Meet the Tony Nominees: Gareth Owen Brings a New Kind of Sound to Broadway in MJ

Owen’s ninth Broadway show is a celebration of the music of Michael Jackson.

There's an old adage in the theater industry – you don't notice the sound design until it's bad. In MJ, it's the opposite: you notice the sound design because it's just so good. You can hear every instrument in the orchestra. You can comprehend Michael Jackson lyrics that you've been singing wrong for the last 30 years. And it's all thanks to its Tony nominated sound designer, Gareth Owen.

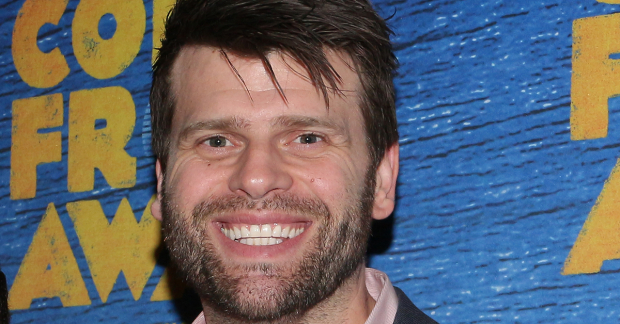

MJ is Owen's ninth Broadway show, and it's his third nomination. Here, he tells us about bringing a new kind of sound technology to the Neil Simon Theatre, and why he hopes it does the real MJ proud.

(© David Gordon)

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

How do you define your job as a sound designer?

I think the simplest way of defining it is that everything every single person hears within the walls of the Neil Simon Theatre is my responsibility. It's my responsibility that the audience can hear the music, can hear the dialogue, can hear the words over the music. It's my responsibility to make sure that the cast that can hear the music and each other. That the orchestra can hear the rest of the orchestra, the timing, and click tracks that keep all the video in sync. I'm also responsible for making sure that the video and lighting departments can talk to each other, and that the stage manager can hear what's going on.

I do a huge amount of what I think of as facilitation, making sure that everybody can do their jobs properly. I'm making sure that the producer doesn't have to give the money back to the people sitting at the back of the balcony because they can't hear the words, and I'm making sure that the orchestrator can hear all the details of the orchestrations, and that the lyricist can hear all the lyrics, and the book writer can hear the jokes.

And then, there's "I'm going to try and make this sound like a rock concert." Or, "I'm going to add some pretty reverbs or vocal processing to make sure the voices sound better." It's one of those things that I can go on and on and on about, and there are so many different aspects.

The absolute key thing is that I'm probably the only person who is involved in some way with every single other department being able to do their job. If the sound designer lets the show down, that affects everybody. We have fingers in every single pie.

What were your goals for MJ specifically?

Michael Jackson was so intense when it came to sound and music, so I found myself sitting there going "Would Michael Jackson be happy with this if he was sitting next to me?" But then there's the Broadway problem. Broadway likes to think that it likes the idea of a rock and roll sound, but it's always tamed down. What I was aiming for is for people to come out saying "I never got to see Michael Jackson, but that's the closest it could be," but without scaring the Broadway audience.

Throughout the whole process, Christopher Wheeldon, the director, and Lia Vollack, the producer, sat there with me and said, "We want this to be like a Michael Jackson concert." And I'm secretly sitting there thinking "Yeah, we'll see if you still think that come January." They never once lost their nerve. We never had that "Come to Jesus" moment after the third preview, after so-and-so's mother was in, which happens constantly. The number of times that people want a concept and then it turns out they really don't want it. That never happened. They knew what they wanted and left us alone to get it. No one ever lost sight of what they were trying to do.

Can you get into some of the nitty-gritty technical schematics of MJ?

We're doing things on MJ that have never been done before on a Broadway stage. We are using a new technology called wave field synthesis, which uses what is called the cocktail party effect. If you and I are standing having a conversation in a busy cocktail party, and there's music playing and lots of people talking…I can be talking to you like I'm talking to you now, face to face, but you can, if you choose to, defocus me, and start listening to what those two other people to your left are saying, even though I'm much louder and there's all this other noise in the room. Your brain can ignore me and start listening to them. That's the cocktail party effect. It's the ability of the brain to listen to different things. The only way the brain can do that is because all these different sounds come from different places and arrive at the head at different times.

A traditional sound system, like the one you're listening to me through now, is two speakers. And it's probably what you've got in your living room, and in your car, and when you put your earphones in. In a theater, there is a big stereo left and right, maybe with other speakers dotted around, but they all have basically the same sound in them, and as a result, your brain can't decouple what it's hearing, because everything is coming from two places. You become completely reliant on one choice of sound.

What we do is present a whole array of sounds spread across multiple speakers. What that means is, if you look at the ensemble, if she's singing and you look at her, you can hear her singing. Likewise, if you look at the guitar player, sound is coming from the guitar player.

Then, we've coupled that with tracking technology. Everyone on stage is wearing tracking technology, so the sound follows the performers as they move around the stage. If you've got a duet between Michael and his dad, the sound of Michael is coming from here, and the sound of dad is coming from there, and as they cross over, the sound is swapped, and we're using software to control it. And this is the first time it's being used on Broadway.

We're doing something in terms of a concert sound in the show that's never been done on Broadway, either, and that is not necessarily a result of me, but it's a result of the producers and director not losing their nerve and sticking to it.

We've never had a complaint about the show being too loud, and you would think that, considering how loud the show gets on occasion, we would have. But I feel like the audience for that show is knowing what they're getting into. We're never going to get to see Michael Jackson perform live anymore. Most of us are too young to ever have seen him perform when he was performing. So we're never going to get that experience. The closest we can give you is Myles Frost, who, let's face it, does a pretty damn good job.

Sound design is one of the theatrical jobs that no one really comprehends. What do you want people to know about what you do for a living?

What I've discovered is that if people aren't educated about sound, they just don't hear it. But, as soon as you explain it to somebody, they then become critical of other stuff they hear. So, if you, as a journalist, and me, as a sound designer, can educate people to start thinking about sound, it can only be good for the industry, because so many people just don't think about it.

We work hard to try and make sure it is as good as it possibly can be, but still, three-quarters of the audience doesn't know what an orchestration is. What they do know is whether they enjoyed the show. They may not know what percentage of the lighting contributed to that, or what percentage of the sound contributed to that. But in a show like MJ, all of the technical creative people are at the top of their game. You marry all that together and you get something that's pretty special.

I know it's Tony season and that's what everybody's worrying about right now, but just take a step back and look at this audience. Because that's who we're doing this for. They don't know that the lighting and video and sound are all tied together with time code and MIDI show control, that it's all linked from one go-button that the conductor presses when everyone's ready to go. They just know that they can see something coming in in the background, they're not sure what it is, and then you hear "Dah-dah!" and the whole thing changes and it becomes "Thriller." And nobody knows that, and they shouldn't. But what you do know in that moment is "Holy Shit."