was incredible or that the book was interesting or that the visual images were stunning, and they realized it wasn't a joke. You wouldn't know that unless you came. And then word of mouth started to spread. We were just very, very lucky."

One of the most frequent questions Yeston seems to receive these days is "When will Titanic be back on Broadway?" Two major productions have been lapping at the shores of New York City over the last decade, a revival from London's Southwark Playhouse that perpetually tours the British Isles, and more recently, a version first staged at Signature Theatre in Washington, D.C. and has since become a hit in Seoul, South Korea. But as Yeston puts it rather piquantly, it's not about interest, "It's about who gets a slot."

His biggest delight, over the 25-year lifetime of the show, was watching it performed in Belfast, where the Titanic was built, on the 100th anniversary of the sinking in 2012. "They started the show 100 years to the minute that the ship hit the iceberg, and before the overture, a single violinist played 'Nearer My God to Thee.' It was unbelievably thrilling."

But Yeston is just as excited by seeing how Titanic has become part of the musical theater canon around the world, which is way more of a hallmark of success than wondering whether Broadway will ever beckon again. "The script is great, the music tells a story with just a piano, and there are a zillion roles, so anybody could do it, and they do it all the time," Yeston concludes. "It's touring the U.K., it did a tour of China, it was in Tokyo, it was just in Budapest. It's in high schools, it's in operatic societies. It's just forever everywhere." Not bad for something that started out as a dream.

(© Joan Marcus)