A Playwright's Political Madhouse

Our theater’s vitamin deficiency: not enough George Bernard Shaw.

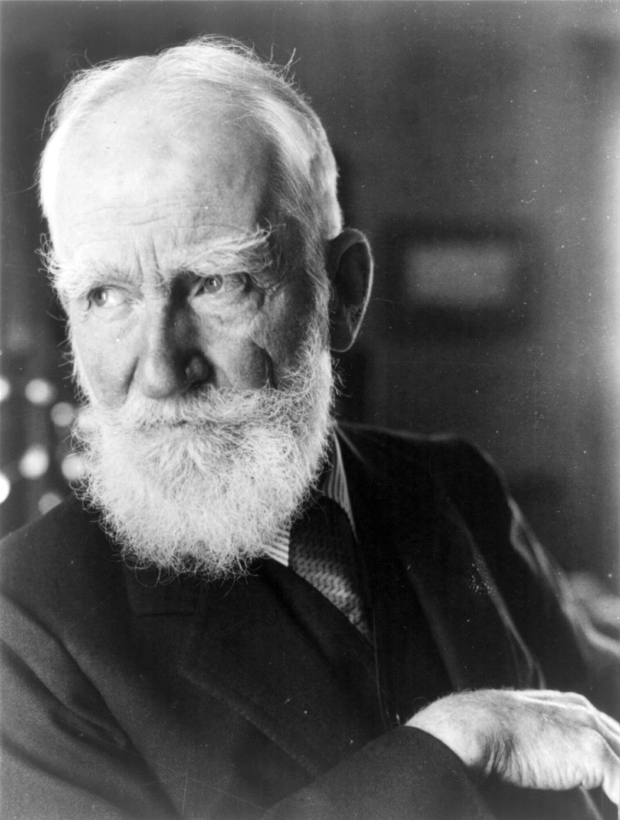

While we've been going through the most frazzling and divisive election in our history, I've found myself thinking, again and again, about the playwright whose works I love most and don't see nearly often enough: George Bernard Shaw. As of November 2, he will have been dead 66 years, and productions of his work, which used to be fairly frequent in New York, have dwindled to a paucity.

David Staller's Project Shaw, now a decade old, continues its trek through GBS's collected works in monthly one-night readings. In full productions, off-Broadway's Irish Rep and the Pearl Theater Company have kept Shaw on their rosters, most often recently in collaboration with Staller's Gingold Theatrical Group. On Broadway, the Roundabout has intermittently done its bit for Shaw's more familiar titles, most recently with Mrs. Warren's Profession — unfortunately a misfire — in 2010.

That doesn't add up to much. These days, I suspect that most New York theatergoers and theatermakers know Shaw, if at all, only as provider of the source material for My Fair Lady. To those of us who love him passionately, it hurts to imagine the man widely viewed as the second-greatest English-language playwright reduced to a musical-theater footnote — a bearded Irish equivalent of the Trapp Family Singers or Gypsy Rose Lee's childhood.

Some of the reasons for our theater's relative neglect of Shaw are understandable. Apart from the now-customary obeisances to Shakespeare and Chekhov, our producing institutions don't seem to care much about any writer from the past. Even esteemed recent playwrights like Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller meet new audiences only through their two or three most familiar titles. And like other playwrights from bygone days, Shaw makes economic demands — large casts, multiple settings — hard to fulfill on today's skyrocketing budgets.

Then, too, Shaw's plays are famous for relying heavily on verbal expression. The complaint of wordiness began early in his career, becoming something of a joke to him: Both Man and Superman (1903) and Misalliance (1910) end with jokes about their characters talking too much. Shaw's most outrageous version of the joke closes the first act of his late play Too True to Be Good (1932), in which a character declares, "The play is now virtually over, but the characters will discuss it at length for two acts more. The exit doors are all in order. Goodnight."

Like many of Shaw's comic paradoxes, that line is both a fib and a truth: Though a great deal happens in Too True's next two acts, the events don't really advance the story; the three main characters remain much as they were at the start, and they do discuss their situation at length, albeit in unexpected and often startling terms. "Throw off the last rag of your bathing costume, and I shall not blench nor expect you to blush. Swear; use dirty words; drink cocktails; kiss and caress and cuddle until girls who are like roses at eighteen are like battered demireps at twenty-two […]. But how are we to bear the dreadful new nakedness: the nakedness of the souls who until now have always disguised themselves from one another in beautiful idealisms […]" This fervent speech, the play's last, ends on an unfinished sentence. The hero, vowing that he will continue preaching even though he has nothing to say, keeps talking till he is entirely covered by fog. The old joke about talking too much has merged with a new and unnerving despair.

Such troubling images and ideas may be among the reasons many theaters resist Shaw these days; they are also part of the excitement that makes people love him. Shaw remains in his writing, as he was in life, a source of irritation, even of anger, to many. He set his course as a troublemaker early on, and he hewed to it enthusiastically. That he could become, while doing so, both a beloved popular entertainer and a literary artist esteemed worldwide, suggests the power of his extraordinary gifts.

His astonishingly capacious mind produced a staggering range of achievements. Those who don't rate his 50-odd plays as a body of work ranking second, in English, only to Shakespeare's, must still contend with his status as, incomparably, the best theater critic who ever wrote, and one of the world's dozen or so best music critics. Then they have to take into account the half-dozen novels; the essays (sometimes book-length) on everything from churchgoing to criminology; the economic treatises; the political pamphlets; and the innumerable volumes of his collected correspondence. Nearly all of these works remain vividly alive, written in a brilliant rhetorical prose that supplies instant delight when read aloud. Even when the ideas expressed now seem outrageous, outdated, or hopelessly wrongheaded, Shaw's style still captivates.

(© Jenny Anderson)

His relevance can suddenly leap out at you, as in this instance, from his gigantic, rarely produced five-part epic, Back to Methuselah (1921). In Part 2, set just after World War I, a philosopher tells a leading Tory politician, "Flinders Petrie [a prominent archaeologist] has counted nine attempts at civilization made by people exactly like us; and every single one of them failed just as ours is failing. They failed because the citizens and statesmen died of old age or over-eating before they had grown out of schoolboy games and savage sports and cigars and champagne. The signs of the end are always the same: Democracy, Socialism, and Votes for Women […]." The politician replies, "I am glad you agree with me that Socialism and Votes for Women are signs of decay." "Not at all," the philosopher demurs, "they are only the difficulties that overtax your capacity. If you cannot organize Socialism you cannot organize civilized life; and you will relapse into barbarism accordingly."

As this quote suggests, Shaw's prescience brought him little contentment as the 20th century wore on. Born in 1856, he lived till 1950, creating nonstop. Inevitably, contemplating the span of his work reveals flaws, some of them deep and painful, as well as splendors. Next week I'll try to balance the account.

To read Part II, click here.

Michael Feingold has twice won the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism, most recently in 2015 for his Thinking About Theater columns on TheaterMania, and has twice been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Criticism. He serves as chairman of the Obie Awards and has also worked as a playwright, translator, and dramaturg.