Is Brandy's Cinderella Really as Wonderful as It Seems? Disney Plus Tests Its Timelessness

The multicultural musical event was groundbreaking in 1997. Does it stand up in 2021?

(image provided by Disney Plus)

"The Glass Slipper Fits With a 90's Conscience," reads the New York Times review of Disney's 1997 TV musical Cinderella, which famously boasted a multicultural ensemble led by pop stars Brandy and Whitney Houston. Today, we have to raise an eyebrow at the term "90's Conscience" considering the spate of overdue apologies society has had to proffer to public figures (mostly women) who ushered out the 20th century – Monica Lewinsky, Britney Spears, and Anita Hill topping that list. And yet, as millennials celebrate the arrival of Brandy's Cinderella on Disney Plus, the project seems to have maintained its aura as the thing we got right in the 90s.

Still, nostalgic reverie is a powerful drug, so we have to wonder whether that assessment can truly withstand the scrutiny of a re-watch nearly a quarter of a century later. As calls for anti-racism within the theater community build, and grassroots organizations like Broadway for Racial Justice gain support, it's time to ask ourselves: Is Brandy's Cinderella the sweet invention of a millennial's dream, or is it really as beautiful as it seems?

I was only 7 years old when Cinderella first aired on ABC, but as a fresh convert to the church of musical theater, I distinctly remember it prompting my first exposure to the term "color-blind casting," and feeling that the concept was intrepid and paradigm-shifting (I cannot confirm those were the exact words I used at the time). How the novelty of it was apparent to me with only a few viewings of VHS 1 of The Sound of Music in my Rodgers and Hammerstein repertoire (I didn't like the Nazis on VHS 2) speaks volumes about the state of cultural and racial representation up until that point.

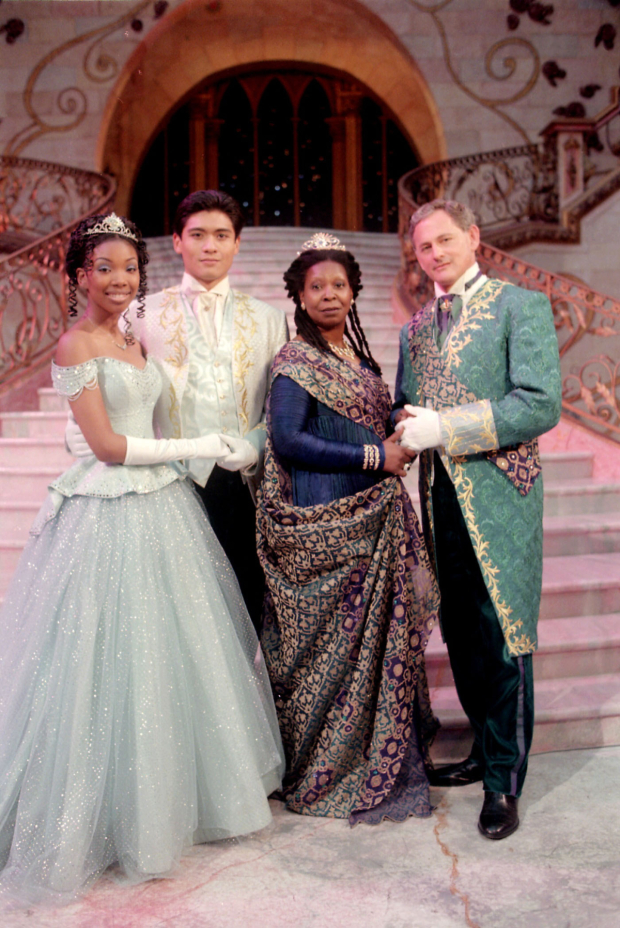

Our grandmothers had Julie Andrews. Our mothers had Lesley Ann Warren. We had Brandy. Regardless of how skillful or not history judges the 18-year-old singer's doe-eyed performance, she gave us a new kind of fairy tale – one where the princess does not have skin as white as snow, nor does she desire to be treated like a princess, but rather, "like a person with kindness and respect." Pair that with an idyllic melting pot of a kingdom where white king Victor Garber and Black queen Whoopi Goldberg produce the dreamy Filipino prince Paolo Montalban, and all signs point to the Platonic ideal of a postracial society.

(image provided by Disney Plus)

But of course, we were not – and are still not – living in a postracial society. The difference between 1997 and 2021 is that more of the professionals who make up the arts industry today realize that postracial entertainment is not, and should never have been, the goal. Two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright August Wilson was ahead of his time in his own stance on this issue. In 1996, a little over a year before the release of Cinderella, Wilson delivered an address on Black culture at Princeton University, bluntly stating, "Color-blind casting is an aberrant idea that has never had any validity other than as a tool of Cultural Imperialists who view American culture, rooted in the icons of European culture, as beyond reproach in its perfection…We do not need color-blind casting; we need some theaters to develop our playwrights."

Wilson's sentiments may be too cut-and-dry for some, but his opinions do circle the increasingly prevalent and nuanced conversation about "color-blind" versus "color-conscious" casting. In his speech, Wilson used the specific example of an all-Black production of Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman, describing it as a "play conceived for white actors as an investigation of the human condition through the specifics of white culture." While a color-conscious production may have the ability to add a new cultural lens to an existing property, a color-blind production considers race as inconsequential as fairy dust – which happens to work for a story like Cinderella that literally turns on the use of fairy dust and can hardly be described as an "investigation of the human condition."

Last June – in the early days of the Broadway shutdown and closely following George Floyd's murder – musical theater writer and performer Heath Saunders (Great Comet) wrote at length about the complexities surrounding the visibility of Black bodies in productions (color-blind, color-conscious, or otherwise) penned largely by white artists (Cinderella's score is of course written primarily by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, and the teleplay was penned by A Gentleman's Guide to Love and Murder scribe Robert L. Freedman). "The simpler use of a Black body onstage," says Saunders, "is in an 'imagined' world. This is to say, a musical in which the Black bodies play characters who, as written, do not see the Blackness of themselves or of other characters in the show."

That description encapsulates the safe niche Cinderella was able to nestle into in 1997, giving all of us at home a fanciful world of make believe where race is categorically irrelevant. And yet, watching it over two decades later, there are moments where we can see just how "color-blindness," even in the realm of fairy tale, eliminates opportunities for storytelling. In the film's climactic scene, Cinderella asks her evil Stepmother (played by the distressingly ageless Bernadette Peters) why it would be so hard to imagine the prince falling in love with her. "Because – you're common, Cinderella," she answers. "Your mother was common and so are you. You can wash your face and put on a clean dress, but underneath you'll still be common."

Was it truly preferable that young girls of color across America not feel the specific resonance in that moment? The production itself gave us clear instructions to turn a blind eye to any implicit racial commentary. Because we collectively ignored those instructions, Cinderella remains the thing we got right in the '90s.

(image provided by Disney Plus)