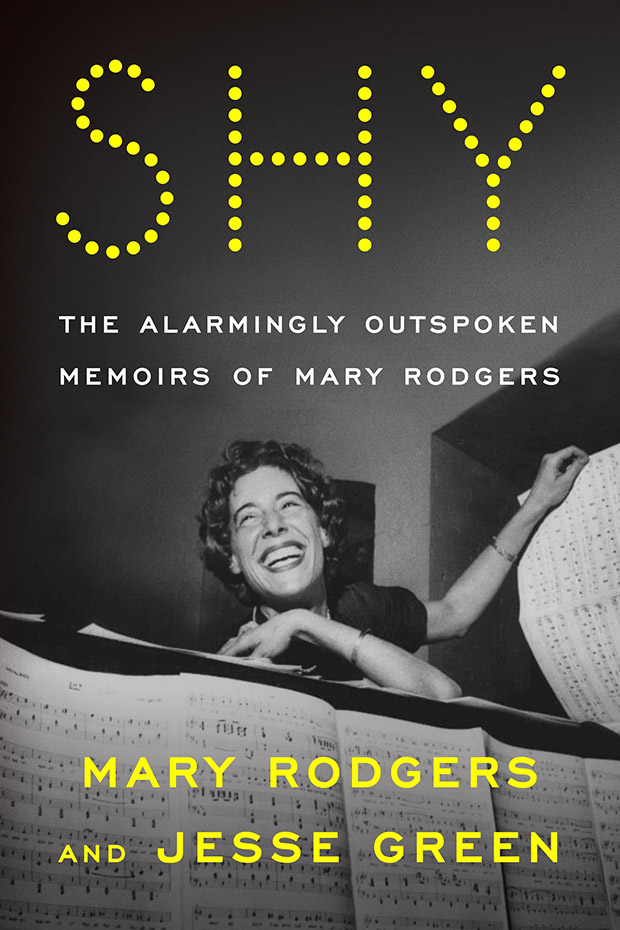

Interview: Jesse Green on Helping Mary Rodgers Write Her "Alarmingly Outspoken" Memoir, Shy

The frank and hilarious new book, chronicling the life of the ”Once Upon a Mattress” composer, is available beginning August 9.

It's got to be one of the most famous lines in theater history, and it's not even from a show: "Call me back when he's dead."

That's what Mary Rodgers, daughter of Richard, composer of Once Upon a Mattress, and author of Freaky Friday, told theater journalist Jesse Green when he asked her for a quote about Arthur Laurents (of Gypsy and West Side Story fame) for a profile he was writing.

Green didn't know it at the time, but that quote (and some other history with Rodgers and her family) would lead to a project that has dominated his most recent decade (along with, you know, his other job of being chief theater critic for the New York Times). With Rodgers, who died in 2014, Green coauthored Shy: The Alarmingly Outspoken Memoirs of Mary Rodgers, which hits shelves on August 9.

Shy, named for one of the songs from Mattress, is anything but. And here, Green tells us how it came together.

(images courtesy of the Rodgers-Beaty-Guettel Family and Earl Wilson/The New York Times)

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Did this whole book begin with Mary's "Call me back when he's dead" line about Arthur Laurents?

It wasn't the first step, but it was the second and more important step. The first step was around 2004, when I was assigned to write a profile of [her son] Adam Guettel when The Light in the Piazza was trying out in Seattle. I spent some time with Adam out there, and when I got back to New York, I called his parents to see if they would be willing. As I described in the book, they basically said "Come get all the trash." I showed up in their beautiful living room, and they, having no filters, told me lots of wonderful stuff, lots of inappropriate stuff. I wrote the profile, which they loved. I don't think he liked it very much.

We got to be, I wouldn't say friends, but friendly. I would hear these stories about Arthur Laurents, so I knew how she felt about him. So, I thought I'd see if she was willing to say something about him when I was writing a profile of Arthur at New York Magazine, and she thought about it and came up with the line you mentioned, which is now a classic. The irony is that when he did die, she didn't really want to say more at that time.

By that point, she had been asked many times to write her memoirs. As you can imagine, a good editor would assume that, given her voice, they would be wonderful. She had tried and was not happy with the result, so she rescinded the contact. Then she got convinced to do it again, and then she rescinded it again. It went back and forth for maybe 10 years. Finally, she called me and asked if I would do it with her. That was the only way she felt she could do it, for energy reasons and trying to get the kind of book she wanted, but also to work through those kinds of knots: What things do you say and do not say when your brand is unfiltered honesty?

