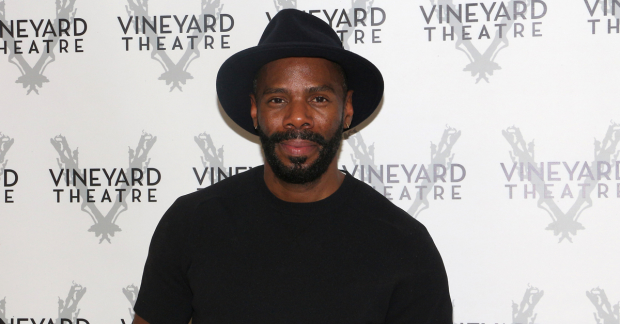

Here's Why You Haven't Seen Colman Domingo Onstage Lately

The Tony nominee wants to shake up the world with his artivism — and he’s doing it often from behind the scenes.

It's been a while — a long while — since Colman Domingo took the stage in New York City. After establishing a Broadway career that included two short-lived but groundbreaking musicals, Passing Strange and The Scottsboro Boys, and an off-Broadway foothold that introduced his work as playwright (Dot, Wild With Happy), Domingo made the move out West to look for projects that satisfied the man and his soul.

As a result, we've seen Domingo onscreen in projects that challenge him and change the cultural conversation in the process. On projects ranging from Fear the Walking Dead to If Beale Street Could Talk, Domingo is making his mark on the big and small screen, even though his heart is still in the theater — if not onstage, then behind the curtain.

At the Geffen Playhouse, Domingo is now the coauthor (with Patricia McGregor) of Lights Out: Nat "King" Cole, a "dazzling and devastating and subversive" bio-musical about the iconic American singer featuring Dulé Hill in the title role. Cole's struggle, Domingo discovered, mirrored his own, and it taught him an important dictum to live by: in order to make a difference in the world, you have to "tap it out so hard that your feet bleed."

(© David Gordon)

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

What is the origin story of Lights Out?

We had a commission with People's Light Theater Company. I did some research on Nat King Cole, and I started to get increasingly frustrated. I found that everyone said that Nat King Cole was the epitome of grace, especially grace under fire. There had to be more than that.

I stumbled on some episodes of his television series in 1957, and I became fascinated. The show started to hemorrhage money because it couldn't get a national sponsor. He was the most successful entertainer of his time, but advertisers were so afraid of the pull of the South that they did not invest in his show. He continued to invest in it because he knew that it was a long-term plan, if not for him, then for the next Nat King Cole to come along and make a difference. I thought that was a quiet act of revolution. That's where I found the underpinnings of the show: What if we deconstruct Nat King Cole and the American dream to find out who we are now?

I asked Patricia McGregor to join me, and we wanted to make something that was dazzling and devastating and subversive.

In what ways is it subversive?

It invites you in with all the comforts and trappings that are uniquely American, and then we pull the rug out from underneath you. Our goal is to find a deeper meaning behind the man as he's wrestling with race and who he is in Hollywood and the music industry, and challenging him to be a bit louder about how he feels. It's not only about Nat King Cole as a performer, but it's about us, and how we can make a difference. For artists, our strongest weapon is our talent. To tap it out so hard that your feet bleed, you know what I mean?

You haven't acted in a New York show in a long time, but you've written several plays and musicals that we've seen here. Was that a conscious transition?

When I do theater, I want it to shake it up and burn it down a little bit, or I think, "What's the point?" This is such a great time for art because we're having conversations that we haven't had in many years, or put Band-Aids on, or never had. Now is our opportunity as artists to challenge our audiences in a deeper, more meaningful way, not just sit back and do something for the status quo.

Honestly, there are so few pieces of theater that are out there to shake up the world, and that's why I say no to a lot of theater. We spend such long hours to do theater, and more than likely, we're paid less than our worth. If I'm gonna do it, it has to be an act of artivism in some way. It makes sense that the things I've done are Passing Strange and Scottsboro Boys.

Does film and television offer more for you as an actor at this point?

Film and television have been offering much more in terms of the landscape of creativity and agency in the roles that I'm being offered. It also provides me financial stability. You go where the love is.

I've sold two television series. One is for HBO and is called Peaches, and it's about an all-female kickball league. Another is based on my play Dot, and it's now called West Philly, Baby. That's for AMC.

It's funny. My heart is so deeply embedded in the theater, but…To be honest, I've been part of successful shows in New York, but do they call me to say, "We want to produce your next piece of theater?" Strangely enough, they have a very short memory. These are theater companies that I have great relationships with, but I think a lot of the time, they want something new and shiny.