Point-Counterpoint: Is Rent a Bad Musical?

Our critics debate Jonathan Larson’s loved and loathed Broadway show.

Jonathan Larson's Rent is one of the most popular Broadway musicals of all time: It ran for over 12 years at the Nederlander Theatre, the original cast recording has sold over 1.3 million copies, and countless professional and amateur productions have been mounted around the world. But is it any good?

Television audiences will have a chance to reevaluate Rent (or experience it for the first time) on January 27 when it airs on Fox. While these live television productions have typically been reserved for inoffensive fare like The Sound of Music and The Wiz, Rent tackles the gritty bohemian underclass of New York City in the late '80s: Against the backdrop of the AIDS crisis, roommates Roger and Mark resolve not to pay any rent to their former friend and landlord Benny, who plans to gentrify the block to the detriment of the artists and squatters living there.

While critic Hayley Levitt regularly rocks out to this unapologetic celebration of la vie bohème, critic Zachary Stewart sees Rent as a fraudulent glorification of urban poverty. You can read their debate here in our latest Point-Counterpoint:

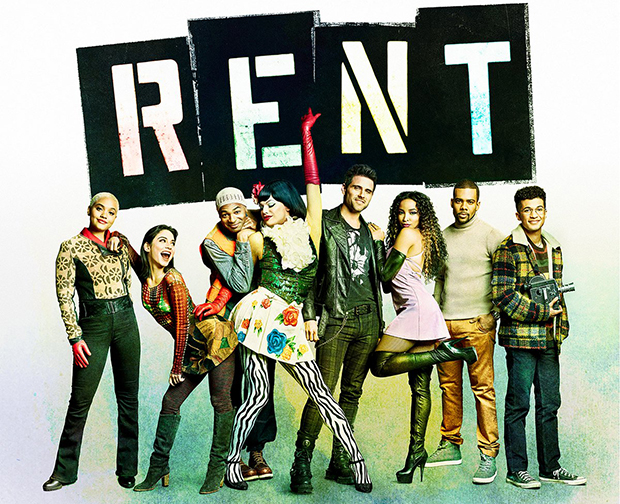

(© Seth Walters)

Zachary Stewart: Hi, Hayley. Why do you think Rent is a good musical?

Hayley Levitt: Oh boy, I have a feeling that means you don't think it's a good musical, so in honor of Fox's impending Rent: Live, I'll do my best to defend its good name.

I could talk about how Rent makes the story of the Puccini opera La Bohème accessible to young people and captures the punk-rock Bohemian culture of 1990s squatters on the Lower East Side. But honestly, when I fell in love with Rent as a teenager, I didn't care about any of that. The music just made me feel alive and loved, and I think that visceral reaction is a big part of what makes any work of art "good."

Zach: I agree that the music and the emotion it provokes is reason for Rent's status and longevity. Jonathan Larson was a talented songwriter, but a parade of great songs does not a great musical make. Rent regularly fails at the primary function of a book musical, which is to coherently tell a story. Too often the action stops so that the actors can serenade us from the lip of the stage, and rarely does it feel earned. Between the scream-singing and operatic emotion, it's easy to lose sight of the plot.

Hayley: The artsy, drug-infused, poverty-ridden environment is the core of Rent, not the moment-to-moment story. And if you told any Rentheads that the "Seasons of Love" moment is unearned, they would probably stone you in the street.

Zach: That angsty poverty fetishism is what I like least about Rent. It purports to spotlight the story of marginalized people living with AIDS, but drifts at every turn to the story of Mark: an upper-middle-class dude from Scarsdale who could easily escape his squalor (or at least pay his rent) if he would just answer the phone when his mother calls. The central conflict isn't even about AIDS or militating for adequate health care, but two white "artists" who feel like it is their right to bilk their black landlord. That entitlement is expressed in the screechiest, most adolescent manner possible. Is it any wonder that Rent has found its most fervent fan base among suburban teenagers? This is a musical that masquerades as revolutionary, but is anything but.

