The Life and Death of Marina Abramović

An epic collaboration between an avant-garde theater director and a world-famous performance artist finds its strongest moments in the traditional conveyance of pathos.

(© Joan Marcus)

Robert Wilson has single-handedly kept Ben Nye Cosmetics in business for decades with his bulk orders of “Clown White.” Pale-white faces, slow and deliberate movement, and sharp angles have been a part of Wilson’s instantly recognizable style for the last 40 years. The legendary experimental-theater director and frequent Lady Gaga collaborator has turned his idiosyncratic gaze on yet another fierce woman: performance artist Marina Abramović. Wilson’s latest theater piece, The Life and Death of Marina Abramović, is making its U.S. premiere at the Park Avenue Armory. This bio-musical starring Abramović herself is a beautifully constructed and visually arresting exercise in self-indulgence.

Really, after years of self torture in pursuit of art, hasn’t Abramović earned the right to indulge? The famously masochistic performance artist made a name for herself in the ’70s with pieces like Rhythm 0 in which she surrendered her body to the will of her audience for several hours, often to terrifying results. New Yorkers most recently encountered her in the 2010 MoMA retrospective The Artist is Present, during which she sat for a total of 736 hours (From March 14 to May 31) and made eye contact with whoever sat in the chair opposite her.

One would expect a marathon from the collaboration of two artists infamous for their endurance. (Wilson’s KA MOUNTAIN AND GUARDenia TERRACE lasted seven days on a mountaintop in Iran, while Abramović lived in a glass box without food for twelve consecutive days for her 2002 piece The House with the Ocean View.) Happily, The Life and Death of Marina Abramović speeds by at a brisk (for them) 160 minutes.

For much of the show Willem Dafoe sits in a downstage square dominated by large file boxes. Wearing a military uniform, his red hair teased toward the heavens, he resembles David Bowie at the height of his Nazi phase. He serves as the narrator for the proceedings, reading details of Abramović’s life from the surrounding files, obviously meant to evoke the secret police of Tito’s Yugoslavia, where Abramović was born.

This constant reminder of the historical reasons for the Eastern European queasiness with sharing personal anecdotes (as opposed to Americans who more often than not tend to overshare…let’s call it the “Oprah Syndrome”) raises the stakes for the event. A laundry list of life events is illuminated by performance. The cruelty of Abramović’s mother (played at first by Abramović, until she transitions into playing herself) comes into full focus. We begin to dread the echoing footsteps of the Maria Callas-lookalike with the stern face and habitually crossed arms. A man with a snake (yes, it’s real) wrapped around his body walks slowly across the stage with zenlike serenity, giving a sense of calmness in ever-present danger, a recurring theme in Abramović’s life.

These moments of tension are relieved by the soulful and otherworldly voice of Antony (of the band Antony and the Johnsons). When he sings Baby Dee’s “Snowy Angel,” you can feel the room cool, as Abramović escapes the molten volcano that is her childhood home for the refuge of a hospital (she was diagnosed as a child with hemophilia).

The first act concludes with the repetitive traditional Balkan call-and-response “Oj jabuko zeleniko,” led by Svetlana Spajić. As uniformed cast members march in from the sides, the tone becomes increasingly martial, culminating with Abramović riding in on a wooden horse bearing a white flag of surrender. Dafoe and others shout her Manifesto through megaphones as the music becomes louder and louder, prompting the more sensitive members of the audience to hold their ears.

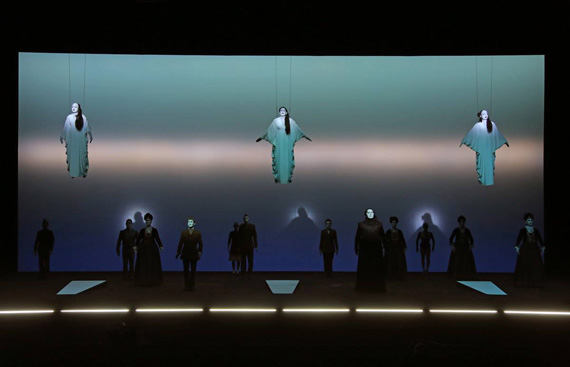

Listening to the repetition of the passage, “An artist should not make themselves into an idol,” I was struck with the incongruity of these words to the surrounding event. Abramović’s martyrdom is very much the central image of this memorial for a living person, which begins with three dead Abramovićs lying in state and ends with the same three women shrouded in white and suspended over the stage, the real Abramović in the center with her arms extended like the Crucifixion of Christ or the Assumption of Mary. At one point a crawling Dafoe sings, “Why must you suffer like Christ?” while Abramović lies sprawled out on a platform like an Egyptian queen in a feathery red dress.

An artist who uses her own body as her medium must necessarily accept a certain cult of personality and this piece seems to embrace that fact, with more than a hint of irony. Curiously, the most captivating moments are the quotidian and commonplace details of Abramović’s life: the loneliness of her life on tour, her desire to find happiness in a partner (like so many of us), and the revelation that the man to whom she dedicated this performance (her life and death) never even bothered to show up. Abramović sits on the stage stoically listening to Dafoe read these very recent devastations before hundreds of spectators. In terms of exposure to pain, it is a feat that rivals her earlier work.