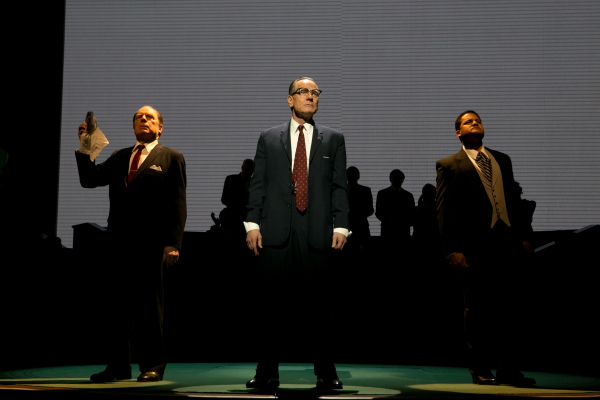

All the Way

”Breaking Bad” star Bryan Cranston makes his Broadway debut in this fast-paced political thriller about the first year of Lyndon Johnson’s presidency.

(© Evgenia Eliseeva)

Upon entering an African-American home in the 20th century, it was not uncommon to see three portraits hanging on the wall: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Jesus Christ, and John F. Kennedy. While Kennedy was an undoubtedly gifted orator, his legislative and policy record on civil rights is remarkably slim. It wasn’t the handsome young president from Massachusetts who passed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, but his successor, a foulmouthed modern Machiavelli from Texas: Lyndon Johnson. Where’s his portrait next to Jesus? Where’s the love for LBJ?

Robert Schenkkan reexamines the 36th president’s record in All the Way, now making its Broadway debut at the Neil Simon Theatre after earlier presentations at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival and American Repertory Theater. Schenkkan has talent for exploding the two-party paradigm and showing American politics for what it really is: a multifront war between interest groups with constantly shifting alliances; or, as Johnson might say, "It’s a knife fight in a dark room with a slippery floor." All the Way isn’t a glowing bioplay or glorified excuse to trot out Johnson’s greatest one-liners before an audience (although there are plenty of those), but an intimate look at the process of legislative sausage-making: the good, the bad, and the extremely ugly.

The show begins shortly after Kennedy’s assassination and Johnson’s airborne oath of office. It’s roughly 11 months before the 1964 presidential election, and Johnson wants to pass the Civil Rights Act before Americans go to the polls. LBJ (Bryan Cranston) engages in political horse trading and copious profanity, occasionally stopping in an aside to teach us something about the nature of Washington: "Everybody wants power; everybody. And if they say they don’t, they’re lyin'." Ever the Texas cowboy, he wrangles the competing interests of men like J. Edgar Hoover (a deliciously passive-aggressive Michael McKean), Robert McNamara (a pushy James Eckhouse), Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (Brandon J. Dirden in a deeply complex performance that gets beyond the sainted mythology of King), and Governor George Wallace (Rob Campbell at his smarmiest). "I think he actually enjoys being the turd in the crystal punchbowl," remarks LBJ on the latter.

For political junkies, All the Way is the equivalent of a three-hour bender. Cranston gives us a Johnson at the top of his game: He’s sharp-witted, never missing a beat…or an opportunity to gain advantage on an opponent. Yet as we get into the second act, which focuses on the election, LBJ is increasingly beleaguered. (Don’t all American presidents seem a little depressed?) Every inch of Cranston’s demeanor and physicality shows us a president weighed down by the office and the knowledge that his passage of the Civil Rights Act has divided his party, ceding the once firmly Democratic American South to the Republicans for a generation or more.

Spoiler alert: He wins the election anyway, although (and this is a minor quibble) Schenkkan seems to attribute this to Johnson’s earnest oratory more than the Cold War politics of fear that likely secured his victory over Barry Goldwater.

A lot of the drama takes place over the phone. Director Bill Rauch has staged these conversations (in different offices, sometimes hundreds of miles away) on Christopher Acebo’s large polished-wood set that serves church pews or congressional benches, depending on the scene. While at first this seems like a clunky choice, new space springs eternal all over the stage and beyond. Protestors and political conventioneers mingle in the aisles of the theater. Scenes overlap in a way that expands the scope of the play far beyond the immediate location. For instance, as Johnson receives reports from the Gulf of Tonkin in the Oval Office, two FBI agents dig in a Mississippi field for the bodies of slain civil rights activists. As Johnson orders the air strikes that will lead to the Vietnam War (seemingly to deflect Goldwater's criticism that he is "soft on the military"), the gravediggers place a corpse directly at his feet.

Undoubtedly, some will find All the Way a damning indictment of American government, in which vote counts and party loyalty trump good policy every time. Yet isn’t a complex and contentious system of competing interests far more representative of American society than a technocratic consensus? At the very least it makes for better theater. Near the end, as if sensing the distaste in the room, Johnson turns to the audience and asks, "Did it make you feel a little squeamish? Did you have to look away sometimes?" In all honesty, Mr. President, my eyes were glued to the stage.