In Conversation With Seven of Musical Theater's Leading Female Songwriters

The creative minds behind ”Fun Home”, ”Legally Blonde”, and more, talk about collaboration, pushing boundaries, and making their own opportunities.

(© Ashley Van Buren)

Lisa Kron and Jeanine Tesori, creators of Broadway's Fun Home, made history this year as the first all-female writing team to win the Tony Awards for Best Book and Score. The delay in this milestone has occurred not because of a lack of talent but because of the small number of women artists working in the industry, and the even smaller number of female-created works being produced on Broadway stages.

Female lyricists and composers are few and far between, and as such, they are faced with unique challenges as well as opportunities as they take on this largely male-populated industry. We gathered some of the most prominent women in the field at New York SongSpace to discuss the common experiences they share as women working in musical theater. Here's what Nell Benjamin (Legally Blonde), Amanda Green (Hands on a Hardbody), Lisa Kron (Fun Home), Lucy Simon (The Secret Garden, Doctor Zhivago), Georgia Stitt (Snow Child), and writing partners Zina Goldrich and Marcy Heisler (Ever After) had to say.

"It taught me to make your own work"

(© Ashley Van Buren)

Lisa Kron: I didn't start out as a writer. I was an actor. But I was told from the very beginning that there was no place for me in the theater.

Lucy Simon: Who told you that?

Lisa: My college theater professors who said, "You either need to lose fifty pounds or gain fifty pounds." As I like to say, I was told I was a character actress, which was a code word I realized later for "lesbian"…This professor said to me in a completely matter-of-fact way, "Well obviously, as you know, you don't convey any sexuality onstage." Why you would say that to a nineteen-year-old girl—

Zina Goldrich: Also a budding artist. You're just beginning to discover the things about you that make you unique and special and you're looking to grab onto those things. Whatever it was that they were responding to was something that clearly developed later into a quality that made you completely special for all the world to see.

Georgia Stitt: I hope you sent that professor a picture of your two Tony Awards.

Lisa: [laughs] When I came to New York, somebody said, "You gotta come downtown and see this company Split Britches"…and it completely changed my life. That was the moment I not only saw women who weren't supposed to have a place in the theater making theater, but I saw kinds of theater that I had never imagined before. They were making their own opportunities.

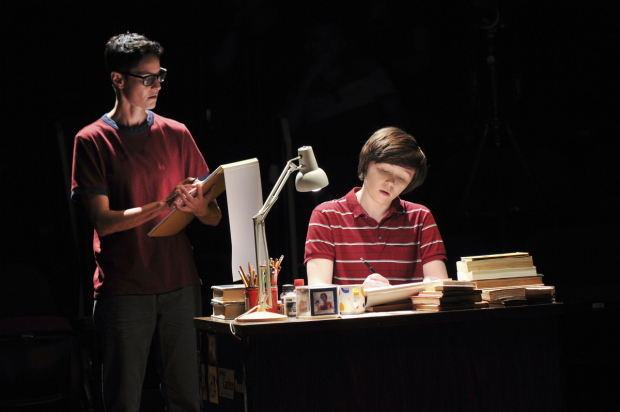

(© Joan Marcus)

Marcy Heisler: Like Lisa, I come at this from a performance background…When I came to Northwestern, I remember very clearly in their student variety show they usually cast two freshmen…And they kept moving me back and forth with this beautiful blonde wonderful friend of mine [for one of the slots]. And they did not cast me. I remember so clearly going back to my dorm room and crying and saying, "Why did this happen?" and it was in that moment when I said if I couldn't see the opportunity — if there really were only two slots in the world — then maybe the focus should be making more slots. Not only make more art, but make more spaces. So I wrote a song — this is embarrassing now — [but] I wrote a song for five character women called "Let's Kill the Ingénues," which was a good-natured way of poking fun at the character-women issue. It and I did indeed get into the show the following year, and it taught me to make your own work.

Amanda Green: There are a lot of character ladies in the room! I was an actor in college…I didn't start out wanting to write musicals [but] I wasn't getting work out of acting school, so I started singing in cabarets. Then I got into writing because of an ex-boyfriend. My heart was broken, and of course he and I wrote a song about how my heart was broken. But the power I felt standing in front of a microphone and singing the words that expressed the exquisite and unique heartbreak— it was intoxicating.

Zina: My father was a doctor and a jazz musician, so our house was a place where musicians came [and] they were all men. I loved the music that was being played and my folks never said to me that I couldn't do it. They would take me to Broadway shows and I would come home and I would play all the songs that I could remember. I didn't know anybody else who could do that. I didn't know any boys who could do that, frankly.

