Notes From the Field

(© Joan Marcus)

Nationwide, one in 13 African-American adults cannot legally vote. This shocking statistic is projected on the upstage wall of Second Stage Theatre as a primer to the performance of Anna Deavere Smith's Notes From the Field, an expansive and engrossing look at how our education system led students (disproportionately from minority backgrounds) toward mass incarceration and the loss of the right to participate in our democracy. Despite some structural shagginess in the script, Smith keeps us riveted with her mystifyingly real performances. The result is a play that leaves us with the uncomfortable feeling that when it comes to race in America, progress is an illusion: While Black Americans of the Jim Crow era were denied the vote with poll taxes and literacy tests, today that disenfranchisement is more likely delivered through zero-tolerance policies and aggressive policing in public schools.

Few performers are more qualified to tell this story than Smith, who is among the most accomplished purveyors of documentary theater in the United States. Her solo shows Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 and Fires in the Mirror won her back-to-back Drama Desk Awards in the early '90s. Her last major show, Let Me Down Easy, examined the health care crisis in America. As in those previous works, Smith crafts Notes From the Field around a series of monologues (or "portraits") in which she completely inhabits the role of a real person, performing their words verbatim as she heard them in a series of research interviews.

For this play, Smith takes on 17 roles: There's Niya Kenny (a young woman who videotaped the arrest of a classmate), student concerns specialist (read: disciplinarian) Tony Eady, and Stockton super-parent Leticia de Santiago, to name a few. Smith whips the audience into a frenzy with her symphonic performance of pastor Jamal-Harrison Bryant's dramatic eulogy for Freddie Gray, leading some in the crowd to shout "amen" back at the stage. Although delivered in a much softer tone, her portrayal of longtime inmate Denise Dodson is even more moving for Dodson's admirable insistence on finding a way to positively contribute to society.

(© Joan Marcus)

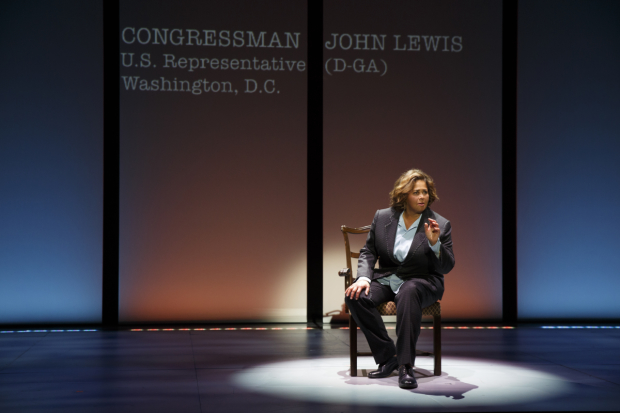

Director Leonard Foglia stages these monologues with rapid transitions and a minimal amount of scenery (sleek design by Riccardo Hernandez). Ann Hould-Ward costumes Smith is a few essential items for each section so that gives us an immediate idea of the character without too many frills (Smith remains barefoot through most of the show). Composer Marcus Shelby plays double bass and, like the Paul Shaffer to her David Letterman, remains onstage for some of the funnier portraits so Smith can riff off him. Employing a no-nonsense font, Elaine McCarthy projects names and basic bio information on the upstage wall for each of the subjects, occasionally flooring us with a statistic: 2.7 million American children presently have a parent in prison.

Smith masterfully weaves facts around personal narratives, giving the numbers a human face. We learn the underreported statistic that Native American men are four times more likely to be imprisoned than white men before we meet Yurok fisherman and former convict Taos Proctor. Principal Linda Cliatt-Wayman tells us about the embarrassment some of her 18- and 19-year-old students feel about only being able to read at a first-grade level before sharing that 85 percent of all inmates in U.S. prisons would have qualified for some sort of special education. After seeing Notes from the Field, it is hard to see this "school-to-prison pipeline" as anything other than by design.

"This country is always engaged in investments," says NAACP Legal Defense Fund director Sherrilynn Ifill. "One of the huge investments that we made was in the criminal justice system." Ifill is the first voice we encounter and she proves to be the ideal messenger of a big-picture perspective on how the individual stories of school failure and mass incarceration fit together; smartly, Smith brings her back in the second act, the perfect bookend to this show about the disastrous consequences of that "huge investment"…and then the play continues.

The last two portraits are of Bree Newsome, an activist who scaled a flagpole in front of the South Carolina statehouse to remove the Confederate battle flag, and Congressman John Lewis, a crucial figure in the civil rights movement of the 1960s. While both of these passages succeed at ending the play on a hopeful note (Smith is particularly moving in her spot-on portrayal of Lewis), they come as something of a digression from the gut-wrenching play we have just witnessed. Worse, Newsome's triumphant removal of the Confederate flag feels like a hollow victory in a country still so deeply mired in systemic racism, most of which is enforced without the use of symbols traditionally associated with racial hatred. It's only a feel-good ending if you haven't been paying attention for the previous two hours.

(© Joan Marcus)

Still, Smith undeniably convinces us that this is a discussion worth having. She seems acutely aware that a wide range of factors (historical oppression, militarized policing, new technology, multi-generation poverty) are contributing to the story she's trying to tell and not all of them can be fully explored in one show. Luckily, the program alerts us that Notes From the Field is only one part of a larger endeavor entitled "The Anna Deavere Smith Pipeline Project." We look forward to seeing the next installment.