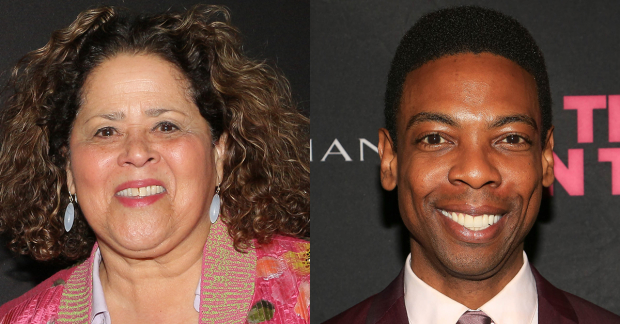

Anna Deavere Smith Reignites Her Fires in the Mirror With Michael Benjamin Washington

Washington picks up the flame of this landmark solo play to kick off Smith’s Signature Theatre residency.

The 1992 drama Fires in the Mirror not only introduced the theater world to playwright and performer Anna Deavere Smith, but also to a style of playwriting called "verbatim theater." Exploring the deaths of the young African-American child and the Orthodox scholar that led to the Crown Heights race riots in 1991, the work comprises monologues taken directly from interviews that Smith conducted with members of the black and Hasidic Jewish communities connected to the event.

In the original production at the Public Theater, Smith played all 26 characters, ranging from the Reverend Al Sharpton to Lubavitcher Rabbi Shea Hecht. For the first-ever revival of Fires in the Mirror, directed by Saheem Ali as part of Smith's Signature Theatre residency, she has decided to pass the torch of the play on to a different actor, recent The Boys in the Band star Michael Benjamin Washington.

Giving her plays to new actors is a way of gifting them a challenge to use their entire arsenal of talent. While Washington was still figuring it all out at the time of our conversation, Smith wasn't worried in the slightest.

(© Tristan Fuge/Tricia Baron)

Anna, when Signature came to you with this residency, what was the impetus for reviving Fires in the Mirror with a performer other than yourself?

Anna Deavere Smith: I've always wanted to turn it over to other actors, because, in addition to telling a story, I was trying to propose another idea of acting, skill-wise. I campaigned for a man to do Fires in the Mirror, because I thought it would be interesting to see what happens when a male sensibility, particularly a black male sensibility, brings not just his imagination, but his understanding of race in America, which is different than mine. Our experiences of race in America are gendered. Everybody has had a different experience.

When Michael came to audition, I was in Germany, so they Skyped me in, which is never the best situation. The thing that came across was his level of preparation. He came in with a lot of energy. He was very meticulous and excited, and crisp in every way. That went across the airwaves, so to speak. I think we've lucked out with Michael.

Michael, what was your first exposure to Fires in the Mirror? Why did you want to take on this challenge?

Michael Benjamin Washington: When I was in middle school and high school, I did competitive speech and debate, and everybody who was on the circuit would have to read whatever the participants were performing. A young girl did Fires in the Mirror, so we read it in high school. When I got to NYU, we read and discussed it at great length, and it was all a very intellectual understanding of the psychology of these people. But as an actor, you have to delve into the emotional life, which is what we're doing now.

This is not an easy one by any means, especially coming from The Boys in the Band, which was an ensemble drama where I didn't speak that much and got to practice the art of listening. Now, I don't stop talking, but still have to keep the elements of listening. Each monologue is a conversation with someone, and you have to see the other person there and respond. My parents are so happy when I say this, but this is where my degree kicks in. NYU Tisch School of the Arts taught me how to do this kind of work.

Anna: It's very demanding, and I have to say, to see Michael do it helps me appreciate what I did. I didn't expect the original run. I thought it was gonna be three weeks, and it kept getting extended at the Public Theater. I had only done this type of work as a one-shot deal: make a play; show up; do it one time. So to do it as a run is a workout. It's an enormous amount of material you're carrying around in your head, intellectually, emotionally, and vocally.

When I was developing this way of working, it was because I wanted to develop my own skills. It's an opportunity to refine your psycho-linguistic skills and avail yourself of the emotional lives we have. You're not going to find many opportunities to use those skills to this extent.

Michael: Have not yet.

Anna: But you've trained the whole time. You're ready.

Michael: I'm very happy to be used in this way.

(© Joan Marcus)

So many revivals now rework the original material with the benefit of hindsight. Was there any interest in doing something like that for this production?

Anna: That's a whole other exercise I didn't want to get into, and it would have driven Michael crazy. I dropped one character and I made one change, and I thought that's all I should do. I thought we should take what's written and see if it can resonate right now. I hope it does.

Michael:' It doesn't feel like I'm doing a period piece, even though it's about a specific event in history in a very specific place. The headlines I'm reading about anti-Semitism in Germany and the conflicts with the police in the African-American community translate so easily to this play. There's nothing that seems dated about it.

Michael, have you asked Anna for any performance advice?

Michael: Anna saw a run-through of the first act and I asked her which character she thought was the most and least successful. She hated that question.

Anna: I was appalled.

Michael: Anna is not a result-oriented person at all. She's a process-oriented person. In the second act, there's one woman, Roslyn, who I'm still trying to figure out. I think I'm empathetic to her, maybe to a fault, so I don't see, at that point in the show, the conflict in her. It's a great challenge for me to figure out how to propel her past the footlights. Anna, who was hard for you to pull off in this?

Anna: Rivkah was very hard.

Michael: That was the one I was scared of.

Anna: It's difficult to say why. Some people are harder to pull off, but I'm committed because I've made the choice to put them into the play. That's why this type of work is enormously satisfying. It introduces you to the beauty and complexity of people.

Can you explain the way into Roslyn?

Anna: I wouldn't do that. I wouldn't speak publicly in that way about a real person. That's between me and my creator.

Michael: Thanks for trying. I appreciate it, bro.