How Journalist David Holthouse Put His Harrowing Story Onstage

With the help of director Markus Potter, Holthouse brings the story of his childhood rape and the planned murder of his attacker to the stage.

It's been ten years since David Holthouse first wrote a personal essay for the Denver Westword detailing his experience being brutally raped by the teenage son of his parents' friends at the age of seven and his months as an adult meticulously planning to murder his rapist. Since then, a version of the arresting story has been aired several times on NPR's This American Life where it caught the attention of several Hollywood bigwigs and one stage director — Marcus Potter.

While Holthouse said no to Hollywood, he did say yes to Potter , with whom he eventually formed a collaborative relationship, adapting Holthouse's essay "Stalking the Bogeyman" for the stage. The resulting play premiered at the North Carolina stage company in 2013 and is now playing in an open run at Manhattan's New World Stages. Holthouse, a journalist, spoke with TheaterMania from his home in Alaska about the decisions that brought Stalking the Bogeyman to life onstage.

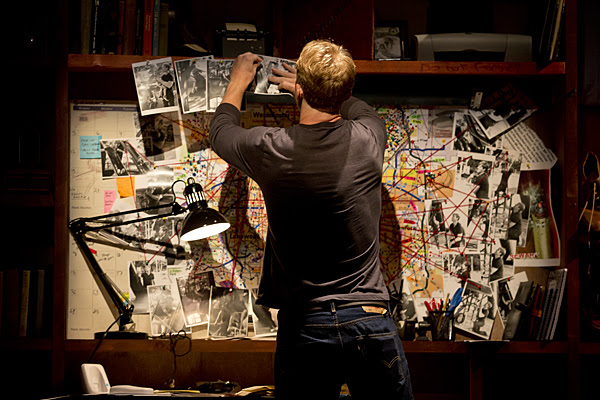

(© Jeremy Daniel)

What was the process of deciding to put your story onstage?

I first wrote the story as a first-person essay [that] was published in the Denver Westword, and that was published about ten years ago in mid 2004. And then Ira Glass contacted me in 2010 about turning it into a This American Life episode.

After the episode aired, I was contacted by several directors and screenwriters from Hollywood about turning it into a movie. And none of their takes ever felt right to me. They were saying things like, "Well, David's gonna need a love interest in this story, of course," or, "We need to make this more of an action-movie kind of thriller. I mean, we'll still keep the core of it there but it needs to be more kind of an action movie." And I just didn't go for any of those. And then Markus Potter called. He basically sent kind of a message in a bottle to me through American Public Media that said, "Hey, could you put me in touch with the guy who did that episode?" And because Markus was coming from the theater world, I immediately gave him a little more credibility on how he might represent the story. So I called him up and what he had in mind for an adaptation was to hew very close to the truth and to use as much of the language from the original story as he could work into the play. So the more I talked with him the more confident I became that adapting it as a piece of live theater rather than a Hollywood action movie was the way to go.

(© David Gordon)

What were you most concerned with when putting this story onstage?

Markus and I came to an agreement that I would be able to read and sign off on every version of the script. And he honored that and was very receptive to taking notes and letting me rewrite some scenes — especially very late in the game. I got New York in early September and I started sitting in on rehearsals. Once I saw the play being rehearsed, I thought there were some scenes that weren't working, and Markus and I rewrote them together. I bring that up only to say that throughout the process, up to the very end, he very much treated me as a collaborator in creating the adaptation. He didn't just take my story and run with it off in some wild direction he wanted to go.

It's such a difficult story. What do you hope audiences will take away?

Well, obviously I hope that parents will take away to watch out for people around their kids. And I hope that other survivors of any kind of childhood trauma will take away that there is a healing power in reckoning with your secrets. And it's interesting…at the end of the play, when the last line is delivered it's like the audience doesn't know what to do. It's just kind of like stunned silence for a few seconds. What I've found in talking with people who've just seen it is that it was equal proportions people who wanted to buy me a stiff drink and give me a hug. And some of them wanted to do both, which is my favorite response.

What do you think is gained when the story doesn't come directly from you?

I think that one of the positives of having someone other than me up on stage telling the story is that it removes it from just being a story that's just contained within my life. When I was growing up, when I was a kid and I had been sexually assaulted when I was seven, I thought that it was like a freak occurrence and I thought it made me a freak. I thought it was just like this very sort of rare and horrible thing that had happened to me. And in fact, that's far from the truth. Sexual assault of children in the United States is an epidemic…Basically, it's like the David who's up there on the stage is like a stand-in for millions of people at that point.