How Director Thomas Schlamme Turned The West Wing Into a Play — for One Episode

Find out what it took to bring ”Hartsfield’s Landing” to the stage for an HBO Max special event.

Very few of the filmed theater pieces that have proliferated over the past eight months have actually felt like the real thing. One was Hamilton. Another was HBO Max's A West Wing Special to Benefit When We All Vote.

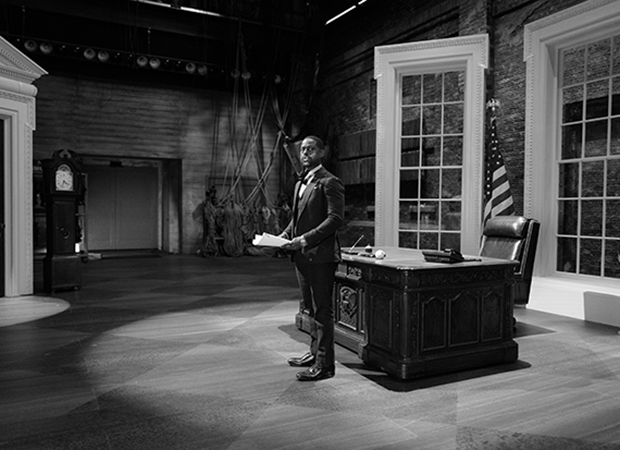

The hourlong event, now streaming, is a re-creation of an episode from 2002, written by creator Aaron Sorkin and titled Hartsfield's Landing. It centers on literal games of chess between President Josiah Bartlett (Martin Sheen) and staffers Sam Seaborn (Rob Lowe) and Toby Ziegler (Richard Schiff), and a figurative one with China, all as Deputy Chief of Staff Josh Lyman (Bradley Whitford) tries to account for 42 votes in a presidential primary in a small New Hampshire town. There's also a prank war taking place between Press Secretary C.J. Cregg (Allison Janney) and presidential aide Charlie Young (Dulé Hill).

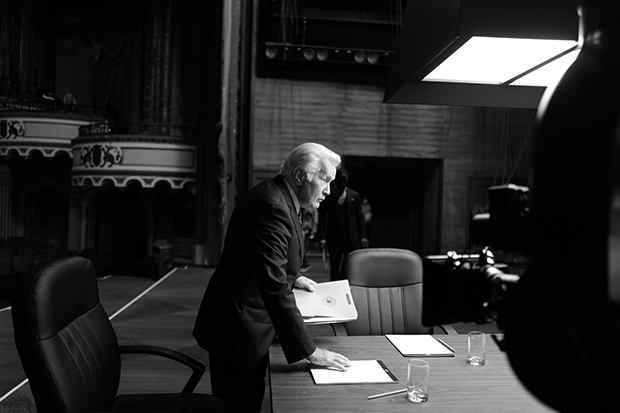

Executive producer Thomas Schlamme didn't take the reins of the episode 18 years ago — that duty fell to Vincent Misiano — but he picked them up here in a most unexpected way. Schlamme didn't simply re-create the episode, he turned Hartsfield's Landing into a theater piece. Filmed at the Orpheum in Los Angeles, Schlamme, production designer Jon Hutman, and cinematographer John Lindley's used the minimalism of a stage show — a desk here, a door frame there, and a couple cones of light — to conjure the familiar world of the Oval Office without the trappings of a big Hollywood production. Here, Schlamme tells us how it was done.

(© iDominick/Wikimedia Commons)

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Did you come into this project with the intention of turning it into a play?

The original concept was to do a virtual reading for the Actors Fund, and I told Aaron he didn't need me for that. When HBO Max and Warner Brothers got involved, he asked for my help. He had already talked to the actors to see if they were interested, and in his head, I think it was nine stools on a stage and everyone holding scripts.

I then began to read the script over and over, which has always been the process for me. I took a class with Harold Clurman before he died where he said, "If you do a play, you should read the play 100 times." I'm dyslexic, and if I actually read a script 100 times, it would take years. What he meant is that you can't read it enough.

