Secrets of Pleasurable Theatergoing (Part II)

This is part II of Michael Feingold's latest "Thinking About Theater" column.

Click here to read part I.

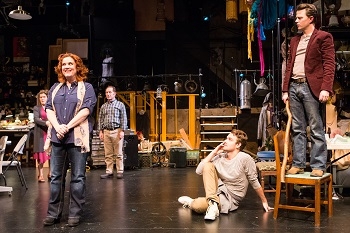

(© Joan Marcus)

Once you’ve shaken off the tyranny of star names, you find many elements that can help theatergoers choose their pleasures. Within the Internet’s information overload, data of actual helpfulness can be found. Following up on last week’s column, let me offer a few more rules you might usefully apply — with the caveat that I often break them myself.

2. Titles can be telling.

A play’s title is a clue, though not always a literal one, to its essence: Hamlet is about Hamlet; Betrayal is about betrayal. Add a few facts, and a title’s a clarifier: A Man’s World, written by a woman in 1910, was playing in a small theater downtown, while No Man's Land, which dates from 1974, was starting previews on Broadway, with stars. You didn’t need to know anything about playwrights Rachel Crothers and Harold Pinter to guess which play would interest you.

Yet titles alone can mislead. Though I normally avoid Beth Henley plays, I almost went to see The New Group’s The Jacksonian, until I learned it was about a motel in Mississippi, and not about a follower of Old Hickory. And I suspect that a few oldsters may turn up at the Pearl this month expecting Terrence McNally’s new And Away We Go to be either an early draft of Oklahoma! or a bio-drama about Jackie Gleason.

(© Al Foote III)

3. Don’t believe what “everybody” says.

“Everybody,” of course, doesn’t exist. Back when more New Yorkers enjoyed and could afford weekly theatergoing, “word of mouth” was a reality: People’s friends and neighbors talked about which shows they had or hadn’t enjoyed. Today that mode of opinion has gone virtual — but bloggers, chatterati, and Facebook friends often aren’t people you know well enough to weigh the value their opinions. Also, these days "everybody" usually means an online reviewer, most often in The New York Times. The Times Theater section has some intelligent and well-qualified contributors, but that doesn’t keep them from having, like all theater journalists, their favorites, blind spots, agendas, and limitations. Discovering what those are – which regrettably can only occur through bitter letdowns at overpraised shows – is part of the process that molds a wise theatergoer.

4. Cherish your prejudices — and violate them.

Beth Henley, mentioned above, is by no means the only playwright whose work I consciously avoid. Like Ko-Ko in The Mikado and like most of my colleagues, I’ve got a little list, containing at least a dozen shun-when-possible writers, of both genders, all ages, and various ethnic groups. As I hate unfairness, I’ve made it a principle to fight my prejudice by sampling their work at least once in every three or four plays. And happily, I sometimes find myself revising my opinion upward.

I’ve got lists of actors and directors, too, but artists in these categories can seem to change extensively from one production to the next. Actor X, who casts a special glow over playwright M’s work, inexplicably turns into granite-faced stolidity when handed a script by playwright S. Director D can get a brilliant, coruscating performance from actress L while making actress Y look like an affectless stick. Every production brings a different set of variables. Discovering unexpected facets of an artist’s talent is built into the theater’s joy; along with it comes the risk of watching that talent misfire.

5. Watch for the red flags of terminology.

For me, one benefit of the Internet age has been the ability to click “delete” without reading an entire e-mailed press release. Unless there are mitigating factors, when I spot certain key words in a message’s heading, click, it goes. My warning list includes “interactive,” its bratty nephew “immersive,” “multimedia”; “installation”; “site-specific”; and that most misappropriated of theoretical terms, “deconstructive.” Some people enjoy all these phenomena, even finding them significant; for me they merely underscore the difference between theatergoing and attending a county fair. Not that I object to county fairs, per se — they just aren’t theater.

This rubric holds many exceptions. Artists who know what they’re doing can turn any technique to good theatrical purpose. Works in all these categories have powerfully enriched my artistic life. But much depends on context, personnel, and intentions: Two directors, proceeding from exactly the same principles, will not produce identical results. If they could, it would be the best argument against those principles. The most disheartening aspect of deconstruction has been how quickly all its devices have hardened into clichés.

6. Be tempted — sometimes.

The show that sounds perfect for you in a brief description may or may not turn out to be so in reality. Conversely, the work that sounds preposterously outré can be an unexpected delight. The instinct to know when to skip the obvious and plunge into the wackola needs nurturing; you won’t learn it overnight.

One of my happiest theatrical memories came via a press release saying, “This is a play about the grim future, and all the beauty that will soon disappear. It is based on old Hungarian language records.” That was Maria Irene Fornes’s The Danube — a masterpiece that I wish somebody would revive. Then there was a press rep’s phone call that asked, plaintively, “Would you be interested in reviewing a performance of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique by abstract puppets in a fish tank?” That introduced me to the uncanny world of Basil Twist. Not every invite to the outer lunacy will prove as artistically fruitful as these. Train your instinct and trust your luck.

7. Be sure you’re right — then change your views.

“If you don’t like an Aries,” say astrology buffs, “wait fifteen minutes.” I don’t know if those born under Aries are always changeable, but I do know that opinions, including mine, often are. What I think of a show when I get home won’t necessarily be what I think of it two months or twenty years later. Our constantly changing world alters your view of your recollected past. Some plays remain simply what they are; the better ones often surprise you, when they return, by seeming so fresh and different.

I’ve found that, frequently, the play that annoys me at first encounter is the one that sticks with me. I don’t mean the junk by sensationalist writers who set out intending to annoy. They rarely offer the complex values that make the great annoying masterpieces last: Measure for Measure, Major Barbara, Hedda Gabler. The more trivial annoyances fade from memory; the plays you can’t shake off, even in dislike, become lasting friends. You add them to the unshakably great experiences that give the theater meaning for you. And that, perhaps, is the ultimate secret to theatergoing: Whether you realize it at first, or not, you have an idea of what the theater means. You return to it hoping to have that idea fulfilled. Every show offers new expectations, raising renewed hopes of that fulfillment.

Michael Feingold's next two-part "Thinking About Theater" column will appear on consecutive Fridays December 13 and December 20.