Marcy: Go, Zina!

Zina: I think that the main theme of my career so far is grabbing those opportunities when an inkling of something shows itself. Marcy and I have sort of treated our career that way. We wrote "Taylor the Latte Boy," which was a song that people actually knew and we wanted to publish a songbook. Pretty much everybody across the board said, "No, nobody's gonna buy this." And so Marcy and I decided, "How hard would it be to do it ourselves?"

Marcy: We were like Mary Kay Cosmetics.

Zina: We were selling our sheet music after our shows. We'd come in with these big bags of our music, and actors would come because they heard there were funny songs to be sung…The popularity of "Taylor" allowed us to put that in a book. That was what kind of started things. Marcy and I have a song that we do in our show called "Make Your Own Party," and clearly that has been a life philosophy for us.

"The balance of love and war"

(© Ashley Van Buren)

Lucy: I started as a performer and songwriter, and when I decided I [was] too old to get onstage, I thought I wanted to do musical theater because I loved the idea of writing for different characters. It didn't occur to me that there was a problem being a woman because being in the music business, it was different. It certainly was easier to be a man, but it wasn't that same kind of prejudice. Then Marsha Norman and Heidi Landesman got in touch with me about doing The Secret Garden. We were the first all-women production and that was quite amazing. I didn't feel any discrimination against me as a composer with The Secret Garden. I felt it enormously when trying to do Doctor Zhivago and getting all of the snobby [public] responses: "Well, she was good for The Secret Garden, but can she do something about a man?"

Zina: [laughing] They never ask that about men, do they?

Lucy: But it was a huge barrier…and it finally did get to me. And by the time I got to the final structure of who the collaborators were — there were two women [and three men] — the men had the power. I didn't have an ability to say, "No, this is not how I see this." I think in a collaboration, you have to be strongly supportive of each other, and when it breaks down, whether it's because of men or women or different characters, it really hurts the property.

Georgia: Lucy, can I ask, when you say you felt like they had the power…how did that manifest?

Lucy: Doctor Zhivago is really a balance between a love story and a war story. My passion for this property was in realizing the power of art and love to rise above the destruction of war to live on into the future…Handling the balance of love and war and politics is very tricky, and in this case, became a male/female, left brain/right brain thing. When we were in Australia, [director] Des [McAnuff] and I collaborated beautifully. When we came to New York, Des made it clear that he didn't want interference with his vision, and the balance shifted…It's the collaboration that has to work…And I think that maybe the difference in what my experience has been, is that the men are not willing to listen to the other side as much as women are.

"The thing that we must protect above all…"

(© Ashley Van Buren)

Nell Benjamin: I tell a story again and again [about Legally Blonde] where [my husband and cowriter] Larry [O'Keefe] and I had this idea for [Professor Callahan] to sing [Elle] a song [that] was saying, "Leave your classmates behind, be a driven career woman instead of trying to help Warner." And we got the note, "Elle Woods would not entertain this notion for a second!" And I said, "Why?" And they said, "Because she'd be putting her career above her friendships and her relationships!" I was like, "Sometimes, when women are alone in the dark and no one can see them, we entertain the concept of putting our careers before our relationships and friendships." It's a person thing — not a woman thing.

Marcy: I would rather look at things as relationship stories as opposed to female stories and male stories. Because what I think we're all trying to write are relationship stories.

(© Paul Kolnik)

Lisa: It's [not] necessarily a male/female issue. I think it's an issue of good collaborators/bad collaborators…If you're working with a director who has no respect for your work, in addition to having a different aesthetic vision for the piece, I don't know there's anything you can do. The [way] I often see women give up power is by taking care of the people in the room rather than their work. [That's a] very valuable skill that women bring into the room, but I think that we also have to learn that the thing that we must protect above all is our work.

Lucy: There has to be a give and take. Whether that's male, whether that's female…

Nell: I've never encountered anybody where I thought, "Wow, you are sexist, plain and simple." But I do think I agree, depending on who you pick [to collaborate with], you could have an easy time or you could have a really hard time. Part of the hard thing about breaking in is [most people] hire their own friends, and a lot of times those friends are male. I think it's an issue with minority-hiring too. You have to walk the friendly line and be like, "I'm friendly, you want to work with me," and not be, "I'm friendly, I'll do anything you say."

Georgia: Or, "I'm friendly, I'll be your assistant."

"How much do you push?"

