Our Shrinking Repertoire

New plays are fine (when they’re fine), but what about the great plays?

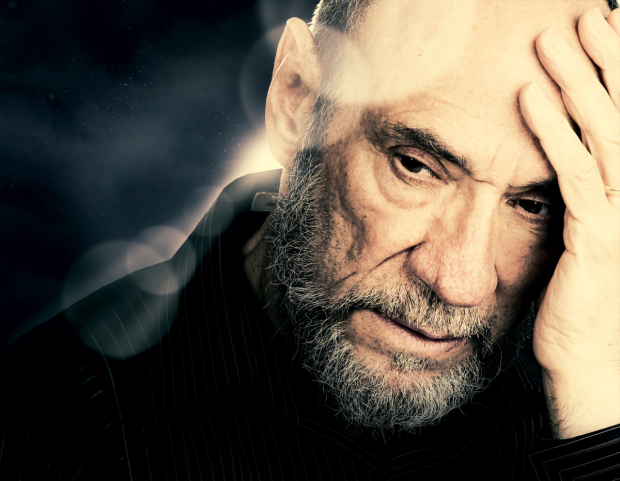

(© courtesy of Classic Stage Company)

A few weeks ago, I saw a bad production of a great play. I won't mention the play's title or the theater's name, because I like the people involved, I value their efforts, and I bear them no ill will. They chose to do a great play, they fought hard to do it justice — oh, how well all of us in the theater know that story! — and they didn't succeed, except in patches. But I won't write them off, and neither should you. After all, they aimed for greatness.

Naturally, the event set me thinking. Great plays do that. This one made me think about power and politics, about the state and the individual, about why we live and how we should live. But then, contemplating the frenzied flood of press invites to new plays in my inbox, I started to think about something else: the dearth of greatness within our profusion of productions. It sometimes seems to me as if today's theatermakers shy away from greatness, as if they had been actively discouraged from aiming for it.

A week or so after my great-play misadventure, I saw a rather good new play by a young writer — again I won't mention names. It was intelligently written, smartly acted and staged, and tackled a serious topic. I went away feeling that my time hadn't been wasted. But I did feel that something was lacking. The playwright's clever — maybe too clever — notion of who the characters were and how they interacted wasn't wholly credible, while the big serious idea came into the action through a gimmick that contained a major logical flaw, which none of the educated, highly articulate characters seemed to notice. The result, despite all the fine work involved, felt small and predictable.

Many such plays had already bothered me this year. Some were marked by uncertainty, on their young writers' parts, about how to shape and focus the work. That isn't necessarily bad in itself. Like all arts, playwriting is a process of discovering what you mean, not pre-deciding. These troubled and troubling plays often gave me more to take away than the irritating clever kind, in which you feel that the playwright has settled everything in advance, leaving nothing for you or the characters' to decide. Plays of both these types, if they catch the public awareness, can become commercial successes. But only playwrights of the first kind, sorting their way through our great uncertainties, are likely to achieve greatness at some point.

I had better try to explain what I mean by greatness. It isn't simply a matter of choosing a big ponderous theme, and spouting a lot of abstractions that will make academics write learned articles about your work. Nor is it a matter of an old play's having survived long enough to become a "classic," a term we use far too loosely. Any play that's over a certain age, or that's frequently revived, or that was written by an author famous for other, better plays can be called a "classic," but that doesn't necessarily make it one. Many fine plays live in these loose categories including some that indeed are classics — old plays worth reading or seeing for their own sake, not for their author's name or their age.

Such plays are worth seeing once in a decade, or in a generation. New York theatergoing has no shortfall in this area, thanks to the off- and off-off-Broadway companies who make such rediscoveries part of their mission. The Pearl, the Peccadillo, the Mint, the Metropolitan Playhouse, Red Bull Theater, and Classic Stage Company all exist to remind us that there is a world elsewhere of non-new, noncontemporary plays, full of works that can enrich our lives.

But these companies were mostly founded in a time when standard plays of acknowledged greatness got a regular hearing in larger venues: Circle in the Square was a go-to venue for Ibsen, Shaw, and Molière; the Roundabout tilted more toward classics than toward the commercial hits of yesteryear; the Vivian Beaumont was less often occupied by long-running musicals. So the smaller companies aimed more and more toward acts of rediscovery. I am not ungrateful: My theatergoing life is better for having included Susan Glaspell and Rachel Crothers, The Good-Natur'd Man and The Witch of Edmonton. But I want something more: I want greatness. And I think the public wants it too.

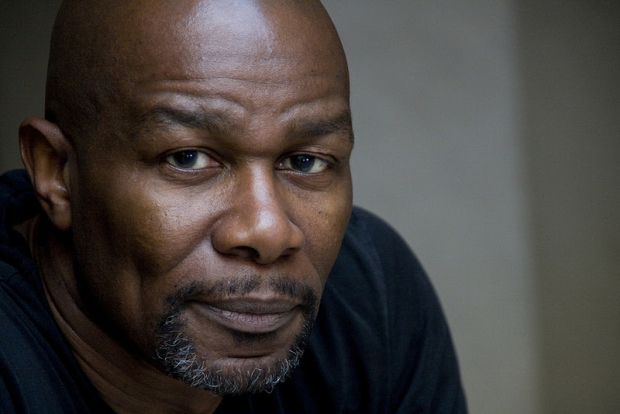

(© courtesy of Theatre for a New Audience)

A play with greatness in it attains the force and resonance of a myth; you feel it taking over you while you watch. One of the best descriptions of greatness I know is Eric Bentley's recollection of the first time he saw Strindberg's The Father: "Before the curtain had been up five minutes, I felt the unseen hand of the author had me by the throat." Anyone who knows The Father will realize that Bentley intended this graphic assertion to convey more than simple excitement. All good plays are exciting. But for a play that embodies an intellectual critique of life to grip you as The Father does, means something more: It means that the playwright has been able to seize your whole being — to seize you, as it were, spiritually by the throat.

We do not often get to see The Father. It will be back this spring, thanks to the good offices of Brooklyn's Theater for a New Audience, which is playing it in rep with Thornton Wilder's adaptation of Ibsen's A Doll's House. One reason we so rarely see The Father is that, like many plays of its stature, it makes people uncomfortable in a great way. New York audiences like their comforts. The Father's intent is to discomfit us out of all predictability. What it asserts about husbands and wives, parents and children, cannot be explained simply — or comfortingly.

Great plays can have many effects other than this deep discomfiture. Molière's The Misanthrope, Shaw's Heartbreak House, and Oscar Wilde's Importance of Being Earnest are comedies that, when played well, literally have a dizzying effect on our moral sense. What happens in them is wrong, outrageously wrong; we sit delighted by it. Each of these three works exemplifies a different aspect of our problem with great plays. We sacrifice Molière, when we produce him at all, to directorial gimmickry, Wilde to actor-camp, and Shaw to near-total neglect. New York's last Heartbreak House, at the Roundabout in 2005, was so pallidly staged I barely remember seeing it.

Which brings up the issue, vital on this topic, of play versus production. I'll have more to say about that — and about new plays with a touch of greatness to them — next week.

Part II of this "Thinking About Theater" column will appear next Friday, March 25.

Michael Feingold has twice won the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism, most recently in 2015 for his "Thinking About Theater" columns on TheaterMania, and has twice been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Criticism. He serves as chairman of the Obie Awards and has also worked as a playwright, translator, and dramaturg.