Review: A Greek Princess Takes the Nude Pill in Antigonick

(© Neal Bennington)

Since the 1999 release of the dystopian action movie The Matrix, the metaphor of that movie’s “red pill” (taken by its protagonist to see the world as it really is) and “blue pill” (taken to remain blissfully ignorant) has entered the vernacular to denote a major revelation. To “take the red pill” could mean waking up to the machinations of global capitalism, or recognizing a system of family law that privileges women, or realizing that the Democratic Party takes Black voters for granted — depending on whom you ask. Lilly Wachowski, who created the film with sister Lana before both came out as transgender, has recently revealed that the “red pill” was intended as an allegory about gender identity.

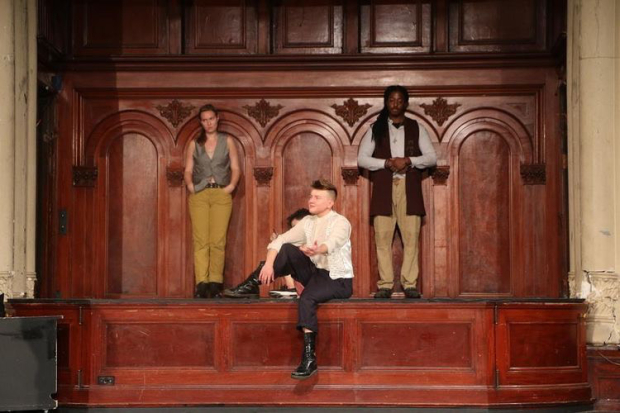

Great stories have a tendency to slip the surly bonds of authorial intent to touch the hearts of listeners wherever they might be. Such is the case of the Sophocles tragedy Antigone, recently presented by Torn Out Theater in a relatively new translation by Anne Carson called Antigonick. Competently directed by Britt Berke with few frills (and later, even fewer costumes), Antigonick leaves its audience with an open-ended question of what this tale of rebellion in the face of unyielding authority might mean in 2021.

The plot remains largely unchanged from the fifth century BC: Following the civil war between the sons of Oedipus which resulted in both of their deaths, their uncle Kreon (David John Phillips) has ascended the throne of Thebes. He honors the sacrifice of one nephew, but has decreed that the other should rot where he fell outside the city walls, and that anyone caught trying to bury him should be put to death. Their sister Antigone (Sophia Quiroga) openly defies her uncle-king. Despite warnings from the blind prophet Teiresias (an unsettlingly witchy El Yurman) and his own son, Haimon (Milo Longenecker), Kreon obstinately persists in his sentence — that Antigone should be buried alive.

(© Neal Bennington)

Founded in 2016 for the staging of a nude outdoor production of The Tempest, Torn Out Theater has built a reputation in New York with its (literally) stripped-down productions of Hamlet and The Rover. While a last-minute change of venues from Prospect Park to the Center at West Park has removed the outdoor component of the company’s style, Antigonick still uses the unadorned body as an instrument for unveiling the classics to a modern audience.

In this case, Antigone removes her vaguely Grecian gown (costumes by Ilana Lupkin) the moment she defies Kreon’s orders and decides to bury her brother. Mounds of dirt occupy the stage in Keyon Monté’s minimal yet earthy set design. A large stained glass window upstage reading “In Memoriam” (the building is home to an active Presbyterian congregation) is a silver lining to the move indoors, serving as a constant reminder of how we honor the dead and how we don’t. Following Antigone’s example, other characters disrobe during similar moments of truth. In other words, they take the nude pill.

Putting any naked body onstage is an act of defiance in our increasingly repressed age. But putting naked trans bodies onstage, as Torn Out has done here, feels downright revolutionary. With so many state legislatures taking aim at transgender Americans, it’s hard not to feel Antigone’s spirit of resistance coursing through this production.

Quiroga conveys that most acutely with a performance that is both powerful and vulnerable. Longenecker is similarly bold in his portrayal of Haimon, who becomes Romeo to her Juliet. Kaia Parnell is a haunting presence as Nick (as in “Nick of Time”), constantly measuring the stage and counting heads in the audience. Amy Elizabeth makes a memorable late appearance as Kreon’s wife Eurydike, managing to cut through Carson’s often-too-clever Brechtian alienation (she enters with the line, “This is Eurydike’s monologue it’s her only speech in the play”) to deliver real aching emotion.

(© Neal Bennington)

The most unexpected performance of the evening comes from Phillips, who portrays Kreon not as an adamantine patriarch, but a deeply closeted homosexual. And really, the two categories are not mutually exclusive. He seems to be viscerally disgusted by the thought of women’s bodies, spitting out his lines like a toddler would a Brussels sprout. It makes Antigone’s nude crusade feel all the more poignant.

A story as timeless as Antigone is elastic enough for this treatment, as every age redefines authority and revolt. To Seamus Heaney, Kreon was George W. Bush, while he was more Vladimir Putin in Ivo Van Hove’s imagining. Carson also provided the text for that 2015 production starring Juliette Binoche, but Van Hove insisted that she make an all-new translation just for him. One wonders when Kreon will be reimagined as a Belgian auteur.

As inspired as I was by Torn Out’s production of Antigonick, I left the theater thinking that there was an even more shocking way to tell this story: Antigone, a woman who ignores a state mandate for religious reasons, and who expresses that choice through the dramatic removal of a garment, isn’t a heroine well-suited for the modern progressive movement. I suspect that were she a real person in 2021, she would be an anti-vaxxer — a tough pill to swallow for theater audiences these days.