(© Ashley Van Buren)

Amanda: I absolutely understand what Lucy was talking about. I feel I sometimes give away my power. Early on in my career, in rehearsal…I'd watch the guys just walk up to the stage and have these long conversations with the actors and I'd be back there [thinking], "How do I do it? Who do I talk to? Who's gonna listen to me?" It felt like there was this wall. It's gotten better, [but] I just don't think the door's open in the same way for a woman. I saw Betty Comden and my dad [Adolph Green] performing and writing and having these big careers [and] I did see Betty as a [role] model…I have no idea who wrote what with my father and Betty, but [it was] always, "She's the cool head at the typewriter and he's the one with the mad-cap inspiration." And I don't know if that's a fair characterization of their relationship.

Zina: I think it's a challenge to be as — I want to say "assertive" and not "aggressive," because there's really a fine distinction. But to be as "assertive" as we want to be — to be protective of our music, of our voice…You wonder, how much do you push?…I think maybe as women sometimes we want to make peace.

(© Friedman-Abeles)

Georgia: We were on a panel at the Dramatists Guild with Kristen Anderson-Lopez who was talking about how girls are socialized to be peacemakers — to be polite. Kristen said that when they were in tech rehearsals for Up Here at La Jolla Playhouse, there would be days where she and her husband, Bobby, who were cowriting the show, got notes, and her thought was, "We have to take some of these notes so that they don't think I'm a bitch."

Lisa: She also said she won't work on a project where there aren't two women in the room.

Georgia: She talked about Frozen being the first Disney-animated project where there were two women in the writers room. And let's look at what happened with Frozen.

Nell: Women say no differently in a weird way: "That is very interesting" or "I see your point." This is the way I think we're raised, to not blatantly say no to someone — particularly not [to] a man. You'll never get married!

Marcy: I think collaboratively you never want to say a solid no. You want to not only be heard, but to hear the other person.

Georgia: You can't always be the one fighting for everything. But you also can't be the person who's not ever fighting. When is your idea the one that's worth fighting for? Because you can't be "no no no no no."

Amanda: My first musical I started out with "no no no no no!" because I was freaked out…I had to learn to grow up. You have to learn how to give and take.

Nell: I did learn a really cool trick from another female collaborator. She [and her male collaborator] had reached one of those little impasses that you reach when you both have an idea. And she said, "I'm sorry, why the resistance to this idea?" [I thought], "Who gets to ask that?" I had never been in a meeting where a woman had asked a man, "I'm sorry, what is the problem with this idea?" It was so super effective. It would never occur to me to actually say, "Look, I'm sorry, what is your problem with my idea? Can't we just try it?"

"Because I'm female"

(© Ashley Van Buren)

Nell: There is a certain amount of opportunity now with females driving ticket prices and ticket-buying. It seems like every now and then you hear, "We need a woman on this project!"

Georgia: I'm working right now on a show for Arena Stage…Molly Smith is the artistic director and she brought a book to me and said, "Will you work on a team to adapt this?" And what I learned after I said yes was that they had had a team that was all male and it's a female author of the novel and a female protagonist and she said, "I cannot create a team for this property that does not have a woman on it." That's why I got the job… and in that case I'm very clear that I got the job because I'm female. It may not have come to me otherwise. She had my back in that case — or she had womankind's back…I'm not sure I can think of a man who's done that for me. There have been many men who have given me opportunities and given me jobs, but [she] saw something and said, "I see an opportunity to help you [move] forward."

Lisa: Women don't have an expectation that their work is going to be chosen or produced. So I think an important thing to say is not just that women have taken it upon themselves to become these things, but that they've been given jobs in the theater. That's what gives us the idea that we can have a career in the theater.

Nell: I think it's a good thing to keep in mind at all times. I've been through director searches and in the room at one point I said, "There are no female directors on this list." And they said, "Well, we're looking at a certain level." But I know there are female directors at that level. And they said, "Don't we just want the best, regardless of gender?" And I said, "No. Yes, ultimately we want the best person. But it's a fallacy to say that they wouldn't be the best because they're female." Put them on the list and meet them. I don't think the people who don't put them on the list are sexist pigs. They think of their friends or, "I just saw this show on Broadway so we put that person down." It just takes a little extra effort.

Marcy: The industry as a whole has to stop pegging everybody and start listening more. We all develop relationships, and you really want to work with the same people again and again. But some of it is just developing your own voice…I think that the best theater is built in whatever it is that you're thinking and feeling — something that no one but you could have written.

(© Ashley Van Buren)