I call every script I get a "play," even though it's a television show. It has a beginning, a middle, and an end, and it usually falls into a three-act structure. After I read Hartsfield's Landing a few times, I realized that it could actually be done as a live show: it takes place over one night and except for one or two scenes, it's contained in the White House. What I'm always trying to do with Aaron's work is open up what he has written, which is actually a play, and turn it into a TV show. But that was almost the opposite of what this particular project was. My interest was to create the emotion of a theatrical piece and shoot it as if my set was the Orpheum Theatre in Los Angeles.

(© Eddie Chen/HBO Max)

Walk me through building the episode for the stage and the adjustments it took.

Once I looked at the script and built a floor plan, it was easy to open up. It wasn't my genius. This scene followed that scene, I could connect set pieces, and then pull back with the cameras and see that we were on a stage. It wouldn't be easy to adapt so many West Wing episodes the way this one was, and I think Aaron was a little apprehensive when I kept saying "I'm going to do it as a play." He kept saying that he wanted the actors holding their books, and in my own manipulative way, I kept telling the actors that they had to be off book. Why do an Aaron Sorkin script unless you're going to get people emotionally involved? It wouldn't quite work if they were holding books. I wanted the intimacy of people really relating to each other.

The show was choreographed and completely designed and lit before the actors even got onstage. There was no real rehearsal — I did separate Zoom rehearsals of individual scenes with Richard Schiff and Martin Sheen, and Rob Lowe and Martin Sheen, but I didn't want to work on it too much. I wanted it to feel as alive as possible when we got there. I had the enormous advantage of having four years of trust and 15 years of remaining friends with all of these people, but truly, until everyone saw it, they didn't really get it.

(© Eddie Chen/HBO Max)

Most of the West Wing cast members are theater people. Did they step onto the stage and start projecting to the balcony, only for you to rein it in?

I don't think so. This was never done with a live audience, so I didn't have to do that thing of pulling everybody down. As Janel Maloney said, "It was like I had a fever dream and it was 20 years ago, and we're all on an empty stage doing an episode, and Tommy is wearing a miner's mask." I think they fell back into it, since there were cameras, and the blocking was motivated by the language of the scene, and we were performing the way that we've always performed.

(© Eddie Chen/HBO Max)

Why shoot in a theater as opposed to a soundstage?

I'm a fan of movies that use theaters, whether it's The Last Metro or Birdman or Bullets Over Broadway. You have this incredible location and it has so many curves and light and emptiness. It can be a subliminal character in the way that it's framed and shot.

Aaron was worried that it would feel weird on a stage if we didn't hear laughter. The show would have been 15 minutes longer if we had a real audience, just from the applause alone when Martin Sheen comes down the stairs. But I wasn't shooting it as if we were watching a play in a proscenium. I was behind them. I exposed the wings. The way in at the very beginning was showing the shadow of W.G. Snuffy Walden while he was playing the theme song, and coming around him and seeing the empty theater. Stripping it down from the whole orchestra to just a guitar was a metaphor for what people were in for, and they got that. That was the key visual: It's not my father's West Wing, but it's still The West Wing.

My production designer, Jon Hutman, was a very rich partner in all of this. He started with a lot more, and I told him we had to pull it back. We lit it with theatrical lighting, not because of theater, but because the show has moments of light and dark, and we should be walking in and out of that. We assumed that 99.9 percent of the people watching would have seen The West Wing. It wasn't going to be like "I wonder what that show is." So we had the enormous benefit of having four pools of light and those big white door frames and reducing everything else, and everyone got what that was, because they have such a strong memory.

It was a treat, because it served my approach to work at this point in my life. I just don't need that much syrup anymore. I put a lot onto that show when we were originally designing it. If you opened any drawer on that set, it was filled with stuff that would be in the drawers of people who worked in the west wing of the Oval Office. The file folders were never blank, they were filled with bills or information about bills, to give it as much reality as possible. I'm so appreciative that people got the minimalism here and that it wasn't just actors on stools.

(© Eddie Chen/HBO Max)