Op-Ed: The Nonprofit Theater Industry Can't Just Do the Bare Minimum Anymore

One play by a BIPOC writer per season does not make diversity.

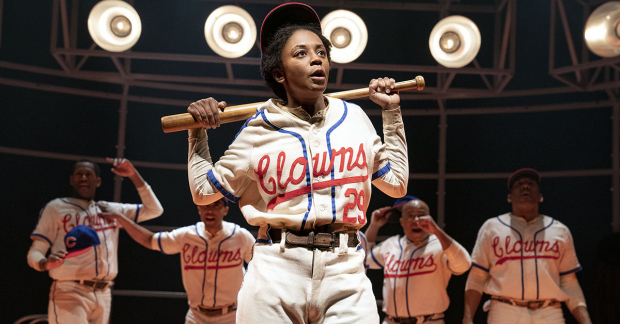

(© Joan Marcus)

There's this concern I have. And as a professional audience member, it's been on my mind a lot lately. I'm concerned that the nonprofit theater industry won't learn. In the decade that I've covered theater, I see that the industry has become content with patting itself on the back and making gestures — but it hasn't learned.

What annoys me is the industry's self-delusion. Theaters think that because they produce a play each season by a BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, Person of Color) artist, they've done enough. They think that because they commit to "colorblind casting" a 50-year-old play, they've done enough. They think that because they've done an all-Black production of a white classic, they've done enough. They think that because they've sent out a statement of solidarity, they've done enough. They haven't done enough. They never have. Not by a long shot.

It's no secret that most of New York's monolithic nonprofit theaters are run by the same people who've been in their positions for decades. It's no secret that they are mostly the same gender and skin color. They're the people who've produced Pulitzer winners and helped shepherd their companies into multimillion-dollar, state-of-the-art venues that still have too few bathroom stalls for female-identifying audience members.

They're the ones who sent out Black Lives Matter solidarity statements but only seem to produce one show each season by Black or Asian or Latinx or Middle Eastern playwrights. (It's always "or"; it's never "and.") These plays always seem to be produced in venues with monikers like "Stage 2" or "Black Box" attached to their names.

The fact of the matter is, you can count on two hands the total number of BIPOC writers produced in the last decade on the main off-Broadway stages of Roundabout Theatre Company, Manhattan Theatre Club, and Lincoln Center Theater combined. That total dramatically increases when you look at their smaller venues.

You know they think they've done enough because their season announcements tell you so. If they didn't think they'd done their job with just one play — one — by a BIPOC artist each season, they'd theoretically produce more. They'll feel like their diversity mission is accomplished because that production got rave reviews, the kind of notices they hadn't seen for their productions about affluent white families fighting in their spacious pied-à-terres.

(© T Charles Erickson)

But then they'll just go back to putting on those kinds of plays, the ones that get mediocre reviews and walkouts at intermission, because it's easy. It's safer than producing work that will lead to hard conversations that no one seems equipped to have because the managerial staff at most of these nonprofit theaters is collectively white. I've interned at these companies. I've seen what their rehearsal rooms look like at press events, and what kind of crowds they draw on opening nights.

Awards nominators will have to sit through the pied-à-terre play five times a season at most every nonprofit theater in New York City. I know from experience. I'm president of the Outer Critics Circle, one of the main awards-giving bodies for Broadway and off-Broadway theater. We collectively hate these plays. These plays largely inspire nothing in us but a desire to never go to the theater again. You can tell by their body language that the paying audience does too.

But then we'll see a play in a "Stage Two" or an "Upstairs" or a "Black Box" that was written by a Black writer, or an Asian writer, or a Latinx writer, and it will feel current and exciting and socially important. Not just that — it will feel like a play that will stand the test of time. We'll shout from the rooftops how good it is. We nominate it like crazy. And it won't win anything from us. It won't win a Drama Desk Award. Maybe it'll get an Obie.

How is that possible, especially for plays that are roundly praised? It's because our voters won't get to see the shows in the Stage Twos, which, as we've already established, are pretty much the only spaces where theaters present work by writers of color. These spaces often seat fewer than 100 people, and with their patrons and subscriber ticket holds, the theaters just "can't offer tickets to multiple voting bodies." "It's physically impossible," we're told. "Financially, it just wouldn't work."

I've heard all of those excuses as I fought, often to no avail, to get my voters seated for plays like Ming Peiffer's Usual Girls and Donja R. Love's Sugar in Our Wounds and Jackie Sibblies Drury's Marys Seacole. For the theaters, the nomination is the win — they can use it in their promotional materials to get donations and federal funding. And if the shows are selling out, they don't need voters to come see it. For BIPOC playwrights, who are often relegated to the secondary spaces because they're continually viewed as "emerging" (and therefore, not yet ready for the primetime of the main stage), it's just another bit of unfairness. A nomination is good for writers, but a win could lead to a stepping stone that a nomination just couldn't.

There are two ways these theaters can respond. The first is that they can put their money where their statements are. They can soul-search and hold themselves accountable by making changes. At the most basic level, they can commit to presenting more than one show a season by a writer of color. They can hire more diverse artistic teams and staff members. They can commission more writers of color with the multiple endowments that all of these theaters have. They can build a model that gets BIPOC artists in the room, in positions that aren't prefixed with "associate" or "assistant." As Rachel Chavkin said in her 2019 Tony speech, "This is not a pipeline issue. It is a failure of imagination by a field whose job is to imagine the way the world could be." These theaters can make it their mission and adhere to it and build the theater of the future.

Or they can do the bare minimum. They'll hire a diversity coordinator for a month and arrange an unconscious-bias workshop and add a board member who happens to be Black. Rather than program a play about an affluent white family whose long-simmering hatred comes to a head while they're sequestered during the Covid crisis, they'll choose the "woke" option and present a play about a Black family reckoning with current history instead. And then they'll just return to doing what they usually do, falling back into the same patterns they've always fallen into.

The second option is a very depressing thought, and it's not something that we can let happen. This is the thing that concerns me. These theaters have to institute the real change that they've been promising for decades. The bare minimum isn't enough. It was never enough. And hopefully, they've finally realized it.

Because once they do, then the great work will really begin.

(© Joan Marcus)

David Gordon has covered the New York theater industry for a decade. He is Senior Features Reporter at TheaterMania and President of the Outer Critics Circle.