Point-Counterpoint: Should Theaters Be Able to Lock Up Your Phone?

Our critics debate a new measure to curtail cellphone use in the theater.

(© Seth Walters)

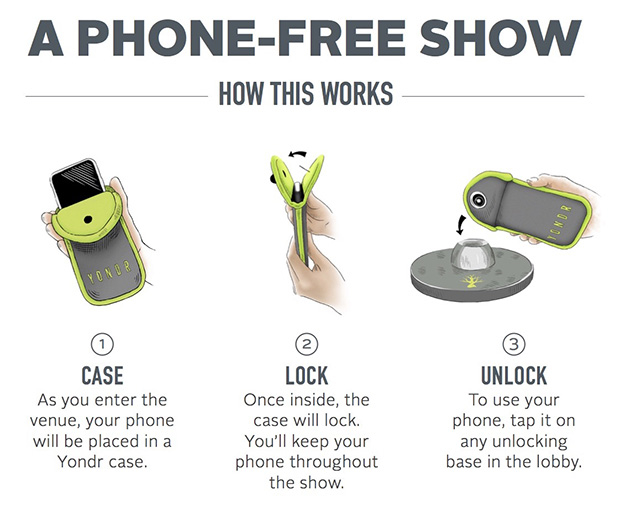

Almost everyone can agree that it's annoying when a phone rings in the theater, or when the glow of a screen illuminates a blackout — but what can be done about it? Some producers are taking drastic steps: In order to enter the theater for the recent off-Broadway run of Freestyle Love Supreme, theatergoers had to encase their cellphones in Yondr pouches, which were then sealed and could only be reopened by staff at the end of the show. While audience members kept possession of their smartphones for the duration of the performance, they were not able to use them. Some people hail this as an innovative way to protect intellectual property and the sanctity of the audience experience, while others see it as creeping authoritarianism in a traditionally free space. Our critics, Hayley Levitt and Zachary Stewart, weigh both sides of the debate in their latest Point-Counterpoint:

Hayley Levitt: Zach — this past winter, Freestyle Love Supreme introduced the world of off-Broadway to the policy of cellphone jail. Is that smart strategizing or a violation of the American freedom to Internet access?

Zachary Stewart: As someone who is regularly disturbed by the sound of a cellphone ringing in a theater, I understand how an individual's choice to not shut off their phone impacts other people's enjoyment of a show. Still, I bristle at the notion that attending the theater should resemble entering a federal courthouse. We already have increased security screening at many theaters, with guards rifling through our bags; do we really need to be forced to turn off and lock away our phones too? If the theater is going to remain a welcoming space for free people engaged in free thought, we shouldn't impose these coercive barriers to entry — even if that means that cellphones will occasionally disturb the performance.

Hayley: I'm usually the one advocating for fewer barriers and more inclusivity (wear your flip-flops to the theater, who cares!). But in this case, I'm willing to sacrifice a little personal freedom for the sake of the battle against cellphones. If audiences continually ignore instructions to put their phones away during a show, I think it's totally within the theater's right to find a way to eliminate that problem. It's a policy that doesn't decrease accessibility, and in no way discriminates against any particular subset (other than rude people). All it does is dictate behavior once you're inside, and I say: Not your house, not your rules.

Zach: Even if I don't agree with it, I can understand the implementation of the Yondr pouch in settings where cellphone use is common, like concerts and comedy shows (both Donald Glover and Dave Chappelle have used them). The artist is asking for a radical cultural shift, and that requires new tools. But the taboo against cellphones in the theater is already well established. Audiences know to shut off their phones. When they ring, they know they've made a mistake and usually rush to correct it. I go to the theater almost every night, and I haven't noticed an uptick in people completely violating that understanding. At least in the context of off-Broadway, the Yondr pouch really feels like an onerous solution to a negligible problem.

(© Joan Marcus)

Hayley: The cellphone problem has moved beyond people just forgetting to turn off their ringers or alarms. The bigger issue at this point is the compulsion to use your phone in the middle of a show. A friend of mine witnessed Patti LuPone terrorize a texter at Lincoln Center back in 2015. And another friend observed an audience member watch an entire basketball game during a performance of War Paint (I guess they follow Patti). The availability of other forms of entertainment and stimulation in a situation when you're supposed to be totally present (not to mention aware of the people around you) sucks the energy out of a room and diminishes the experience. Shutting that down altogether can only be a good thing.

