Review: Broadway Set Designer Beowulf Boritt on the Magic of Transforming Space Over Time

The Tony Award-winning designer reveals the dynamic process of scenic design at the highest levels of the theater industry.

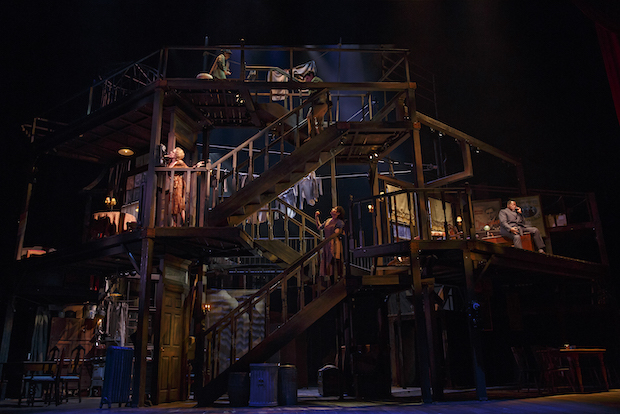

(© Joan Marcus)

One of my vivid memories of the past theater season is seeing set designer Beowulf Boritt standing placidly at the back of the Shubert Theatre during a Monday evening performance. Improbably, he had designed a rotating set for POTUS, knowing that even a slight delay in the turntable had the potential to sap the momentum from this door-slamming White House farce. And yet he betrayed no sense of dread, maintaining a poker face beneath his signature cluster of curls, the stage lights reflected in his thick-rimmed glasses. As the play whirled toward its hilarious conclusion, his apparent confidence (and the unconventional design) seemed entirely merited. He took a risk and it paid off.

That one line might very well summarize the 51-year-old designer's remarkable career, during which he has made a tiny version of the Seine River flow through Studio 54 and employed real trees on the set of Come From Away. Boritt doesn't discuss those productions or POTUS in his new book, Transforming Space Over Time: Set Design a Visual Storytelling with Broadway's Legendary Directors. However, he does give readers an intimate look into his process when working with some of Broadway's biggest directors: James Lapine, Harold Prince, Kenny Leon, Jerry Zaks, and Susan Stroman, for whom Boritt has designed several sets including POTUS and The Scottsboro Boys (that's musical's heartbreakingly curtailed Broadway journey receives its own chapter). The book is not only a record of some of Boritt's most innovative work, but an invaluable guide to collaboration at the highest levels of the industry.

(© Tricia Baron)

Boritt gives detailed overviews of six productions (Act One, The Scottsboro Boys, Much Ado About Nothing, Prince of Broadway, Meteor Shower, and Sondheim on Sondheim), revealing the multi-year process of visualizing a set, trying to find a way to build it within the allotted budget, and then introducing that set to actors and live audiences — which often leads to unforeseen complications and last-minute changes. The set designer must be at once an artist and engineer, dreaming up strange worlds that present practical problems, and then solving those problems. And even the ability to do that doesn't necessarily mean the design will be any good: "There is a constant danger," he warns, "when you work hard that you begin to believe it's good simply because you're happy to have conquered the challenge." Brutal self-criticism becomes a primary tool of the trade.

The inclusion of early sketches and successive drafts (many of which are included in this delightfully visual book) show just how much work goes into a set before it is even built. Boritt's accounts of the perils of the creative process make for a surprise page-turner as he does battle with cheap producers, juggles the demands of multiple projects, and is regularly rescued from certain doom by his stalwart associate Alexis Distler, the Robin to his Batman.

Boritt chases each production chapter with an extended chat with that show's director. This allows them to discuss not only Boritt's designs, but those of the visionary scenic designers that came before him. Boritt's admiration for Boris Aronson is particularly apparent as he speaks with Harold Prince about working with the original designer of Cabaret, Fiddler on the Roof, and Company.

(© Beowulf Boritt)

The final two chapters are a conversation between Boritt and Stephen Sondheim (a lovely memento of how the late composer thought about design) and a brief bit of advice for young designers. Boritt doesn't believe that there is a formula for succeeding in the theater: a healthy approach to rejection, an ability to pull all-nighters, a particularly memorable name — it all helps. And even after you've created what you consider to be some of your best work, it doesn't mean that everyone will share your assessment: "Everything was magical," he says about the opening night of The Scottsboro Boys. "Then the New York Times review came out."

Unfailingly cordial in front of the press, Boritt the author reveals a new side of himself. Whether it is throwing a "calculated temper tantrum" during tech for Meteor Show (he was worried that a malfunctioning set move wasn't being taken seriously) or screaming at a dissatisfied Harold Prince that the set for the Phantom section of Prince of Broadway conformed exactly to the rendering Prince approved, Boritt confesses to expressing real human emotions in a job that often seems to come with two conflicting directives: Pour your heart and soul into a design and then turn to stone during its execution. Prince, it should be noted, had his own vivid memory of Boritt during tech for Paradise Found at the Menier Chocolate Factory: At one particularly difficult point, the set designer stood onstage and shouted, "Fuck this fucking, fucked, fuckhead theater."

(© Dan Kutner)

It has become fashionable recently to question everything about how theater was made in the past century — to tear down the statues of the prickly "great men" who made it and to attempt to make the stage a healthier workplace for the next generation. This is an admirable goal, but I often wonder what will be lost should this reformation go too far. Can the theater-making process, which habitually touches messy emotions and dangerous ideas, ever conform to the conflict-averse standards of a corporate HR department? I have serious doubts about the quality of work that can come from a theater run like an accounting firm.

Boritt offers some advice when it comes to getting steady work in the theater: "Don't be an asshole," which seems like a good tip in any field, especially one that has 100 applicants for every available position. One need not become an automaton, however, in the quest not to be an asshole. Transforming Space Over Time is not just a memoir of one of the theater's most reliable designers, but an account of the emotional balancing act he had to perform to get to that position.