Mary certainly was unfiltered – but more importantly, she has an openness to criticism of herself, her work, her family, that you don't see often from people of that generation.

She came from a family that were masters at repression and lying in public. I don't say that in a nasty sense. They had big problems with each other. From the way they spoke about it in public and in their multitudinous memoirs, you would never know that was the case, that Richard Rodgers as a compulsive philanderer and an alcoholic and a really cold fish; that her mother, Dorothy Rodgers, who was an impressive person in her own right, not only felt victimized by her husband but came from a family that fantasized its greatness and left her spending a lifetime trying to achieve it. That's the kind of sealed room Mary grew up in, and you can imagine that someone with her own ideas and talent would need to bust out of it in every possible way, which is what she did and never really regretted it.

The book is so self-deprecating in terms of her own work. Do you think she sold herself and her accomplishments short?

Yes. If you know her work and are among the few people who got to hear how it advanced as she got older — because most of us only know Once Upon a Mattress, which is exemplary comic musical-theater writing — she really did grow up, and most of what she grew into has rarely been heard. And some of it never can be heard. You could do cabaret numbers, but the shows that they're attached to cannot be performed. If you hear those, you really see that she was developing in some incredible directions and might have continued to do so, but she was multi-talented, and at some point, she said "They don't want me, so I'm gonna do something else." And she was able to have three very successful careers.

The arc of the book is really built around Mary's relationship with Stephen Sondheim — their friendship that started at childhood, her romantic infatuation that went unrequited, and her longstanding talent crush on him. Honestly, you learn more about Sondheim's life here than you do in a lot of books written specifically about him.

That was a whole issue. When I first told Sondheim I was writing with Mary, he said "Why would you do that? Who would be interested in that?" And I said, "Who wouldn't be interested in Mary?" And he said "I don't think we're interesting. I don't know why anyone would be interested in reading about me." And I said "Well, what do you think about her as a woman trying to do what you did at that time?" And he said "Ah, well, that is interesting."

As we began working together, the stories came out about her relationship with Steve, which began when she was a child and met him at Oscar Hammerstein's farm in Bucks County, where they were among the kind of tossed off orphans of other rich people, and carrying through to their young adulthood when they were apprentices together at Westport, and then in their little bit older adulthood where they actually, and I don't think anyone has ever talked about this, had a trial marriage of some kind. Very awkward, extremely embarrassing. But nevertheless, she was the one that wanted to marry him, and it was mostly adoration for his genius.

We were worried all along about what Steve would think about it, and she kept delaying talking to him about what was going into the book. Several things happened where I would check things with him, and I gradually began to realize that he didn't really remember anything. He was sharp as a tack on other things, but his memory was shot about those things.

There's a scene I love in the book. The Rodgers family had a house not far from Westport, and Steve and Mary would spend a lot of time there, and they used to sit and talk under the Rodgers' pianos. That's where Sondheim basically came out to Mary. She's talking about somebody else who's gay, and he says, "I think I may be that way too," and she says, "You know, they can fix that now." And he says something like "I don't know if I want to fix it." For someone of my generation, just the placement of that scene underneath the Steinway grand on which Richard Rodgers probably wrote South Pacific is just too much.

Had she seen any of the book before she died?

The only part that she had actually seen was the first little section called Hostilities, about all the games she played in the course of her life, and she felt it wasn't mean enough. So I said "Mary, you burn like seven or eight people in one sentence half the time."

I was surprised reading that the only person she didn't care for more than Arthur was his husband.

She had a lot more to say about that that I did not put in. There's a five to 10 percent factor where I said no. Even with the "Call me back when he's dead," she recognizes her hypocrisy. By being afraid to be the victim of the things she saw him doing to other people, she abetted his doing those things and, in essence, stood by as he misbehaved. Finally, it turned on her and people she really loved so much that she couldn't ignore it anymore and she cut him out, and presumably got thrown into that box of photographs he kept of people who he didn't talk to anymore or who didn't talk to him.

But I don't think there's anyone that she sees only in one light. Even her mother, who is kind of the monster of the book, more than her father, who she completely forgives because of the gift. Her mother was pretty awful to her, but she still has great admiration for her and understands the trap she was in, just as she has to forgive herself for the trap that she herself is in. The book is not mean, in my opinion, even though she wanted it to be meaner. It's just frank.