The World Ends Not With a Bang but a Whimper in A Sign of the Times

From Founding Father to foundering father, Javier Muñoz takes on death, life’s meaning, and the universe in a new solo show.

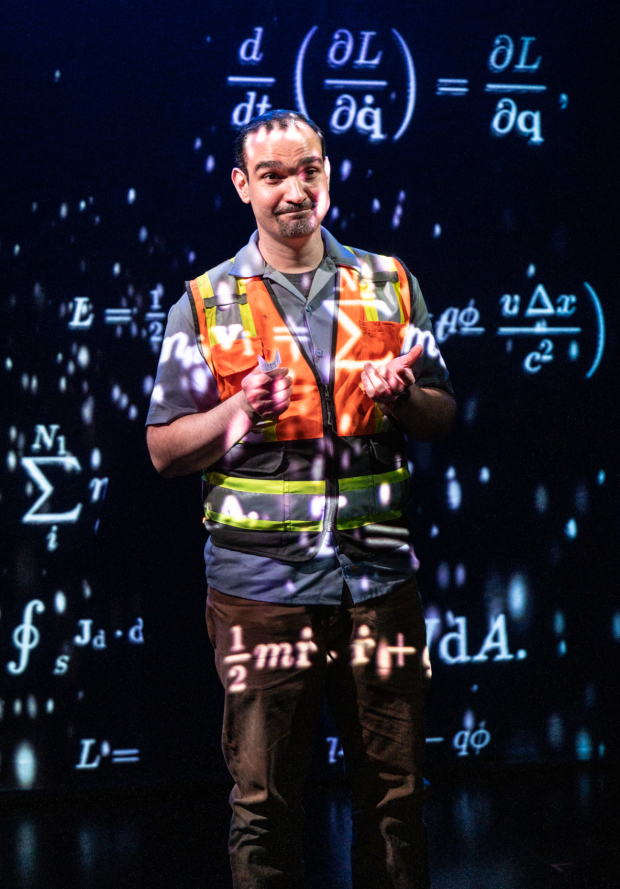

(© Russ Rowland)

A play that's billed as "the entirety of life in 95 minutes" has a lofty (read: unlikely) promise to fulfill. But yes, that's how Stephen Lloyd Helper's solo show A Sign of the Times, now running at Theater 511, is described in its blurb, and no, it does not live up to that boast, despite the best efforts of its star, Javier Muñoz (Hamilton).

"Lofty" does describe Helper's ambitions in his overwrought dramedy, which touches on subjects like the relation of love to grief, the nature of time, the meaning of life and death, the origin of the universe, the existence of God, and the agony of loss, while featuring quotes by people who had things to say about those topics, such as T.S. Eliot, Albert Einstein, and William Shakespeare. With all those heady ideas, it's no wonder that Helper's story loses its focus with a plot twist that spins the story from this world into a metaphysical black hole. If nothing else, the play does get us thinking anxiously about time.

Muñoz plays a nameless ex-physics professor who has traded in his mortarboard for a hard hat. He now works construction sites and directs trucks with a sign, which he calls "Fred," that reads Stop on one side and Slow on the other. He likes Fred's simplicity: If only everything were as binary and uncomplicated, he thinks. We learn that the man's change in profession was precipitated by a period of devastating losses: his son's death from cancer, his separation from his wife, his estrangement from a best friend. The comparatively simpler job of waving trucks by has relieved him of responsibilities but not of haunting memories. Then a freak accident suddenly gives him a glimpse of the afterlife where he is tortured by thoughts of things he failed to do.

(© Russ Rowland)

Helper, who also directs, begins his play with credible insights into the man's behavior as he stands at literal and symbolic crossroads. We quickly understand the man's desire to regain control of his life by reducing his experience to either/or problems. It's too bad that the story becomes almost as quickly mired in "big" questions that in this context begin to sound trite: If God exists, why is there suffering in the world? Is there such a thing as fate? Does anything happen for a reason? How much am I in control of my life? Helper's piling-on of questions like these leaves us so overwhelmed that by the end we're inclined to answer each with an indifferent shrug.

Of course, we don't expect any real solutions to these perennial questions. Muñoz for his part does convincingly show us a person wrestling with them, conveying with deep pathos the man's profound suffering at the loss of his son and subsequent alienation from his wife. But the play's heavy strokes of philosophizing nudge any feelings we have for this individual into the abyss.

The action is saved from protracted monologue by Kristen Ferguson's trippy projections, which give us a peek into the man's brain by showing us images of cosmic vortices, mathematical formulas, and images of Einstein and Shakespeare. Likewise, David Van Tieghem's sound design breaks up the philosophizing with intermittent rumblings of trucks passing through, as well as an unintelligible, terrifying "voice" of a celestial being whom the man encounters during his otherworldly sojourn. If that's what the next life sounds like, heaven can wait. But like the man next to me who prematurely whispered "Is that it?," you might not be able to.