Review: Corsicana Invites Us to Listen to a Secret Song

Will Arbery’s newest play makes its world premiere at Playwrights Horizons.

(© Julieta Cervantes)

Ginny (Jamie Brewer) and Christopher (Will Dagger) are living together in Corsicana, Texas, in what used to be their mom's house. Mom is dead and Christopher is worried about the increasingly depressed Ginny, who has Down syndrome. Through a family friend named Justice (Deirdre O'Connell), he reaches out to Lot (Harold Surratt), a local sculptor and songwriter, to ask him to collaborate with Ginny on a song. That's the basic premise of Corsicana, Will Arbery's mysterious, meandering, and quietly subversive new play, now making its world premiere at Playwrights Horizons.

That plot description doesn't really do justice to a play that surprises at every turn. Just when you think you've figured out a heartwarming family drama about a brother and sister coming together following the death of a parent, Arbery hits you with a digression about the commodification of so-called outsider art, or a monologue about a suppressed memory recorded in a letter that might have been delivered by an angel, or a scene about rediscovering (against all reason) romantic love in one's 60s. Over the course of 2 hours and 30 minutes, Corsicana follows its own winding path, giving audiences the opportunity to look at the world from unexpected angles. This is surely the "weird art" about which O'Connell spoke in her Tony acceptance speech.

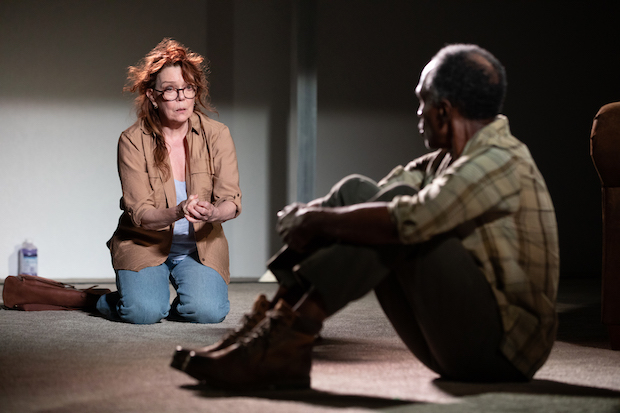

(© Julieta Cervantes)

"Everything is about our needs," Lot commiserates with Ginny. "All our little needs. Our special needs. Everyone around us becoming burdened by our constant need. And if there's something that we want? Well, it's for them to decide if we really need it." Bravely, Corsicana is a play that acknowledges the agency and sexual desires of people that still exist in the popular imagination as helpless and sexless — accessories to one's altruism rather than complete and dynamic human beings.

With a performance that is layered and occasionally furtive, Brewer demolishes the notion that people with Down syndrome could be anything other than complex individuals with idiosyncratic wants, interests, and emotions. Surratt delivers a similarly riveting performance as the kind of person who is practically invisible in our culture: an artist who creates with no thought given to career trajectory. Dagger has developed a genuine-feeling sibling relationship with Brewer, and he commands the audience's attention with a beguiling second-act monologue. O'Connell proves why she won that Tony with a performance that injects warmth and vulnerability into every moment. A combination of honest writing and revelatory performances makes it feel like we are watching real people onstage.

Sam Gold's deliberately restrained direction also does that, eschewing superfluous stage business in favor of showing two characters, feet planted, having a conversation. Actors rarely leave the stage, watching scenes from the periphery of Laura Jellinek and Cate McCrea's rolling shed of a set. Sometimes the actors extend the roof of that set out over the audience, inviting us into their world. At one point, after a particularly uncomfortable interaction, Lot closes an egress by pulling forward the upstage wall, and we understand that a part of him that he was only hesitantly sharing with the world is now off-limits. It's pretty devastating, as far as set changes go.

(© Julieta Cervantes)

Well-selected casual costumes by Qween Jean and spare lighting by Isabella Byrd contribute to a production that forces us to pay attention to Arbery's characters and what they are trying to communicate to one another. The most expressive moments arrive in song (Arbery collaborated with composer Joanna Sternberg), and it is a delight to sit and listen to the characters sing their thoughts and feelings.

Corsicana is the third play I've seen by Arbery following the magical time-warp of Plano and Heroes of the Fourth Turning, which depicted young conservatives at the precipice of national crisis (and which also made its world premiere at Playwrights Horizons). These plays feel like the work of three different writers, which is a testament to Arbery's expansive imagination and his ability to inhabit the voices of others.

Theatergoers looking for a straightforward plot driven by a thesis will be disappointed by Corsicana, a play that brings you in but refuses to do all the work for you once you're there. It's possible to walk away from the theater having several conflicting thoughts, while still not fully knowing if these are the ideas Arbery and company intended to convey. But with its embrace of the wonderous and unknown, Corsicana makes one thing clear: It's OK to not have all the answers.