(© Joan Marcus)

No one tells a story quite like John Leguizamo. The Hollywood star and human perpetual-motion machine has filled Broadway houses with his singular presence in his last three solo shows: Freak (1998), Sexaholix (2001), and Ghetto Klown (2010). His latest, Latin History for Morons, plays the more intimate Anspacher space at the Public Theater, where Leguizamo's performance has the effect of a firecracker in a closet.

While his previous shows have been mostly autobiographical, the subject of this one is Latin history, an interest that stems from Leguizamo's experience as a father: After a kid at school bullies his son with racial epithets, he confronts that kid's father, who calls Leguizamo a "PC snowflake." While this belligerent family (Leguizamo gives both father and son a pronounced lateral lisp) can point to a proud line of police officers, Leguizamo realizes that he cannot conjure a similar ancestry for his clan. This sends him on a quest to learn the history of Latin people in hope that he can find the perfect subject for his son's "hero project," a major presentation he will have to deliver to graduate eighth grade. For the next 90 minutes, Professor Leguizamo takes us back to school.

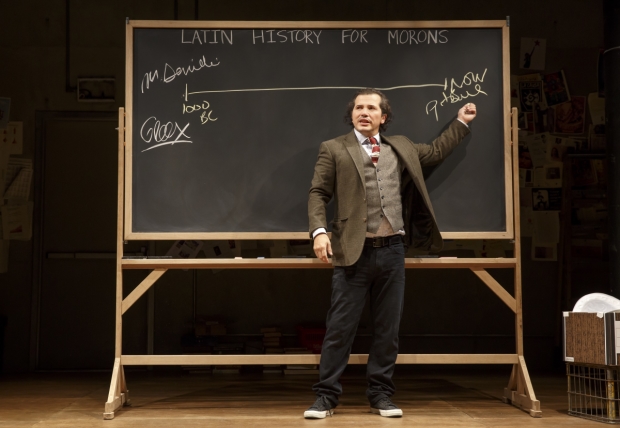

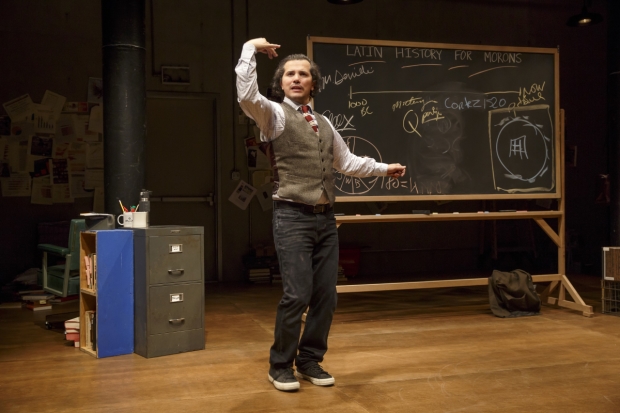

Set designer Rachel Hauck litters his makeshift classroom with a library of books on the subject: A biography of Simón Bolívar, a primer on Santería, and Michelle Alexander's The New Jim Crow are all visible in stacks on the floor in front of a rolling chalkboard, like a tangible bibliography.

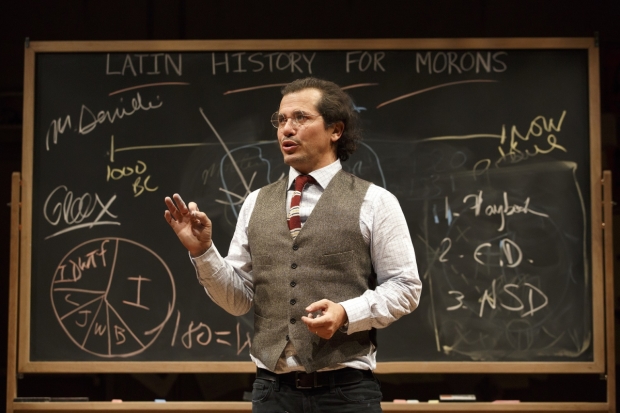

Leguizamo enters wearing a rumpled tweed suit and sneakers. His hair looks slightly disheveled, like he just jumped out of the shower and ran a comb through it before racing to class (excellent teacher wardrobe designed by Luke McDonough and Willa Piro). His appearance combined with the title of the show seems to promise the lesson on Latin history that we were denied in high school: the untold story of pre-Columbian ingenuity and the oft-ignored histories (at least in this country) of the modern states of Central and South America.

But Leguizamo also carries with him a dog-eared copy of Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel, portending the actual focus of this crash course: The cover art features the John Everett Millais painting Pizarro Seizing the Inca of Peru, a romantic rendering of the events covered in the most dramatic chapter in the book, in which 168 Spanish conquistadors defeat an Incan army of 80,000, capturing the emperor Atahualpa at Cajamarca.

Much of Leguizamo's monologue recounts such humiliating defeats for the native peoples of the Americas (a name that does not derive from any indigenous tribe or tradition of these two continents, but a Florentine explorer). While these events are central to the story of how 95 percent of the original inhabitants of the New World were exterminated, giving rise to today's Latin Americans (whose heritage is often a mix of European, Native American, and African), they are also the events with which audiences will be the most familiar. Worse for Leguizamo, it is difficult to find anything heroic in these stories to pass on to his son.

(© Joan Marcus)

Leguizamo always brings us back to this personal through-line, emphasizing the urgency of his quest. At 52, he is as physical as ever, dancing through the show and transforming into over 20 different characters (it is a marvel how he repurposes his jacket into multiple character-appropriate costumes). His vocal commitment is just as specific: He gives a spot-on impersonation of Garrison Keillor, who apparently sounds a lot like his therapist.

Tony Taccone directs a tight production that also leaves room for Leguizamo's wit and spontaneity. Alexander V. Nichols' lighting design and Bray Poor's sound design seem to spring directly from the performance onstage, never driving or overpowering it. Even if the history lesson disappoints, Leguizamo's irrepressible energy and supersize personality offer a perfectly satisfying theatrical experience.

(© Joan Marcus)

Near the end of the show, Leguizamo actually does touch on some lesser-known historic figures, like Loreta Velázquez, a Cuban woman who masqueraded as Lieutenant Harry T. Buford in order to serve in the Confederate army during the Civil War. Unfortunately, much of her story comes from her personal memoir, little of which has been independently verified. Perhaps Veláquez's story is more myth than fact, but the fact that we really don't know makes it clear that the subject of Latin history is one that has been neglected by mainstream scholars for far too long. In his own irreverent way, Leguizamo is making his audience question why that is.