Capitalists, Nazis, and The Damned

(© Stephanie Berger)

Perhaps you know someone who justifies his complicity in the most malignant politics because it's good for the pocketbook. Baron Joachim von Essenbeck (a sad-eyed Didier Sandre) is just such a person. He's the patriarch of the German industrialist family at the center of The Damned, Ivo van Hove's staging of the Academy Award-nominated screenplay by Luchino Visconti, Enrico Medioli, and Nicola Badalucco. It is now making its breathtaking North American debut at Park Avenue Armory, the halls of which seem destined to be haunted by the dark spirits this play conjures.

The Essenbecks are a thinly veiled reference to the Krupps, the Junker family whose steel mills and arms factories were essential to the Nazi war machine. Their story begins on February 27, 1933, the evening of Joachim's birthday celebration and the night the Reichstag goes up in flames, giving the Nazis pretext to solidify control of the government. Joachim finds them personally distasteful, but sees good relations with the state as essential to the health of the firm. His son Konstantin (Denis Podalydès) is active in the Sturmabteilung (SA), making him a natural to replace the anti-Nazi Herbert (Loïc Corbery) as vice president. Sophie (Elsa Lepoivre playing the widow of Joachim's beloved first son) and her boyfriend (an oily Guillaume Gallienne) greet this reshuffling as an opportunity to improve their own fortunes. This kicks off a family power struggle that makes Game of Thrones look tame by comparison.

(© Stephanie Berger)

The story churns forward with the brutal efficiency of an assembly line under Van Hove's unrelenting direction. Jan Versweyveld's set occupies the width of the Wade Thompson Drill Hall and lays the whole process bare: from dressing room vanities stage right to a neat row of coffins stage left. Eric Sleichim's nerve-racking sound design captures the industrial grind of the play, while An D'Huys's costumes direct our eyes through the strict control of color, like when Matin dons a patterned kimono as the rest of the family wears formal black and white. Tal Yarden's video design, projected on a large upstage screen, also does that through the frame of the camera. The Damned is essentially a live film, with close-ups and dramatic angular shots accenting the austere mise-en-scène.

Several times, Van Hove and Yarden trick us into believing we're watching live video when the moment has actually been prerecorded. This cinematic gaslighting reaches its apex with an unforgettable depiction of the Night of the Long Knives. Onscreen, we see a large group of men gathered for an SA retreat charged with the kind of exaggerated virility and homoeroticism central to such fascist organizations. We see this phalanx of proud boys getting drunk and removing their uniforms before careering down what can only be described as a Nazi slip 'n' slide. Yet in the physical space, we only see two men, Konstantin and his young valet (Sébastien Baulain), who also appear onscreen. The precise coordination between live and prerecorded performance is not only a testament to Van Hove's resourcefulness, but also his rigorous commitment to stagecraft.

(© Stephanie Berger)

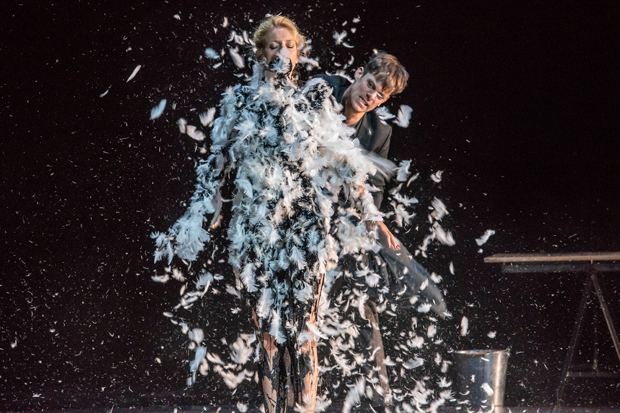

The performances are crucial in selling Van Hove's most arresting moments, and this cast wholeheartedly rises to the task. Lepoivre gives an emotional performance that almost succeeds in convincing us to forget how much her character (a cross between Gertrude and Lady Macbeth) contributes to this story's destructive conclusion. Clément Hervieu-Léger delivers a heartbreaking portrayal as Konstantin's sensitive and artistic son, Günther. Far less sympathetic is Éric Génovèse as Aschenbach, the neighborhood SS officer: Mephistopheles in a black suit, he methodically plots the family's implosion by appealing to each member's preexisting greed and vanity. When he trains his cold, dead gaze on the audience, it is truly unnerving.

Then there's the legitimate heir to the Essenbeck empire and the play's dark soul, Sophie's son Martin. Christophe Montenez embodies him with a psychotic fervor that is simultaneously impressive and also the play's biggest misstep: We first encounter Martin wearing high heels and black vinyl gloves as he menaces his family with a baseball bat. He's like something out of The Silence of the Lambs: We know he's a psychotic from the beginning, so it's not particularly surprising when that's what he turns out to be. It would be far more dramatic to form a first impression of him as a benign clown (as Helmut Berger plays him in Visconti's film) before coming to the creeping realization of what he really is: an amoral yet powerful man whose disturbing sexual proclivities and vulnerability to blackmail make him all the more valuable to the world's most nefarious manipulators.

(© Stephanie Berger)

Of course, the resemblance of the protagonist to our president isn't the only thing that will give you pause at The Damned. Van Hove has staged a nightmare from the darkest recesses of humanity about the obscene madness that can result from so-called rational self-interest. It unashamedly says, No, your stock portfolio isn't the only thing that matters.