(© Monique Carboni)

I was on my way to a matinee when I learned the horrible news. At the theater, nobody spoke it out loud — the occasion was a very special one that nobody wanted to spoil — but you could hear the muted murmurs all over the house before the show, and all over the lobby at intermission, as smartphones got checked and the technologically equipped kept their friends informed. "Philip Seymour—" "He what?" "No— that can’t be." "He couldn’t—" "Oh, my God— how awful." Philip Seymour Hoffman, age 46, had been found dead that morning, in his office/apartment on Bethune Street, under conditions that suggested a self-administered heroin overdose. Waves of shock, despair, and devastating grief were breaking over the nation at large, and cresting higher as they broke over the New York theater community, where Hoffman had been not only a leading figure but an approachable one: a friend, colleague, and mentor to many; an idol and role model to a host of young aspirants. His loss, and the sordid pain of its circumstances, sent the public consciousness reeling.

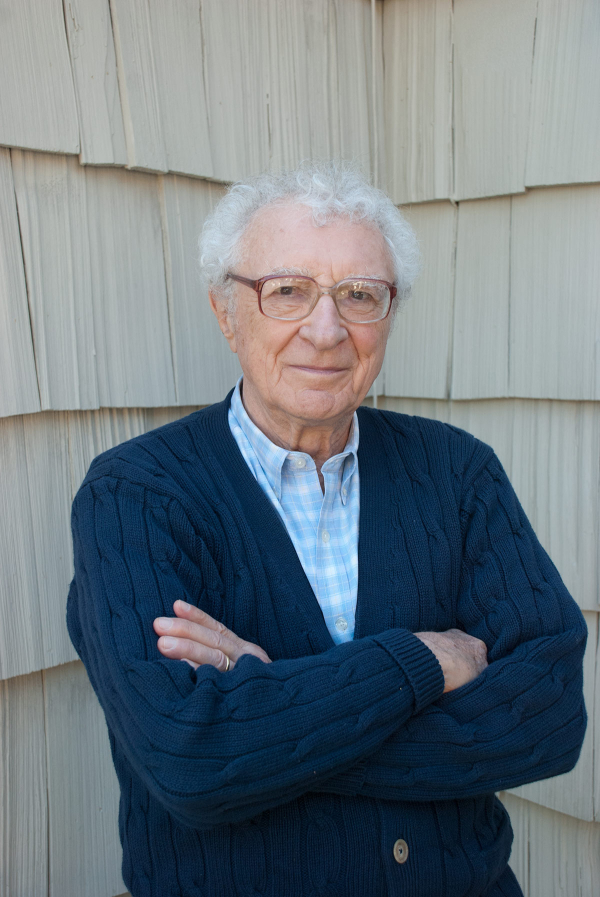

And the matinee I was attending was a kind of rebuke, or counterblast, to the very idea of an artist dying, so young and so relatively unfulfilled, in such ghastly circumstances. It was a staged concert, the second in the York Theatre Company’s annual "Musicals in Mufti" series, which is devoted this year to honoring the wonderful songwriter Sheldon Harnick. And Harnick — a man nearly twice Hoffman’s age — was very much present: hale, hearty, alert, as genial and as wittily articulate as ever.

(photo courtesy of York Theatre Company)

The series is exploring Harnick’s less-known and less-produced shows, and that weekend’s occasion was New York’s first public encounter with Dragons, a project that had stayed close to Harnick’s heart for five decades — he wrote its music as well as its book and lyrics — while finding its way onstage only in a few scattered college productions over the years. And his fine-tuning of it was ongoing: The York’s Mufti staging included a just-written new song — an eleven-o’clock number, unexpectedly given not to the hero or heroine, but to a subordinate villain. And the song, sharp and poignant in the best Harnick manner, proved to be delightful as well as painfully apt.

It carried an eerie aptness, too, to the gloomy news that hung over everyone’s awareness as we watched Harnick’s sardonic parable play itself out. Dragons is not about drug addiction and does not, except in the most peripheral way, deal with the challenges that face artists, but like many parables, it addresses general human problems in terms that can be applied to a wide variety of situations. I don’t know if anyone else present connected what they were seeing to what had happened so tragically to Hoffman, but for me the link was glaringly, tormentingly obvious.

Dragons is based on a play by the Soviet-era Russian writer Eugene Schwartz (whose name is sometimes transliterated as Yevgeny Shvarts). Harnick discovered the play, which is simply titled The Dragon, the same way I did: at a 1963 production drolly staged by Joseph Anthony for the old Phoenix Theatre, down on Second Avenue and 12th Street.

Schwartz was a dual-capacity writer who survived the nightmarish pressures of the Stalinist era by working in low-key genres less subject to the ideological censors’ scrutiny. A specialist in children’s literature, he edited a magazine for kids. His stories and plays (he wrote about 25 of the latter) were mostly aimed at child audiences, and often dealt in familiar fairy-tale motifs. In a few of them, of which The Dragon written in 1944 is the most notable, he smuggled adult political parables, replete with wry ironies, into what look like, on superficial inspection, old stories retold in a breezier modern manner.

In The Dragon, as in the musical Harnick has shaped from it, the hero, Lancelot, is a combination of earnest medieval knight-errant and slightly puzzled contemporary misfit. Arriving in a town that’s been ruled for ages by a terrifying three-headed dragon, he meets and falls instantly in love with Elsa, a pretty girl whom the town has chosen as this year’s virgin sacrifice to the dragon. Vowing to save her, Lancelot challenges the giant creature. The subsequent action tells how some of the townsfolk help him, others hinder him (for reasons that Schwartz paints mordantly), and how he finally slays the beast, but with scant reward for either himself or the town.

Manifestly, the three-headed dragon, keeping tabs on the behavior of everybody in town, stands in for the Stalin-era USSR; Soviet censors weren’t fooled when Schwartz and his director tried to dodge that suspicion by claiming it was really an image of Hitler, whose armies Russia was battling at the time. They shut the original production down after one performance; an attempt to revive it in the year of Schwartz’s death met a similar fate: The "thaw" had made it okay to criticize Stalin himself, but the system was still the system, not to be messed with by spinners of smart-aleck fairy tales.

But there’s more to the work. As Harnick perceived, Schwartz’s twisty ironies give his play a remarkable multipurpose density for a seemingly transparent little political cartoon. The dragon’s monstrous demands are treated simply as a given; Schwartz’s emphasis is on the varied ways in which the townspeople adapt to his rule — or abet it for their own profit. Viewed from a range of vantage points, Lancelot sometimes seems as much a fly in the ointment as a savior. The idea that he has to drag the reluctant townsfolk to their half-undesired liberation offers wide and troubling implications. Here, as at many points during the performance, I couldn’t help thinking of Hoffman, imprisoned by an inner dragon that took his mind away from his home, his children, his work, his artistic ambitions, and the theater troupe that he had co-founded and nurtured. Schwartz’s original offered me no answer to the question of why this had happened. Harnick, who has wrestled with the play’s problematic ending, gave me, with his latest version, at least a clue. More about that next week.

(© Brigitte Lacombe)

Stay tuned to TheaterMania for part II of this "Thinking About Theater" column, which will appear on Friday, February 21.