Zach: As a society, we already have a perfectly good tool to combat such behavior: shame. If you've ever attended a matinee at one of New York's many not-for-profit theaters, you know that the negative response to a phone ringing in the show often drowns out the sound of the phone itself. Certainly, you wouldn't get away with texting in the middle of a performance very long without being told off by a fellow theatergoer, or asked to leave by an usher.

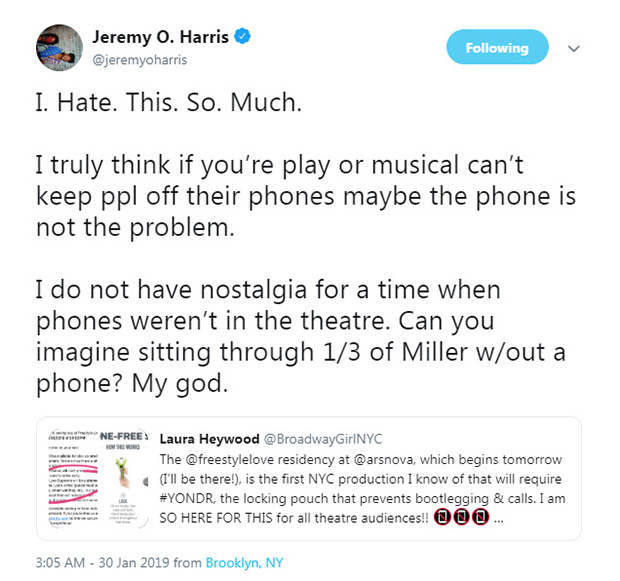

Hayley: You would think shame would be enough! But then I saw this tweet from Jeremy O. Harris, who, for people who haven't experienced his work yet, is an incredibly talented playwright who made his New York debut earlier this season with Slave Play at New York Theatre Workshop, which was quickly followed by Daddy (starring Alan Cumming) with New Group.

Ostracism is powerful, but if you have respected playwrights in the community teaching audiences that it's the play's job to keep them entertained enough to put their cellphones away, I think we're headed for a backslide. I'm all for looser boundaries in theater culture, but this isn't a tech startup — audiences aren't owed a foosball table and a beanbag chair when they buy a ticket to a show.

Zach: Unless it's an immersive play about the whimsically Orwellian culture of tech startups! While I'm not sure Mr. Harris's tweet (and its three retweets) will unleash the deluge of rude cellphone behavior, I can understand the impulse to stop it before it starts — just like I can understand the impulse to build a wall on our southern border to prevent illegal crossings. But is a wall really worth the cost of construction, or the impact it would have on America's image as a free and open society? The Yondr pouch is the theater's own version of Trump's wall — and we should be mindful of the unwelcoming message it sends before we decide to build it.

Hayley: Oh wow you brought the Wall into this! That's a terrifying way to frame a pretty innocuous contraption. I don't see it as such an unwelcoming addition to the theatergoing experience that people will start boycotting live events in demonstration of their right to open cellphone borders. And let's keep in mind we're talking about the span of maybe two hours — not perpetuity. I've had a piece of Junior's cheesecake confiscated from me at a theater. Yes, it was very sad, but I got it back at the end of the show and moved on with my life.

(© Matthew Murphy)

Zach: The fundamental breach of basic American freedoms aside, I have a technical concern about the Yondr pouch: When I attended Freestyle Love Supreme, the staff asked several times if my phone was off (or on silent mode) before sealing it up. But usually, when someone's phone goes off in the theater it's because they didn't realize it was still on, or they had set an alarm that ignores whatever "silent" mode they have. Essentially, it's user error. People are pretty good at making the ringing stop once it starts, but how would they do that when their phone is mummified and cannot be unwrapped without the help of a staff member? This technology could actually exacerbate the problem.

Hayley: That's a very valid concern. And it leads me to believe the primary problem the Yondr pouch is trying to solve isn't the ringing, but mid-performance recording — which opens up a much bigger and emotionally fraught conversation about bootlegs. I have seen more Instagram arguments about the ethics of Broadway bootlegs over the past year than I can count.

Zach: I'm sympathetic to the concerns of artists who want to be able to perform live without their performance being preserved forever on the Internet (where they can't even make any money off of it). But I think that topic merits its own debate. Same time, same place?

Hayley: Till next time…