Review: A Modern Masterpiece Arrives on Broadway With Pass Over

(© Joan Marcus)

When Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu’s Pass Over premiered in 2017 at Chicago’s Steppenwolf (where Spike Lee filmed it) and later ran at Lincoln Center’s Claire Tow Theater in 2018, America was a different place. We had yet to go through a life-changing pandemic, and white people had yet to realize that what Black folks had been saying for generations about the prevalence of police violence in communities of color was, in fact, true.

That second issue remains a main theme in Pass Over: The character of Ossifer (played menacingly by the brilliant Gabriel Ebert) is a manifestation of the kind of brutal, racist police behavior that we’ve now all witnessed. But while the first and second versions of Nwandu’s play had endings that depicted tragic outcomes of that kind of behavior, in the play’s new production at Broadway’s August Wilson Theatre, the tone and substance of the ending are significantly different.

Nwandu has turned her play from a disturbing tragedy into a troubling but hopeful tragicomedy. It is still a brilliant modern masterpiece that riffs on both Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and the biblical Exodus story, but this new production, directed again by Danya Taymor and starring the stellar Lincoln Center cast, shifts away from the deadly climaxes of the first and second productions and resolves with images of hope and reconciliation. In the wake of America’s witnessing of police murders of Black people, the play no longer has to show audiences that the violence happens; now it offers the possibility that change can happen.

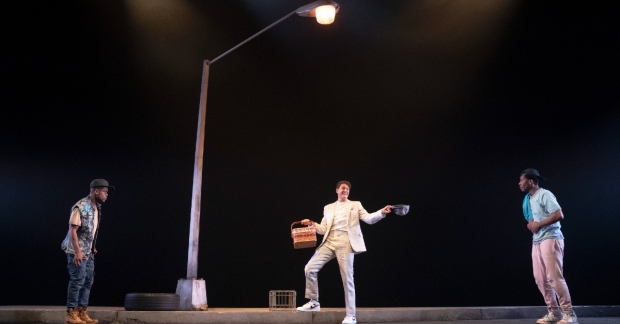

Jon Michael Hill and Namir Smallwood (both giving virtuosic performances) reprise their off-Broadway roles as Moses and Kitch, respectively, two young Black men living out their precarious existences on a dangerous street in a sparce urban landscape dominated by a tall streetlamp (Wilson Chin’s bleak, ominous set suggests the play’s Beckettian lineage). The threat of the po-po (the police) always has the pair on high alert. “Yo kill me now!” shouts Moses when he wakes up from a night of uneasy sleep. “Bang bang,” replies Kitch. And so begins another day for the pair, who spend their hours cracking jokes and dreaming about finding a Promised Land where the food is plentiful, material wealth comes easy, and the cops are nowhere to be found.

(© Joan Marcus)

Into their streetlight world ambles Mister, a white man (Ebert again) dressed nattily in a light-colored suit and wearing a baseball cap and shiny white Nike high-tops (costume design by Sarafina Busch). Mister claims he’s gotten lost on the way to his mother’s house, but since he’s in the neighborhood, he offers to share the cornucopia of his picnic basket. Moses senses there’s something up with this white man, whose gee-gollies and by-goshes seem suspicious, but Kitch is eager to eat and quickly makes nice with this bearer of plenty. Mister’s super-polite veneer cracks wide open though when, in a provocative discussion of the N-word, he reveals that his real name is Master and exclaims, “Everything’s mine!” — including that word.

Ossifer agrees, as we later hear him casually spew the word when he subjects the men to humiliating frisks of a violent and vaguely sexual nature. Sound designer Justin Ellington and lighting designer Marcus Doshi give these scenes a terrifying feel: a rumbling bass note ripples through the air while a stark incriminating white light shines on Moses and Kitch. We’re meant to feel afraid for them, and we do.

The extraordinary thing about this production is that, despite the threat of violence that hangs over its two main characters, Taymor and her cast have dug into the play’s abundant comedy this time around. Nwandu’s language bubbles over with joy and humor throughout many of the scenes. Also, Smallwood and Hill (who originated the role of Moses at Steppenwolf) have deepened their performances since the Lincoln Center run. To watch them work together is a joy in itself.

There are moments that feel a bit awkward, particularly when Moses, a reluctant prophet, finally embraces his role as the one who can lead Kitch and himself into the Promised Land through a supernatural intervention. It’s here that the play diverts from its absurdist roots and makes use of a deus ex machina that strips Ossifer, literally, of his ability to harm anyone again. It will take more than that to get rid of the Ossifers of the world. After all, it took 10 plagues to change the mind of Pharaoh.

But perhaps to look at the play literally for an answer to police violence and to America’s deeply racist past and present is to miss the point. Pass Over itself — and the changes it has undergone — symbolize the kind of evolution that’s necessary for people to open their eyes and see what they couldn’t or didn’t want to see before. America’s Promised Land is here, the play tells us, it’s been here all along — but we don’t yet know how to see it. That’s an ending we still haven’t written.

(© Joan Marcus)