Paris Is Where Dreams Go to Die

(© Ahron R. Foster)

It's easy to blame the Internet for the "disruption" of so many livelihoods in transportation, the media, and retail. But the latter was already a pretty awful way to make a living even before most Americans logged on, as Eboni Booth brutally shows in her beguiling new play Paris at Atlantic Stage 2. It's not about the city of lights. Rather, it is set in a big box store called "Berry's" in the fictional town of Paris, Vermont, circa 1995.

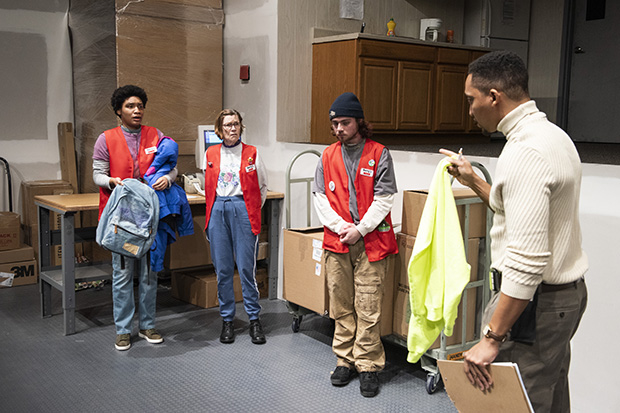

Berry's is as unglamorous a destination as one can imagine, and David Zinn has imagined it to be oppressively gray in his two-tier set, which depicts a stocking room and a joyless break room (paper holiday decorations only serve to underline the dreariness). Employees wear bright red vests made from flimsy synthetic cloth (costumes by Arnulfo Maldonado) and the space is lit in harsh fluorescence (lighting by Oona Curley). What would compel someone to work at a place like this? Capitalism and desperation, of course.

(© Ahron R. Foster)

"I want to be part of a hardworking team that's focused on customer service," lies Emmie (an inscrutable Jules Latimer) during her job interview. An associate who has just been promoted to manager, Gar (a disarmingly unemotional Eddie K. Robinson) sees right through this, but he hires her anyway. Perhaps he notices the desperation on her face, which is marred by a giant wound where she allegedly fell after slipping on ice (the truth of this explanation is never fully established, just one of the many mysteries of this play that keeps our attention by not revealing everything).

Emmie (whose birth name is Emaani) meets her coworkers: Wendy (sweet as pie Ann McDonough), a former nurse who now works at Berry's as a kind of retirement purgatory; and Logan (a boyish Christopher Dylan White), an amateur rapper supporting his grandmother. They both spring into action to cover for Emmie when she accidentally bleeds on some merchandise, exhibiting an informal solidarity that no amount of union-busting can ever fully quash. And then there is Maxine (a fiery Danielle Skraastad), a rabble-rousing mother of four whose populist rhetoric against Berry's is a flimsy mask for selfishness. "I'd bodyslam a nun for a factory job," she admits. Judging by her pervasive rage, one suspects she is a big fan of her scrappy 54-year-old congressman, Bernie Sanders.

(© Ahron R. Foster)

In just six scenes, Booth depicts the trickle-down cruelty of American employment, in which poor people are promoted to management to keep their boots on the necks of even poorer people, absorbing all of the subsequent resentment (we see this clearly when the other employees sit around the break room tabulating Gar's paycheck — at the lavish rate of $9 an hour).

Director Knud Adams deftly stages this social dynamic while leaving room for the mystery inherent in Booth's script, which is not strictly social realism. Booth's penchant for magic takes its most jarring form in a strange character named Carlisle (played with Luciferian flair by Bruce McKenzie). The whole scene threatens to knock the play into another dimension, but it never quite does — a testament to Adams's steadiness.

We are given time to reflect during scene transitions, which Trey Anastasio underscores with his original vocal compositions. In these moments, the Phish front man convincingly channels Monteverdi.

(© Ahron R. Foster)

Latimer's quietly powerful performance, which relies on physicality far more than words, offers a steady center to the drama. While Emmie insists that she's a hometown girl, her coworkers all say that she doesn't look like she's from Paris (the not-so-subtle implication being that to look like you're from Paris, you have to be white). Regardless of her origins, Emmie is an alien to this world, just like most members of the off-Broadway audience; she becomes our Dante in this journey through retail hell.

By setting her play in 1995, Booth also pushes back on the notion that these kinds of exploitative labor practices are a recent invention. The roots of working-class discontent extend far deeper than the Internet age. In Paris, Booth removes a level of topsoil and allows us to see the rot for ourselves.