In Akhnaten at the Met, a Pharaoh Juggles Revolution

(© Karen Almond / Met Opera)

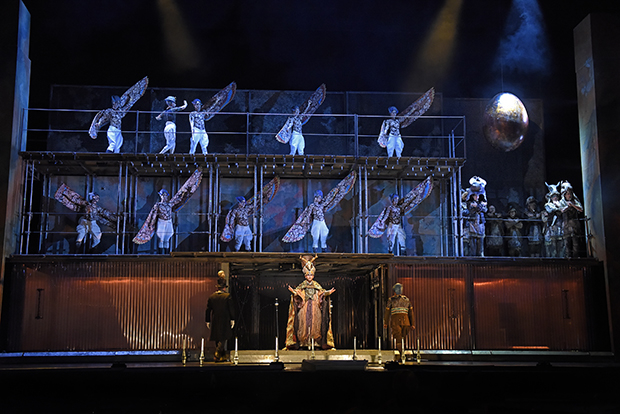

A ruler must keep a lot of balls in the air: security, justice, prosperity, faith. It's a juggling act that few leaders can perform well, with fewer still able to add variations to the routine without wiping out. If you think that's too blunt a metaphor for statecraft, consider director Phelim McDermott's production of Philip Glass's Akhnaten, which is now playing the Metropolitan Opera and features an ensemble of jugglers.

When it debuted at the Staatsoper Stuttgart in 1984, Akhnaten was the third installment of Glass's Portrait Trilogy about men whose ideas had a profound effect on the world (the other two are Einstein on the Beach and Satyagraha). Departing radically from the 20th-century settings of those earlier works, Akhnaten takes place in Ancient Egypt, a land that appears completely alien in this imaginative staging, even if the themes of the story feel uncomfortably familiar.

The opera opens with the death of Amenhotep III (Zachary James, who haunts the stage like the ghost of pharaohs past). As his son, Amenhotep IV (Anthony Roth Constanzo), ascends the throne, he announces his singular devotion to the sun deity Aten, scorning all other gods. With the support of his wife, Nefertiti (J'Nai Bridges), and mother, Queen Tye (Dísella Lárusdóttir sporting a powerful soprano), he changes his name to Akhnaten, attacks the temple of Amon, and constructs a new city on the Nile in tribute to Aten. But in his religious fervor, he neglects many of his sovereign duties — essentially, he drops the ball.

The juggling (choreographed with breathtaking complexity and precision by Sean Gandini) is not just an effective metaphor for the tragedy of Akhnaten, but also proves to be the ideal visual for Glass's music, with its rhythmic ostinati and arpeggiated triplets, constantly ascending and descending like jugglers' pins. As woodwinds and brass layer upon the strings, the routine becomes more complicated, with the balls flying just a bit higher as both the music and plot ratchet up in intensity.

Karen Kamensek conducts the score with an admirable balance of power and dynamic restraint. Every constituent part is clear, and every slight shift in the score is audible — often with hair-raising results.

The variations in Glass's score set the pace for McDermott's staging, as the performers creep across the stage in deliberate slow motion. Tom Pye's three-tiered set similarly seems to be always transforming, however slowly. The moon becomes the sun under Bruno Poet's transformative lighting, ushering in the age of Aten. Providing a frame for James's stentorian announcements, a box of light intermittently descends from the heavens, like a spacecraft from planet Robert Wilson (Glass's director for Einstein on the Beach). It is the most austere element of this sumptuous design.

(© Karen Almond / Met Opera)

Kevin Pollard's gloriously detailed steampunk-inspired costumes represent the star design element. Featuring heavy gold collars (ancient Egyptian), fur stoles (Victorian English), and gowns ornamented with doll heads (contemporary Gothic), they evoke bygone ages while creating something entirely new. It is unabashedly lavish, so that even as the performers move at a glacial pace, your eyes want for nothing.

Glass has been branded a "minimalist" composer, which is a misnomer. How could any composition with so many notes, presented with such dynamism and variation, ever be truly considered "minimalist"? The inclusion of a countertenor in Akhnaten harks back far more to the baroque than the minimal.

That highest of male voices belongs to Costanzo, and his notes soar above the stage, especially in his ethereal Hymn to Aten. He seems completely uninterested in earthly things, driven by a spiritual calling. His extraterrestrial sound and androgynous look (surviving depictions of the pharaoh are similarly gender-nonconformist) contrast with the bearded pharaohs that came before him. It also contrasts with his wife (Bridges possesses an earthly sexy contralto), most beautifully in their second-act love duet. When the queen has a lower voice than the king, we know we're looking at a full-scale revolution — not just in religion, but gender, art, and language.

(© Karen Almond / Met Opera)

Students of history will note that for every revolution, there is a reactionary movement, a timeless story that Pollard bracingly tells with his costumes: Nefertiti's father (Richard Bernstein) dons a top hat and tails, suggesting his mastery of money. General Horemhab (Will Liverman) wears a regimental uniform. The pointed miter of the high priest of Amon (Aaron Blake) wouldn't look out of place in Canterbury Cathedral (minus the animal skull decoration). These men represent capital, the military, and the church — three of the most important power bases of any society and the very figures Akhnaten has pushed aside for his revolution. Do we really expect them to take it lying down?

Revolutions rarely succeed in their first iteration, but they do influence subsequent generations: Glass nods to this by chasing Ahknaten's Hymn with a chorus singing the Hebrew Psalm 104 (which contains a whiff of holy plagiarism). Glass's music reflects that slow but sure pace of change, too: The seemingly static phrases are actually alive — ever-modifying, however incrementally.