Hirschfeld, Kahn, Coleman: Theater Lives Worth Contemplating

Three new books and an art exhibit take a closer look at remarkable show-biz careers.

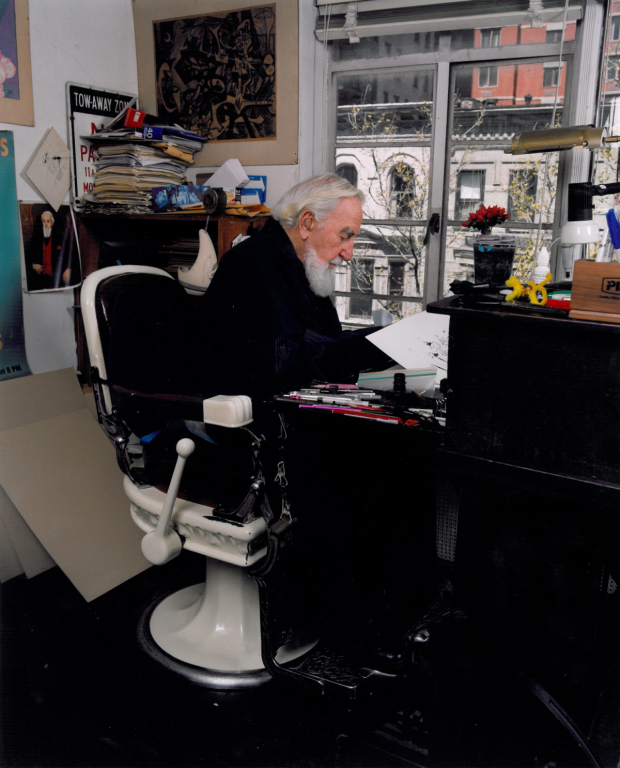

(© David Simson)

Virtually every morning for the last several decades of his century-long life, the caricaturist Al Hirschfeld went to the office in his brownstone on East 95th Street, sat down in the old-fashioned barber’s chair ("the last functional chair") he’d had installed at his drawing board, and went to work, sketching and drawing till lunchtime. Every artist in every field knows this to be the true story of art, though movie and TV biographies usually show it, if at all, only as a fleeting montage. Art is what you do every day, over and over again, concentrating on it till you get it exactly right, training yourself in it till the instinct becomes ingrained. The blank screen, blank page, or blank canvas; the bare rehearsal room, dance studio, music room; the stretches, the vocal warmup, the line run. Work is the artist’s raison d’être. You go at it, gruelingly, until it looks easy. Then the innocents out front will think it is easy.

We don’t do it just to impress the innocents. There must be something else, some impulse, some dedication, some drive, that makes this the most important thing in the world. People have described it as a vocation — a "calling" in the religious sense. Others prefer to call it love. I remember an incident, decades ago, when I was a student at the Yale School of Drama. Herman Krawitz, who taught theater management in the School and was Rudolf Bing’s second in command at the Metropolitan Opera, had brought Marc Chagall, who was then designing the Met’s new production of The Magic Flute, up to New Haven to address the Drama School students and those of the neighboring Art and Architecture School; the University Theatre was packed.

Chagall spoke only briefly, saying he had no remarks prepared, and asked for questions. Immediately, an art student in the front row jumped up and said, "Monsieur Chagall, how does a person know if he’s an artist?" Chagall spoke in French — he and Herman had brought along his translator from the Met — and what he said, as conveyed to us in translation, was this: "You get up in the morning, and you take all the love in your heart, and you pour it into your work. And if you do that every day, then you’re an artist."

This perturbed Herman, who, as a manager, was inevitably concerned with more mundane artistic matters, like which coloratura with a secure high C was available for five Lucia di Lammermoors in October. "But Monsieur Chagall," he expostulated, "what if you have all the love in the world in your heart, but you have no talent?"

Chagall looked at him sternly. "Ah," he said, "ce n’est pas possible." (That’s not possible.)

Thanks to some recent books, I’ve lately been pondering the lives people make for themselves in the theater. Chagall’s rubric holds true, I find, but it carries a dark underpinning that his sweet-natured words don’t immediately convey. To get up in the morning and concentrate on one thing, to locate all the love in your heart and pour it into that one thing — this is no easy task. In fact, it is a towering achievement in and of itself, no matter what results you get. Chagall didn’t say it would be easy. He merely said that if you did it every morning, you’d know that you were the one doing it.

