Review: Tambo & Bones Will Make You Second-Guess Everything You Do in a Theater

(© Marc J. Franklin)

"Imma put on a show!" says Bones (Tyler Fauntleroy), one of our two clowning characters who welcome us to set designer Stephanie Osin Cohen's conspicuously fake world of cardboard meadowland. "See, I tried to tell them a sad story. Appeal to they sense of Emily." The word Bones is searching for turns out to be empathy, a concept playwright Dave Harris is betting his audiences at Playwrights Horizons know heaps about— especially when it comes to the exalted world of tragic performance.

Tambo & Bones, now in its world premiere co-production with Playwrights Horizons and Center Theatre Group, takes our cherished principle of empathy — the very thing we like to believe separates arts lovers from the animals — and shines a big ugly spotlight on it until you don't just question your own moral virtue; you begin to wonder, "Should I even be here?" You'll certainly slink down a little lower in your seat with all the discomfort Harris and director Taylor Reynolds rain down in this unabashed mission to alienate audiences (certainly not a recipe for repeat customers). But if a play is judged by its ability to effectively communicate a message, Tambo & Bones gets the highest possible marks.

(© Marc J. Franklin)

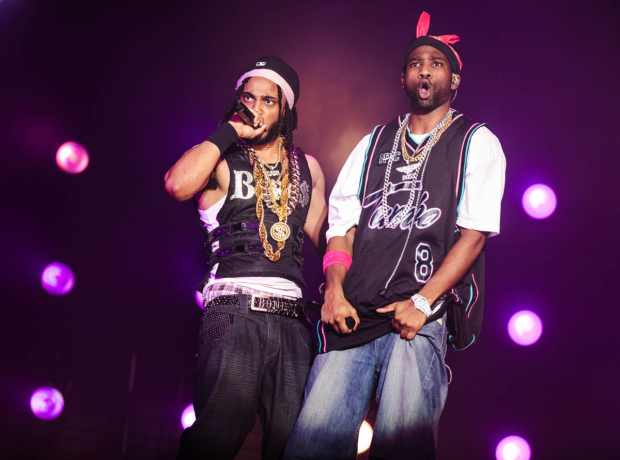

Separated into three acts, Tambo & Bones opens in what Harris irreverently describes as a "fake-ass pasture". Here, we find Tambo (W. Tré Davis) trying to resituate a two-dimensional tree for the sake of an ideal napping spot, while Bones solicits quarters from the audience on the back of a sob story about his fake son's birthday. Davis and Fauntleroy embody the tropes of old-fashioned clowning in every sense, from their exaggerated movements to their oversized, grime-encrusted outfits, buttoned with jaunty hats (Dominique Fawn Hill designs the costumes). With their easy charm and nonthreatening manner, they lure us right into our prescribed role as the audience, playing the laugh track to the antics of Tambo and Bones while resisting their transparent manipulations. That clearly concocted tale of woe won't work on us, we think to ourselves. Except, as Harris brazenly shows us over the ensuing 90 minutes, it already has.

In our first plot twist, Tambo and Bones discover they are the products of a minstrel show. Until now, their scripted environment has kept them ignorant and quarter-less, but not anymore. They're going to break out of their literal cardboard box and turn the world upside down, whether by delivering powerful treatises on race in America (Tambo's preference) or by making heaps of money and reclaiming control over the economic systems that have kept them smiling for pocket change (Bones's chosen strategy). Either way, their next move takes them right back to the stage.

(© Marc J. Franklin)

Of course, the conceit of a minstrel show is horrifically racist, and we're glad to be rid of it when Tambo and Bones reemerge in Act 2 as hip-hop artists, and very good ones at that (composer Justin Ellington, sound designer Mikhail Fiksel, and lighting designers Amith Chandrashaker and Mextly Couzin craft their very own version of a Jay-Z world tour). The question, however, becomes: What exactly are we rid of? When does the voyeurism of a minstrel show become a sanctioned artistic experience? When does a fanciful performance expose truths deeper than truth, and when is it merely capitalizing on a series of "fake-ass" stories? And who walks away with all that capital? Is it the artist who sold a piece of himself to a crowd of strangers, or the strangers who revel in their own virtue as they clap for the artist's pain?

It's a corrupt exchange, made only more corrupt by the fact that (as Harris repeatedly reminds us throughout the play) performances by Black bodies on high-class stages like this one are inevitably consumed by predominantly white eyes. And yet, we continue to sit there, laughing and clapping on Tambo and Bones's exuberant cues, only to be hit with unveiling after shameful unveiling of the crooked politics that underlie these theatrical customs.

It's a constantly shape-shifting production, and Davis and Fauntleroy keep hold of its fitful reins until the bitter end when Act 3 shoots us into a dystopian future that looks back on Tambo and Bones's lasting legacy (the remaining two cast members, Brendan Dalton and Dean Linnard, make auspicious appearances in this scene). Emotional whiplash is piled into these three disjointed acts that make bounding leaps from one to the next like a mechanical bull trying with all its might to shake the cowboy off its back. Tambo & Bones may not be the story that breaks free of its historical trappings, but Harris clearly will not be leaving the stage until he's at least broken a few cardboard trees.

(© Marc J. Franklin)