(© María Paz González)

Five balaclava-clad students fill the Public Theater's LuEsther Hall with the sound of revolutionary anthems in praise of Ho Chi Minh and the Sandinista Front. No, this is not an occupation by Marxist undergrads from the neighboring Tisch School of the Arts at New York University (although their pitch-perfect harmony leads one to suspect some musical theater training). Rather, it is Chilean writer and director Guillermo Calderón's frustrating and fascinating Escuela, now playing in the Public's Under the Radar Festival.

Performed entirely in Spanish (with English supertitles), the show revolves around a group of left-wing Chilean radicals in 1987, during the waning days of the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. They meet in a secret location to train for their popular revolution. Designer Loreto Martínez's shadowy lighting makes this underground safe house feel authentically furtive, even though his set features only some nonthreatening furniture facing a small chalkboard. Living up to its name, Escuela teaches us a lot of things we Americans should really know more about, like the 1973 CIA-backed coup against Chile's democratically elected president, Salvador Allende. It also teaches us things no one should know about, like how to take down an electric transmission tower with a homemade bomb. Whether you consider this a revolutionary academy or an extremist training camp, everyone can agree that it is a strange kind of school.

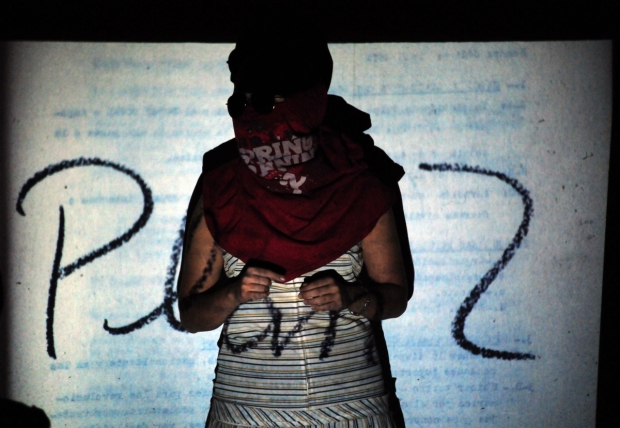

First of all, there's no designated teacher: Each student shares his or her knowledge with the group. Since the characters wear masks and are never named, I will refer to them by the color of their hoods. Green (Luis Cerda) knows about guns. Orange (Carlos Ugarte) is the communications expert. The ladies in red (Camila González and Francisca Lewin) teach the group about propaganda and Marxist dogma. Blue (Andrea Giadach) knows about bombs. They take turns leading the class, fielding questions and offering gentle instruction in their mellifluous Chilean accents. It feels a little like a Montessori school for terrorists.

(© María Paz González)

Calderón (the creator of 2013's Neva, also at the Public) is not afraid to mix humor into this incredibly dark subject. When Orange tells Blue that, should she die in service to the cause, they will paint a large mural of her face following the revolution, she sheepishly replies, "But how will you know what I look like if we never show our faces?" Over the course of 90 minutes, they never remove their masks (a challenge that this physically expressive ensemble easily surmounts). It speaks not only of their paranoia, but a persistent uncertainty about the sustainability of this clandestine lifestyle.

Calderón stages their discomfort in a very funny scene in which Green teaches them to shoot. It becomes clear that most of these folks have never held a gun before. Martínez slyly hints at the off-hours lives of these part-time guerrillas with his suggestive costumes. Most telling is the sparkly and finely cut dress on the red woman, who eventually admits to being an upper-middle-class university student.

During an extended monologue about her impending martyrdom, Lewin expertly musters the self-congratulatory tears of the communist bourgeoisie: She can push extra-hard for violent revolution knowing full well that she and her ilk will come out on top in any situation. Giadach gives a far more moving performance when she recalls Dani, a 16-year-old comrade who became an unwitting suicide bomber. One gets the sense that, like Macbeth, she is in blood stepped so far that returning would be as tedious as going over.

In truth, they all are. Ever-provocative, Calderón leaves us with an unsettling question: What happens when people have prepared for years to commit political violence, only to find that violence unnecessary in changed circumstances? Twenty-nine years later, the proletarian revolution they yearn for has not come to pass. Instead, a 1988 referendum heralded the return of democracy to Chile. González's character contends that this referendum only serves to legitimize Pinochet's exploitative economic policies. Still, despite her current unpopularity, few would accuse Chilean president Michelle Bachelet of running a dictatorship. Of course, with the right amount of passion, people can see all manner of malice in a seemingly innocuous politician (just ask Barack Obama).

Marked by doubt, Escuela cautiously probes the cloudy threshold between fervent belief and deadly action. The show makes an excellent pairing with Chris Thorpe's Confirmation, which explores the opposite end of the political spectrum and the impulse to reinforce our own sense of righteousness with a selective examination of the facts. Considering the universality of that instinct, it is safe to say that the anonymous terrorists of Escuela are not as foreign to American society as we would like to think they are.