Hayley: First of all, do you really want Mark to take money from his parents? That would be a far more egregious expression of white privilege than him dodging the rent — something that was par for the course on the Lower East Side in a time when the idea of "urban homesteading" made people feel an honest sense of ownership over the abandoned property they essentially developed like land in the Old West.

Second, Mark's role in Rent is to be the observer. He stays behind his camera (except for the brief moment he almost goes corporate) and takes in the community around him, which is essentially all Jonathan Larson could do. He was a white, middle-class, Jewish man from Westchester who, as a young adult, committed himself to a community of poor artists. This is the story that his own experiences allowed him to tell. If he had made something more akin to the revolutionary musical you have in mind, maybe it would have registered as insincere and we wouldn't be having this conversation today.

Zach: I can't speak for Jonathan Larson, but appropriating the experiences of the destitute people around him for his "art" is not all that Mark could do. Comfort is just a Metro-North ride away. And while taking his parents' cash would indeed be an act of privilege, it pales in comparison to the absurd privilege exhibited by turning his nose up at it. As you mentioned, Mark is even given the opportunity for gainful employment in his chosen field, but he walks away for fear of "selling out." Do you really think that any of the homeless folks in the tent city next door would reject such security? Unlike them, poverty is a choice for Mark. His storyline might as well be 2.5 hours of someone pouring Veuve down the commode.

Hayley: Let's lay off Mark. He's just one member of the tribe and he doesn't even really sing any of the good songs (sorry, Anthony Rapp). But no matter the privilege embedded in his (immature) refusal to get a job, this community of people is supposed to be actively buying into this way of life — not just floundering as victims of the system. They definitely are victims in a lot of ways — especially the characters battling AIDS in a city that was slow to respond to the health crisis. But they're supposed to be a bunch of anti-capitalist idealists who hate the man and live shame- and rent-free. That might not be an acceptable way to actually exist in the world, but that's why I'm watching a cathartic musical and not squatting in a tenement.

Zach: You're right to use the phrase "buying into" when discussing the lifestyle showcased onstage, a Disneyfied vision of urban poverty that can be easily consumed, digested, and expelled with a few tears. It signals social consciousness without actually challenging its audience in any significant way. That makes it more of a consumer product than real art.

Hayley: You don't think any of this was challenging for audiences in the mid-'90s? You have an HIV-positive drag queen, an interracial lesbian couple, and two heterosexuals taking "AZT breaks" at a time when AIDS was still being called a "gay disease." Then there's Maureen making terrible performance art and being a selfish human being while Angel goes and kills a dog for money. And yet despite all of that, you love these people, and you love that they love and support each other inside of this "utopia" they've built for themselves.

Zach: Alternative reality is more like it. I'm all for a musical that puts the real lives of people living with HIV/AIDS onstage, but Rent just isn't it. It's the Broadway equivalent of Mountain Dew: sugary empty calories that will give you a jolt of energy, but will become increasingly unpalatable with age.

Hayley: I think Rent is a perfect example of industrial designer Raymond Loewy's MAYA principle, which stands for "most advanced yet acceptable" — the idea that you satisfy a need while pushing the boundaries of expectation. At the time Rent was made, that's exactly what it did — just like Hair did before it and Hamilton is doing now. The baton gets passed along so each subsequent generation can move the goalpost a little bit further and plant its flag in the timeline of musical theater. Maybe Rent seems like empty calories to you today because we've spent 20 years consuming all of the nutrients it had to offer.

Zach: So should we expect a picked-over carcass to air on the 27th?

Hayley: It will be interesting to see how Rent is received by a national audience (and how Michael Greif will interpret the idea of "family viewing"), but my personal expectations are to feel a lot of feelings, swim around in my nostalgia, and delight in how many lyrics to "La Vie Bohème" I remember.

Zach: I'll be sure to stock up on the only things that will make the event bearable — wine and beer!