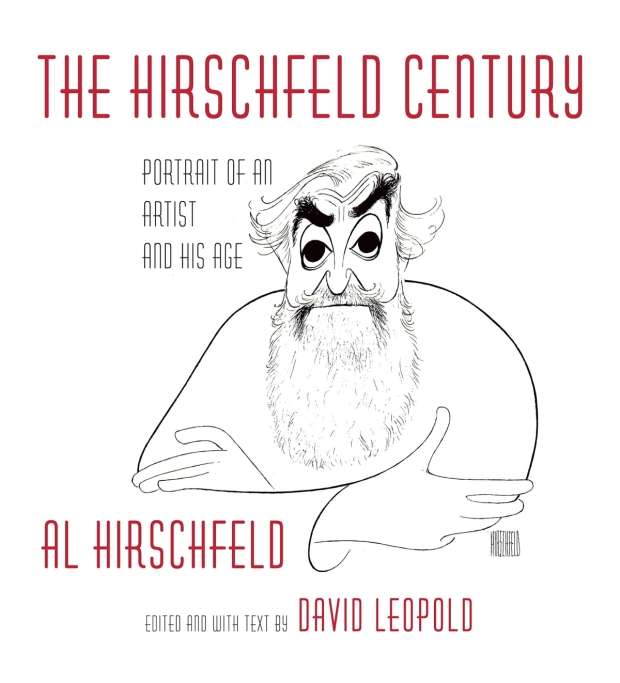

Albert "Al" Hirschfeld (1903-2003) exemplifies Chagall’s rule at its purest, and you can see the results in the current exhibition of his work, The Hirschfeld Century, at the New-York Historical Society through October 12, and in the accompanying book of the same name (Alfred A. Knopf), edited by the exhibition’s curator, David Leopold. Hirschfeld’s career was not precisely in the theater, but was most emphatically of it. A kid from St. Louis who loved drawing, transplanted to New York at age 12 to study art, he was immersed in theatergoing all his life. He tried many byways: His first adult job was as a commercial illustrator, designing movie posters and print ads for Selznick Pictures Corporation. He painted; he designed show posters and illustrated books; he drew political cartoons somewhat influenced by his great contemporary George Grosz, and by the radical cartoonist William Gropper. At the urging of his close colleague, Miguel Covarrubias, he visited Bali, where the blazing sun, he said, sharpened his line.

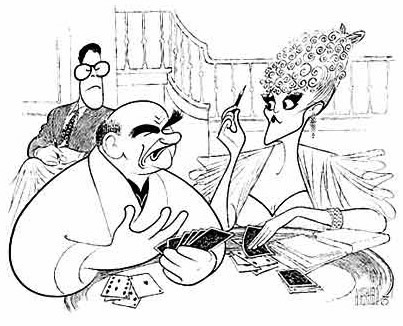

Hirschfeld drew many subjects beyond theater artists and scenes from shows: He drew political leaders, jazz musicians, writers, artists, speakeasy bartenders, movie stars, opera singers, talk-show hosts, and standup comics. He even cowrote, with his friend S.J. Perelman, the book for a famously disastrous attempt at a Broadway musical (Sweet Bye and Bye, closed in pre-Broadway tryout, 1946).

All of these, though, were only byways, streams that fed into or flowed from that mighty river, the theater, Hirschfeld’s consuming preoccupation. Through drawing every day, he refined his mastery of the line that had been burnt into him by the Balinese sun till he needed only the fewest brief strokes to capture on paper Carol Channing’s mouth, Gwen Verdon’s legs, the buoyant bulk of Zero Mostel. Some performers — and even some entire shows — have lodged in the public mind as Hirschfeld drew them.

This was his life, comfortable and regular, catching the theater’s flamboyant worldlings on paper as they flew past. He seems to have enjoyed it immensely. Perhaps he was wise to keep his dogged creativity on the outskirts of the art form he loved. Two of his innumerable subjects, the actress Madeline Kahn and the composer Cy Coleman, are also the subjects of recent biographies. I’ll have something to say about their struggles, which contrast sharply with the smooth line of Hirschfeld’s career, next week.

To read part II of this "Thinking About Theater" column, click here.

Michael Feingold has twice won the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism, most recently in 2015 for his "Thinking About Theater" columns on TheaterMania, and has twice been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Criticism. He serves as chairman of the Obie Awards and has also worked as a playwright, translator, and dramaturg.