People for (or Against) the People's Opera (Part II)

Operatic death and what comes after.

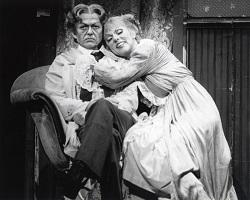

(© Carol Rosegg)

This is part II of Michael Feingold's latest "Thinking About Theater" column.

Click here to read part I.

Though many people trace the beginnings of New York City Opera’s downfall to its 1966 move from New York City Center to a new home at Lincoln Center (in what was then called the New York State Theater), the events that led to NYCO’s filing for bankruptcy last month actually occurred far more recently. As a surprising recent article by James B. Stewart revealed in The New York Times, the cold fiscal facts had little to do with either the company’s artistic profile or the “business model” on which it was run, although both could be said to have helped grease the company’s steep downslide. Ultimately, the cause was sheer, and shocking, monetary mismanagement, under former board chairman Susan L. Baker’s aegis: Beginning in 2008, the company’s substantial endowment ($51 million as recently as 2001) was simply thrown overboard in a series of panicky gestures that actively shriveled both NYCO’s producing presence and its financial stability.

Raids on a nonprofit institution’s endowment, as Stewart points out, can only be made after clearing a series of legal hurdles. The mayor’s office, the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs, and an assistant to the state’s Attorney General all signed off on the deal — though the last of those, at least, saw fit to attach to her approval a list of stringent restrictions (apparently not all heeded by the board). Under this less than vigilant custodianship, City Opera rolled rapidly downhill to its inglorious mid-season termination.

Others will investigate the fiscal and legal thornbushes into which NYCO’s managers so eagerly threw themselves. What puzzles me most is why nobody stopped them — and why the board members, supposedly expert in financial matters, never stopped themselves. My tentative answer: Everyone involved had forgotten what City Opera was supposed to be. Frantically trying to preserve what they perceived as the company’s world-class mission to outrank the Met in innovation, the board overlooked what had made ordinary New Yorkers love and attend City Opera. Fostering the misconceived notion of NYCO as a cutting-edge, high-art house, their efforts made their governmental overseers, overburdened and distracted, view the company as only a second-rank Met wannabe, hence dispensable. The City Opera’s actual identity was left behind, with no one to speak up for it.

This failure came out most clearly in Baker’s misguided desire to make Gerard Mortier, former provocateur-in-chief of the Paris Opera and then of the Salzburg Festival, NYCO’s new artistic director. Almost no one — except, apparently, Baker and the board — thought Mortier a viable choice. Unlike every previous head of City Opera, he was not American by either birth or adoption; he had never, in his career, expressed any particular feeling for New York or for the evolving urban-American culture that City Opera had embodied. His experience in enlivening heavily state-subsidized European institutions with shock-effect productions that played off a high-culture public’s long familiarity with standard works was exactly the opposite of the populist approach that had been City Opera’s mission from birth: opera against elite conventionality instead of opera for everybody.

Even so, Mortier’s plans — which included the New York premiere of Messiaen’s St. Francis of Assisi and Philip Glass’ new Walt Disney opera, The Perfect American — had precedents in NYCO’s history. But they never came to fruition: His accession collided with the budget crisis that trashed NYCO’s endowment. In the budgetary shambles following his withdrawal, the board appointed George Steel, whose taste and experience lay far from any operatic tradition. Steel’s previous post, as a creator of a contemporary-music series for Columbia University’s Miller Theatre, had focused on discrete, mainly small-format events with only glancing connections to music theater. Under his aegis, the now economically crippled company offered pathetic “seasons” that looked less like a repertoire than a tasting menu, divesting itself of its Lincoln Center home, its music director, its chorus and orchestra, and its accumulated sets and costumes; Hurricane Sandy wrecked much of NYCO’s archive. At the end, no donors stepped forward to rescue it; there was hardly anything except memories left to rescue.

What remains, though, is the need — or rather, the many needs: the New York public’s need for inexpensive, accessible opera; our countless young artists’ need for a testing ground before a tough, lively audience; our arts community’s need for a company flexible enough to take daringly old-fashioned risks along with those deemed cutting-edge or intellectually chic. As NYCO shriveled, dozens of tiny companies seemingly sprang up to offer at least a partial fulfillment of those needs. My calendar as I write this includes Amore Opera’s U.S. premiere of Winter’s Das Labyrinth (a 1798 sequel to Mozart’s Magic Flute) and Gotham Chamber Opera’s re-creation of the 1927 Baden Baden bill of one-acts that premiered Weill’s Mahagonny Songspiel, his first collaboration with Brecht.

Many such companies now thrive here. Though all welcome, none can singly fill the place City Opera held for six-plus decades. If someone could find a moderate-sized space where a half-dozen of these companies might work in rotation, sharing an orchestra and a chorus, something opera company-ish might develop. Or, if some public-spirited entrepreneur, who shared the foresight that created New York City Center out of the derelict Mecca Temple in 1943, would come forward, something resembling a municipal opera might be reborn.

Such an entrepreneur would need to be fearless. He or she would have to be willing to face down a city full of fashion-chasers, deconstruction-drunk Europhiles, and pedants spouting everything from postmodern theory to original-practices dogma. Our entrepreneur would have to brave their mockery while firmly asserting that terms like “low-priced tickets,” “opera in English,” “popular favorite,” “easily followed narrative,” and even “Gian-Carlo Menotti” are not dirty words. Fearlessness would indeed be required.

But then, fearlessness was needed on February 21, 1944, when Laszlo Halasz stepped into the pit to conduct the company’s first performance (Tosca, with Dusolina Giannini). It was needed a year later when Camilla Williams, singing Cio-Cio San in Madama Butterfly, became the first African-American woman to join the roster of an American opera company. It was needed in 1949 when the company unveiled its first world premiere, William Grant Still’s Troubled Island, libretto by Langston Hughes. Opera always needs fearlessness.

So who will be fearless? Who will hire the young singers and players fresh out of the conservatories, the young directors and designers cutting their teeth off-Broadway and longing for operatic splendors? Who will build, on a spine of Tosca-Traviata-Carmen, the worlds of Kurka’s Good Soldier Schweik, and Hoiby’s A Month in the Country, mingled with Mozart and Messiaen, Handel and Henze, Glass and Ginastera? The Met does some things in this vein — several of which it learned about from their City Opera premieres. But the Met has other aspects of operatic life to maintain; it cannot do everything. The small companies, working on their intimate scale, are likewise limited.

The company we want, being municipal, will resemble New York: plainspoken, multiethnic, offhand, friendly; alert rather than hip; straightforward and funny rather than haughty and pretentious; a little dowdy in its homespun but happy to ignore the shrieking whirlwinds of chic. That sounds like a portrait of a person, not an institution: That sense of personhood, lost sight of in NYCO’s last flailing years, is precisely what this city’s next major opera company will need to create.

(© Richard Termine)

Michael Feingold's next two-part "Thinking About Theater" column will appear on consecutive Fridays November 15 and November 22.